When, in July 2017, British Labour peer Andrew Adonis hit out on Twitter at academics’ supposedly light teaching load and “sacrosanct” “three-month summer holiday”, he might have expected little response from a profession dozing off behind its collective sunglasses.

“Truth is, every job I have done since being a uni lecturer was FAR more demanding in terms of requirements to ‘do’ and ‘produce’,” blasted the former Cabinet minister, who was a fellow at the University of Oxford in the late 1980s.

Instead, however, the pushback was rapid and vigorous. Many academics made the point that summer is the only time during the year that they are able to focus on the research that is supposed to account for two-fifths of their working lives, according to the standard 40/40/20 contractual split between research, teaching and administration.

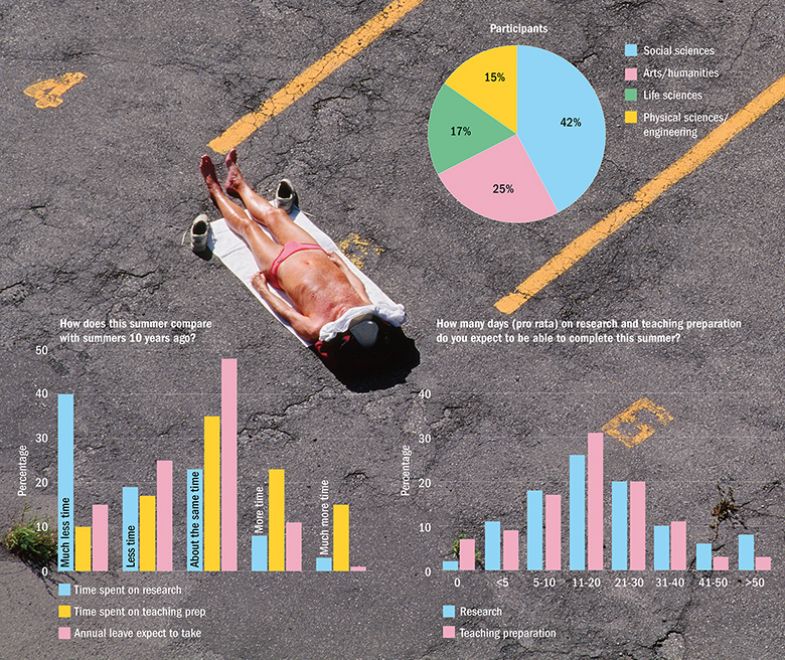

Yet even summer is not without its competing obligations to those other occupational categories. While there are about 65 working days in July, August and September, most academics expect to be able to devote less than half of that to research. Of nearly 200 respondents to an online Times Higher Education straw poll carried out in May, 77 per cent expect to be able to complete 30 days or fewer over the current summer (or, in the case of academics in the southern hemisphere, in the summer beginning in December). And 31 per cent expect to spend 10 days or fewer.

Of the 189 respondents – 68 per cent of whom are from the arts, humanities or social sciences, and 78 per cent of whom are from the UK, with 12 per cent from the US – just 11 per cent say this is more time than they had during summers 10 years ago (or since they began their career), compared with 59 per cent who say it is less.

Summer or not, the demands of being head of department “never end” for one UK-based arts and humanities academic: “Hiring goes on right through the summer, with ongoing frustrations. If I’m lucky I’ll get two weeks or so – probably not in a block and only by posting ‘go away’ email bouncebacks – to engage my brain with the large research project that I am principal investigator for.”

Meanwhile, a UK-based lecturer and programme leader in social science will try to devote July to research. But “professional services staff still need things from us over the summer as they don’t have the same cycle as us. I’ll have two weeks of leave in August, then another two weeks to write/research. But I still have MA and PhD students who require supervision…My deputy programme leader and I are planning a ‘tag team’ approach so we can switch off for a fortnight while the other person is ‘on call’.”

The lecturer adds that part of the reason for growing summer workloads is “the greater accountability and need to show how we are acting on student feedback”. But the lack of research time has career consequences: “I went for senior promotions last year and was rejected because I didn't have enough research money to my name, despite the amount of leadership activity I do in my teaching, and for ‘institutional citizenship’.”

Of the survey respondents, 68 per cent expect to spend at least 11 days on teaching preparation during the summer, and 37 per cent expect to spend at least 20 days. Compared with summers 10 years ago, 38 per cent of respondents say this is more time, while 27 per cent say it is less.

“Module handbooks need writing, online resources need preparing, there’s reading to do so that the modules keep up to date,” says a UK-based senior lecturer in the arts and humanities. “Then there’s work done on library resources, not to mention support for students with learning differences and disabilities, which has largely been made an additional responsibility of lecturers following cuts in support services.”

In the US, academics on 12-month contracts are able to “spend a lot of time during the summer” on research, according to Kathleen Fitzpatrick, director of digital humanities and professor of English at Michigan State University. But the large number of adjunct faculty on nine-month contracts are often obliged to work in summer schools or elsewhere “to pay the rent or buy the groceries during the summer”, Fitzpatrick adds. This cuts into the time they have for research, and any time they do find is off contract, so is in effect unpaid labour.

Even some tenured staff find themselves in this predicament. A US-based assistant professor in English tells the THE survey that she earns less “than the local K-12 teacher. I have to teach three summer school courses just to make ends meet. I’m not sure how much time that will give me [for research]. I’m hoping for seven days.”

Summer is a particularly important time for Australian researchers, according to Hannah Forsyth, a senior lecturer in history at the Australian Catholic University, since many need to travel overseas for it. But while that is still possible at some institutions, at others, “administrative time is creeping into that – and, of course, applying for grants is now eating into actual research”.

The challenges of finding time for research

Summer, of course, is also supposed to be about taking a holiday. But our survey suggests that this, too, is feeling the squeeze. While 96 per cent of respondents expect to take some annual leave this summer, 19 per cent will take only up to a week, and another 32 per cent up to two weeks. For 40 per cent of respondents, this is less time than they took off 10 years ago, compared with 22 per cent for whom it is more.

The summer demands of master’s teaching, resit marking and preparation for the new term leaves one UK-based social sciences lecturer facing a “choice between annual leave or research”. And a UK-based arts and humanities lecturer says that “taking too much holiday feels like career self-sabotage” and “letting down” their department in the research excellence framework.

“I haven’t managed to take my full holiday entitlement for much of the last 5+ years,” laments a UK-based senior lecturer in the life sciences. “The necessity of admissions has meant there are not enough days where I can take a holiday. So, this year, I will lose 5-10 days of unused annual leave AGAIN!” And a UK-based senior lecturer in the physical sciences only managed to take half of their allotted annual leave last year: “The volume of work in supporting teaching, supporting admin, doing admin that admin should really be doing, supporting students/staff and doing student recruitment activities leaves little to no time to even contemplate holiday or research.”

Even when academics do take time off, they do not necessarily turn off their computers. A social sciences associate professor in Australia notes that the Christmas shutdown in early summer obliges academics to take annual leave then even if they are still working. Meanwhile, a UK-based creative writing academic notes that “my annual holiday is my research time – if I am to get half a book written, it is the only way. I’m not taking an actual vacation other than a couple of long weekends.” And while a UK-based lecturer in the physical sciences expects to take up to three weeks of annual leave this summer, they will still be answering emails since “as an academic, most of the things I am responsible for are one person deep: there’s no one else to name on an out-of-office response”.

Lynn Kamerlin, professor of structural biology at Uppsala University in Sweden, has also used leave for research time and can “probably count on two hands the number of days off” she has had in the past year. “No one will ever call me a slacker, and I push myself really hard – but there is only so hard you can push yourself before you collapse,” she admits.

On the other hand, Jenny Pickerill, professor of environmental geography at the University of Sheffield, has never used her annual leave for research and finds the trend “really worrying” because “it utterly defeats the object of having annual leave…Most of us have never taken our full quota anyway…I think we need to make the problem [of excessive workloads] visible, not hide it in our annual leave and working from home.”

Working during annual leave is not just confined to academia. James Richards, an associate professor in human resource management at Heriot-Watt University, is carrying out a survey on what is known as “leaveism”: the “largely invisible, unmeasured and under-appreciated work that is done during annual leave, when ill or on maternity/paternity leave, and/or excessive use of evenings and weekends to do work/catch up on work”.

But the survey has struck a particular chord with academics, says Richards. He cites one respondent who wrote virtually an entire book while on maternity leave since it was the only opportunity she was likely to get to do so. “A key issue is that [leaveism] is becoming expected or made mandatory by employers, rather than being volunteered by engaged professional and salaried employees,” he says.

Less time for research but more time on work

Many survey respondents see the difficulty of carving out research time even during the summer as symptomatic of a general rise in academic workload. A UK-based physical sciences professor puts it this way: “The only thing that stops over the summer period is direct undergraduate teaching. Everything else continues at the same level, and since term-time workloads are already far more than 100 per cent of a standard working week (35 hours), that still doesn’t leave much time for research.”

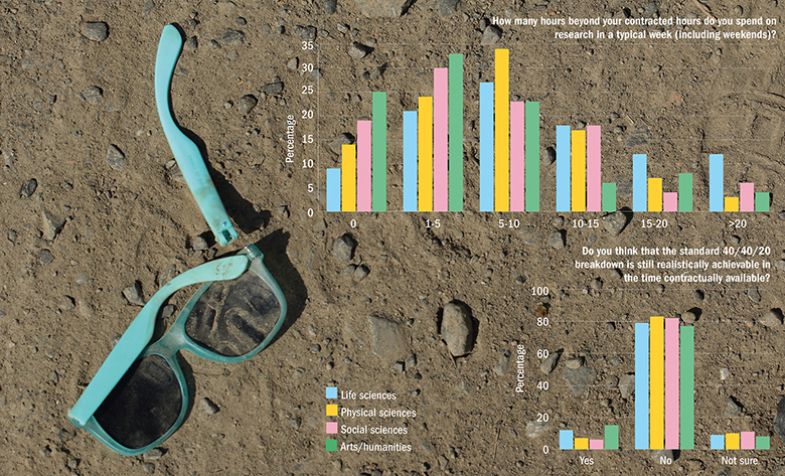

While 51 per cent of survey respondents are expected to spend 40 per cent or more of their contracted hours on research, 65 per cent estimate that, in reality, they manage less than 20 per cent; 67 per cent say this is less than 10 years ago, compared with just 8 per cent who say it is more.

Many respondents, therefore, find themselves working during their own time. Some 54 per cent spend up to 10 hours beyond their contracted hours on research in a typical week.

“Term time is so fragmented, with two- or three-hour teaching blocks, plus one- to two-hour meetings, tutorials and the ludicrous explosion of email (I routinely have 2,000-5,000+ unread emails waiting for me to have time to get to them),” laments a UK-based senior lecturer in the life sciences. “All this means it is almost impossible to find blocks of time to do experiments, write papers, research and catch up with the relevant literature in the field, write grants or just THINK and, hence, have ideas for the breakthrough or next project.”

Meanwhile, a UK-based social science professor notes that “bar one week in May (albeit, taken as holiday leave), I haven’t had any time for research during the teaching year at all, despite working at a so-called research-intensive university. This is now the norm for many of us.”

It is by no means only research that sees people working early in the morning, late at night or at weekends. Slightly higher proportions of respondents – 55 per cent in both cases – spend up to 10 additional hours a week on teaching and/or administration. Time taken for the latter is “grossly underestimated” in workload models, according to a UK principal lecturer in the physical sciences. “Forms have just taken over my life,” despairs a UK social sciences lecturer.

Many respondents blame this administrative overload for their inability to fulfil their contractual obligations regarding research: “I have basically just given up and accepted that my research and grant writing are things that happen on evenings and weekends,” says Uppsala’s Kamerlin.

A former classical musician, she recognises that academia shares the performing arts’ problem of hyper-competition: “So many people would give their right arm for your job, so academics feel like they can’t really speak up,” she says. This leads to a “vicious cycle” whereby management expect “more and more” from academics, who “just do it”, leading to burnout and lack of productivity.

While 39 per cent of those surveyed by THE say that the 40/40/20 workload model is still the ideal breakdown, compared with 38 per cent who do not, a massive 80 per cent say it is not realistically achievable in the time contractually available. Just 10 per cent take the opposite view.

A UK senior lecturer in the physical sciences says it is only realistic “if the 20 is research”, while Michigan State’s Fitzpatrick regards 40/40/20 as a “great ideal division of labour”, but when it requires “120 hours a week to do that work, it’s not appropriate”.

The time for research is being squeezed

Academic workload reaches its crescendo during the marking season that immediately precedes the summer break. Last year, the UK sector was rocked by the nationally reported suicide of Malcolm Anderson, a Cardiff University accountancy lecturer, who had been asked to mark 418 exam papers in 20 days. And, this year, Sheffield’s Pickerill found herself facing her own dark night of the soul.

“I am sitting in my office at 7pm crying,” she tweeted in early June. “I am surrounded by piles of marking I need to moderate tonight. I have worked solidly for the last 10 days, often 12 hour days. I am utterly overwhelmed + exhausted. This is the life of a British academic.” She was ultimately persuaded by other Twitter users that she didn’t have to comply with the bureaucratic demands that were “pushing me to the edge”. Instead, she sent her university a note stating that “having marked 150 scripts in just a few days I do not have the time, capacity or energy to complete the required six separate forms to individually moderate each question marked by a different marker”.

But Pickerill’s predicament was far from an isolated one, and nor is the stress of overwork confined to exam time. A May paper by Liz Morrish for the UK’s Higher Education Policy Institute revealed that 41 per cent of respondents to a survey self-declared that their workload negatively affects their mental well-being.

The problem, according to Pickerill, is that while teaching and administrative expectations have grown, the time allocated to them has stayed the same. She is “pragmatic” enough to recognise that most of her department’s funding comes from undergraduate teaching, “so we can’t squeeze the time we spend on teaching and making the department function without becoming financially unsustainable”.

Hence, the expectation that academics have two days a week to focus on research is “just not true”. If people want to do a “really big piece of research”, the only way to do it, Pickerill says, is to buy out their time by winning a grant – which is getting “harder and harder” to do.

Academics in the US can also get their teaching load lowered “by getting out there and hustling to get their own finance”, says Darren Linvill, associate professor in the department of communication at Clemson University. But he sees this as “a strange system. I think if we took all the money and time and resources we spent trying to get money and reallocated that we might be better in the long run. The acceptance rates on grants…are just so low that a lot of that effort…is wasted.”

According to the American Association of University Professors’ policy on faculty workload, it is “very doubtful that a continuing effort in original inquiry can be maintained by a faculty member carrying a teaching load of more than nine hours [a week]”. It also notes that a number of leading research-intensives have “already moved or are now moving to a six-hour policy”. But, it cautions, such policies must be applied across the board, rather than to just a few elite researchers “if research is to be considered a general faculty responsibility”.

The Australian Catholic University’s Forsyth has, for the past three years, been in the “fortunate position” of being on a large research grant. But she remembers when, with a high teaching load and a looming book deadline, she had to start each day at 4.30 in the morning.

She says the problem is being exacerbated by Australia’s multiannual research audit, known as Excellence in Research for Australia. It has prompted universities to concentrate their research support into a smaller number of what they “perceive to be high-quality researchers”, leaving others with higher teaching loads. That is particularly true for the permanent staff who “carry a lot of the work [such as double-marking] that we don’t want casuals to do because they are not being paid to do it and it’s not fair”.

Forsyth fears the emergence of a “two-tier system of academics”, whose lower tier is “pushed ever more into very high teaching loads, which makes it impossible for them to do any research at all”.

A recent survey by Australia’s National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) showed that 81 per cent of scholars think they do not have time to do the amount of research they need to do. According to Nick Riemer, a senior lecturer in English and linguistics at the University of Sydney and a member of Sydney’s NTEU branch committee, universities trade on the fact that academics see their jobs as a vocation. They are “in it for love and are therefore willing to spend their own time on research”, he says. “There is some truth in that, I think, but it’s not a justification…for exploitative overwork.”

He describes the 40/40/20 model as an “administrative fiction” bearing no relation to the actual hours people work.

So are there any good strategies for creating more time for research?

One UK senior lecturer in social science says that, over the years, they have “stopped being collegiate” and working in their university office “as you just get given work. I make every effort to only be visible when absolutely necessary.”

Pickerill describes herself as “naturally an optimist, which is why I am still in British academia. I think the key thing for me is to assert my right to research time without pushing my work down to the more precarious or early career researchers.” Solutions could include spending less time on teaching preparation, devising assessments that require less arduous marking, and “really, really thinking about what admin we have to do and what we don’t”.

One way that Pickerill and her colleagues at Sheffield are “pushing back” is by running writing retreats during term time, in order to hold off the constant demands of teaching and administration. “What we are trying to do is to make writing visible and make it collective,” she says. Clemson’s Linvill agrees that “you have to guard” your research time. But “it’s not just [about] communicating that to other people: it’s also about communicating that to yourself. The longer I have been here the more important I realise it is to…communicate to my students when it’s appropriate to come by my office and to realise that it is OK for me to close my door sometimes.”

Fitzpatrick has her own methods for making research time, but she “would hesitate to recommend them to anyone other than me”. Most weekdays she works at home between 5am and 7am before going into work, and also spends most of her weekends and vacation on research. She does so “because I love it and, for me, it works. I don’t feel it interferes with other aspects of my life. But I don’t have children, and if I did it wouldn’t be viable at all.”

There are also fears that the quality of research will decline as the competing pressures mount. Fitzpatrick suspects that the shortage of time for research will only enhance the unfortunate trend for researchers to “salami-slice” their research into as many separate papers as possible. Important projects can take a long time, but if academics are “constantly having to demonstrate productivity” they are not going to be focused on the big picture, she warns. “Urgency takes the place of importance, always.”

Sydney’s Riemer is also concerned that the lack of time for research is a “recipe for a generation of bad work”. High-quality research in the humanities requires a “creative element”, which can come only when academics have a “certain degree of freedom from the grinding pressures of the rest of the job”, he says. “Ideas need time to breathe; I find that I have my best ideas, for example, when I am actually not working.”

At an institutional level, most survey respondents regard the most attractive solutions to overwork as cutting teaching and, especially, administration loads.

A UK social science lecturer suggests re-capping student numbers because “we are overrun”, while a senior lecturer in the social sciences suggests capping the “number of meetings any one member of staff can attend in a week, set sensible limits on emails [and] set reasonable expectations for students” in terms of staff contact. And a UK head of department in the social sciences puts it more succinctly: “Employ more staff. Period.”

Heriot-Watt’s Richards says university managers have “too much power”, leaving employees feeling that “they don’t have any kind of real means to respond to [excessive workload]”. And what efforts there have been to push back “have not been very successful. So I suppose trade unions have a role to play in this.”

Michigan State’s Fitzpatrick agrees that academics “really need to come together and, frankly, unionise” in order to conduct "collective bargaining with their institution to determine what the terms of their employment should be”. And Sydney’s Riemer sees “no prospect of any kind of natural improvement, except one that is actually fought for by staff, and staff collectively – ideally, I think, through the trade unions…For the purposes of securing and preserving the ability to conduct research in the medium to long term, it is really essential that there be collective organising on the part of academic staff to reset the balance in favour of academic decision-making, not administrative decision-making.”

A spokesman for the UK’s Universities and Colleges Employers’ Association (Ucea) says that universities are “very active in assisting colleagues in achieving work-life balance and manageable workloads right across an academic year. Where academics are on ‘teaching and research’ pathways, there is no single, static ‘blueprint’ for the balance of focus in their roles and, clearly, the balance of time between research and the other aspects of roles varies through careers and between and within academic years.”

For its part, the UK’s University and College Union has decided to launch its own major workload survey in the next academic year. Its incoming general secretary, Jo Grady, a senior lecturer in employment relations at the University of Sheffield, says that universities “benefit from our overwork: it’s quite simple. Some institutions are better than others, but the business model of universities is built on people working longer than they should, people working during leave…people working while they are sick, and people knowing that they have to do these things.”

In Australia, Forsyth is “not seeing management of any [Australian] universities” taking the issue of overwork seriously. Rather, it is dismissed as “just a lot of academics whining. The very serious problems of mental health and of workload are not being taken anything like as seriously as they should be.”

Pickerill, for her part, agrees that the Adonis-style “belittling that academics get – that we are just moaning and we have long summers” is not helpful.

“So the first step is to take us seriously,” she says. “And then we can start looking at better ways of managing workload. As long as we still have academics committing suicide over it then we are not doing enough.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Summertime, and the living ain’t easy

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login