Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2022 subject table for arts and humanities

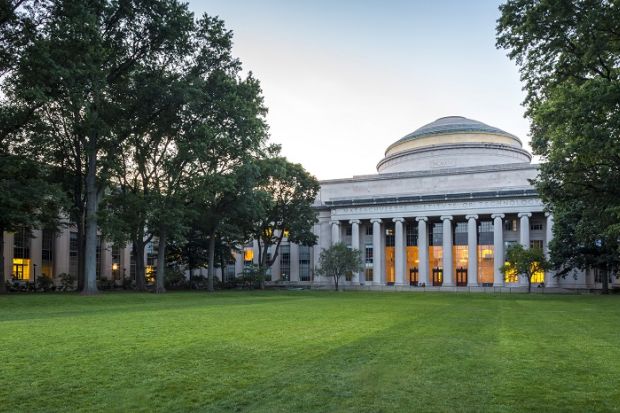

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s view on the significance of the humanities and arts for navigating the contemporary world and the era of advanced technology can be gauged from a single piece of data: 100 per cent of our undergraduate students study both the humanistic and arts fields.

At MIT, all undergraduates take a series of required classes, nearly a quarter of which are in the arts, humanities and social sciences. And many students go much deeper – majoring and earning degrees in architecture, design, history, languages, linguistics, literature, music, philosophy or theatre – often alongside a degree in a STEM field.

Graduate students also come to MIT for advanced degrees in disciplines including architecture, design, media, philosophy, linguistics, science writing, comparative media studies and multidisciplinary programs such as ACT (art, culture and technology), MAS (media arts and sciences), and HASTS (history, anthropology, and STS: science, technology and society).

The emphasis on the arts, design and humanities extends from education to research to arts programming and reflects the Institute’s view about the range of knowledge vital to advancing human and planetary well-being. The MIT mission is to serve humankind, and the arts and humanities are essential resources for knowledge and understanding of the human condition. The insights of science and engineering are, of course, crucial to addressing many of the world’s most urgent problems. But these fields operate within human societies, and can serve the world best when informed by the cultural, political, spatial and economic complexities of human existence, beliefs and ways of inhabiting the earth.

While the technical, scientific and humanistic research domains have distinctive qualities and methodologies, they are also mutually informing modes of human knowledge. And many of today’s most consequential issues will be solved only with collaborative research. Recognising the high stakes in this moment in human and planetary history, MIT’s community has increasingly embraced problem-solving approaches that can integrate sci/tech advances with humanities, arts, design and social science research, analysis and insight.

Relevant efforts at MIT that embody or contribute to such collaboration include work on: the ethics, societal responsibilities and potentials of advanced technology; the climate crisis; poverty alleviation; displaced people; social justice; health and healthcare; democracy and governance; misinformation; spatial storytelling; urban mobility; the global socio-cultural impact of architecture; and democratising media forms.

As the world grapples with these and related issues, it is encouraging to see leading voices in other STEM-centric communities also championing the impact of the humanistic fields. Notably, tech giant Google surveyed employees to identify the skills most important for success and found that the top seven are all rooted in humanities studies, among them critical thinking, communication, empathy (recognising the needs of diverse peoples) and making connections across complex ideas.

At MIT, we make the case that the humanities, arts and design disciplines develop key career and leadership skills in students, and have an essential research role in solving major civilisational problems. MIT historian/engineer David Mindell, for example, champions “dual competence” for students: “Master two fundamental ways of thinking about the world, one technical and one humanistic,” he writes. “Sometimes these two modes will be at odds with each other, which raises critical questions. Other times they will be synergistic and energising."

Similarly, MIT designer/computer scientist Skylar Tibbits, observes that “in design, we imagine things, we test things, we work collaboratively. Often there isn’t a right or wrong answer. This process attracts students who graduate as polymaths with skills they can apply to any field.”

Our science and engineering alumni provide some of the best testimony about the value of an education that develops fluency across the arts, design, humanities and STEM realms. An alum who majored in biology and theatre writes that “acting is a fundamental study of communication and empathy, which has been applicable to every aspect of my career and life”. An alum with degrees in engineering and architecture and a minor in visual arts describes his career as “a gumbo mix of technology startups and big agencies, where I’ve often functioned as a design and business hybrid”. An alum who is now a physician notes that her practice requires medical knowledge and the ability to interpret her patients’ narratives – something she learned studying the many ways humans share stories. She writes: “MIT biology prepared me for medicine. MIT literature prepared me to be a doctor.”

Equally important, however, we encourage students to delve into the arts, humanities and design fields regardless of the problem-solving applications or career benefits of such endeavours. We want them to think about the best way to live; to experience the agency of creativity; to gain an understanding of shared human history. It’s not only that research fuelled by abiding fascination has proved time and again to be valuable for the future in forms not easily anticipated. We also want our students to benefit from the ways the humanities and arts reliably contribute to well-being and a well-lived life. For their singular role in the gradual process of becoming our whole selves – discovering core values, a moral compass, creative powers, historical and cultural perspectives – the arts and humanities are rightly renowned. They are an essential part of an MIT education, critical to the Institute’s capacity for innovation and vital to its mission to make a better world.

Agustín Rayo is interim dean of the MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, and Hashim Sarkis is dean of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login