“Never in the history of human scholarship has so much been written by so many to the benefit of so few.” Spoken by one of my co-authors at an academic conference in the social sciences, that Churchillian inversion drew spontaneous applause from an audience of around 400.

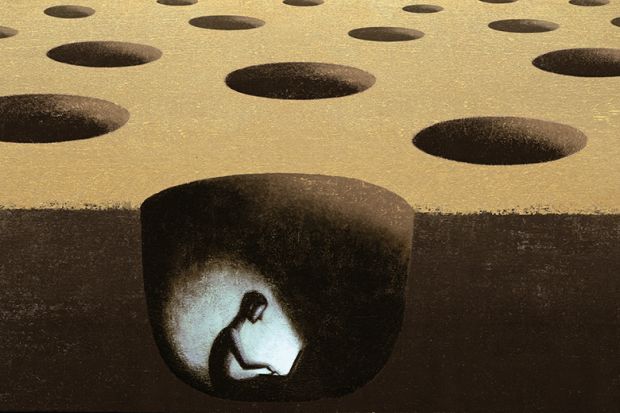

Academic publishing is now a game in which high performance forges careers and sustains departmental reputations hyped up on the back of publication and citation “hits”. It has become an unstoppable machine churning out texts. An estimated 50 million “scientific” articles are currently in circulation, increasing by more than 2 million each year.

It is no secret that, in the social sciences, most of these are jargon-ridden, formulaic and incomprehensible to anyone beyond tiny microtribes of subject experts. The vast majority have virtually no social relevance. Their only chance of catching the attention of anyone else is if some all-devouring algorithm throws them up in a literature search.

Materials that in the past would have been consigned to the filing cabinet of “juvenilia” are being published in respectable journals – which, themselves, proliferate by between 200 and 300 titles every year. Other articles, subjected to the rigours of anonymous review, are revised multiple times until they are virtually emptied of any originality or substance, while becoming engorged with references and other clutter.

Journal editors, university leaders, politicians and the majority of academics in the social sciences know this. Yet nearly everything they do contributes to feeding the machine.

There are certainly some winners in all this. There are the star academics whose salaries and privileges have risen to heights undreamed of by their predecessors even 15 years ago.

There are the publishers who have seen their profits soar on the back of unpaid academic labour.

There are the conference organisers laying on ever more workshops, symposia and meetings where papers can be presented.

There are the members of national committees and official bodies paid to concoct increasingly elaborate schemes for the evaluation of research “outputs”.

There are the cohorts of bureaucrats in every university making a living out of keeping score of publications and citations, manipulating the impact of papers and producing empty marketing verbiage extolling the supposed research excellence of their institutions.

And there are employers who appreciate having readily available rankings, however flawed, from which to choose prospective employees.

But the losers far outnumber the winners. These include the thousands of junior and adjunct academics working under unbearable pressures to attain the publishing “hits” that alone hold the promise – though not the guarantee – of more stable employment. They also include many established researchers, who discover that past successes count for naught in the next round of the game.

Then there are the students and taxpayers whose money is chewed up by the publishing machine for no social purpose, while those overworked and inexperienced adjuncts are left to do all the teaching.

Entire institutions find their contribution to education devalued by their inevitable failure to make an impact on research-based rankings. And the whole of society suffers because its most burning issues go unaddressed by social science researchers preoccupied with discovering tiny gaps in the literatures of their sub-specialisms and pretending to fill them, adding to the glut of nonsense that stops the few truly original and meaningful publications from being noticed, discussed and acted upon.

Competition – between individuals, institutions and even nations – has always been a feature of academic life. In the past, it drove many brilliant discoveries and added to the momentum for social reform. But research in the social sciences is no longer the serious vocation it once was. Getting a publication hit at virtually any cost is all that matters.

There is evidence that funding and professional bodies, as well as university leaders and even policymakers, are beginning to turn against this state of affairs. Accreditation bodies are showing some impatience with resources going to pointless research at the expense of teaching. In the UK, the teaching excellence framework is a belated if scarcely effective response to the recognition that teaching should be at the core of higher education policy. University applications are showing signs of decline as students are deterred by the high cost of sustaining pointless research activity via their tuition fees (as well as by the diminishing graduate premium), while the Labour Party’s popular pledge to abolish fees could cut off that cross-subsidy mechanism at the knees.

All of this calls for a major rethinking of the ways social research is funded, conducted and rewarded. For many years, academics have grumbled about the game they feel compelled to play, but they have done little to change its rules. It is now up to them – starting with editors, deans and senior scholars – to blow the whistle on the whole degrading spectacle.

It will take more than Churchillian rhetoric to repel the existential threat to social research. But any senior figure offering less than blood, toil, tears and sweat is complicit in serious crimes against humanity’s knowledge base.

Yiannis Gabriel is chair in organisational theory at the University of Bath. He is co-author of Return to Meaning: A Social Science that has Something to Say, recently published by Oxford University Press. Read a longer version of this article at www.yiannisgabriel.com.

后记

Print headline: Research in social science may well be doomed unless we act