Browse the THE Asia University Rankings 2019 results

Having served for nearly three decades as a teacher, a researcher and a senior manager in British higher education, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity to return to the South Asian subcontinent to be part of an important educational project that is successfully addressing some of the key issues of quality, equity and access to higher education for women in the region. This initiative gives me hope that they are solvable problems.

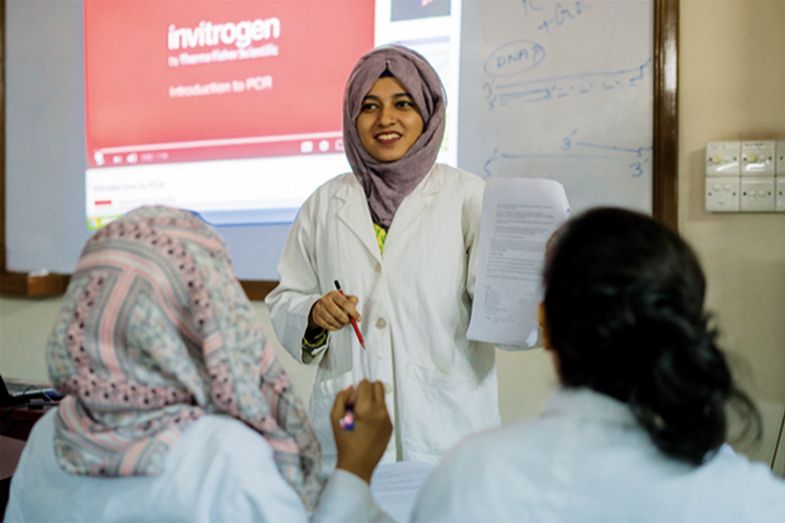

For the past two years, I have served as the vice-chancellor of the Asian University for Women, a liberal arts institution located in Chittagong, Bangladesh. It is the first of its kind – global in outlook but rooted in the contexts and aspirations of the people of Asia. The university has educated more than 1,500 women from 17 different countries, 35 ethnicities and five religions. Its central ethos is the idea that interaction with difference in the context of a liberal arts education can empower students to become empathetic, change-driving leaders in their communities and the world.

The South Asian subcontinent, although not homogeneous by any means, presents a starkly different context in many ways from the Western countries that have been at the centre of the dialogue on issues of equity and access. The challenges are many. From a young age, girls are expected to perform far more domestic chores than boys, including caring for younger siblings. Patriarchal structures frequently result in restrictions on women’s autonomy in general. Families are more likely to spend money on a son’s education than a daughter’s. Many girls are expected to marry and focus on raising children rather than enter the workforce or continue their education. Religious and social conservatism also limits women’s options, as families remain reluctant to send their daughters far away from home or to a co-educational institution for their studies.

AUW’s core objectives aim to relieve the persistent and inequitable issues of quality and access within higher education. Its primary goal is to recruit from underserved communities, such as displaced women and women from urban garment factories and rural mountain communities, and provide them with supplementary preparatory programmes. The university funds the majority of these women’s scholarship needs.

Equipped with diverse perspectives of a liberal arts education, about 75 per cent of AUW graduates return to their home countries to tackle the problems in their communities – and all are infused with the passion to create positive impact in the world. Likewise, by recruiting highly educated and international faculty, AUW promises a quality education that has proved competitive with other liberal arts universities in the US and Europe. The university does not compromise on quality when it comes to the instrumental power of education either: job-readiness and professional education are central to AUW’s academic choices and programming.

Every student at AUW has a story to tell and has demonstrated willingness to challenge those whose expectations keep her from cultivating her talents and expressing her pioneering spirit. Some have engaged in political activism by organising for workers’ rights while working in garment factories, or have fought for women’s rights in conflict zones. Others have displayed entrepreneurial imagination by finding novel ways to educate children while working within the limited resources of refugee camps. Some have escaped abusive child marriages and found the courage to stand up to their families. Others have been enterprising in their aspiration to give back to their communities, engaging non-governmental organisations and other foundations to invest in primary education, hygiene and other basic necessities. Still others have walked for days across Myanmar’s Rakhine state simply to get a chance to travel to AUW.

Each and every single AUW student has shown that she can find one or two sparks of hope that build resilience in the face of overwhelming odds. AUW aspires to show what these strong, resourceful women can do if given the means that many women around the world (especially in the West) already have and sometimes take for granted.

It is easy to suppose that cultural norms in certain parts of Asia combine with economic scarcity to reify conditions of gender inequality. AUW’s commitment to empowering women from across Asia has meant contending with the fact that sources of inequality in a pan-Asian context encompass a much broader array of factors than social, economic and political opportunity. The inequalities experienced by a Rohingya student – whose community has been denied access to higher education for generations, whose native tongue is not spoken in any institution of higher learning, and whose families have good reasons to mistrust outsiders – will have a very different set of challenges from an Afghan woman whose family might experience social repercussions for her choice to go to school. Although both come from conflict zones, share religious beliefs and have had only limited opportunities, they will face different challenges from each other and from those who arrive at AUW from Syria, Palestine or Yemen.

On the other hand, there are aspects of systemic injustice that AUW is positioned to challenge in a broad manner. Several secondary schools in Bangladesh and India prepare women to take jobs in garment factories, on tea estates or as microfinance borrowers. These are roads out of poverty but not ladders of social mobility. Once a woman gets a job, she is financially autonomous, but she can often expect menial wages and 10-hour workdays for decades of her life. Her secondary school qualifications have not built competencies to take up university places, even when scholarships are available.

AUW, therefore, created two pre-university bridging programmes to provide one more rung on the ladder of opportunity. Pathways for Promise and Access Academy give women opportunities to strengthen core competencies in English and mathematics, and then a chance to matriculate at AUW’s undergraduate programme.

Given the complexities of Asian inequality, AUW has tried to create a model flexible enough to accommodate the needs of students who have varying life circumstances but a common goal of overcoming the odds and staying true to their aspirations. By focusing on enterprising women who take leadership and social justice seriously, AUW is committed to creating the next generation of activists, entrepreneurs and change-makers who might be able to transform their lives in a way that has ripple effects across their communities.

Indeed, we see this occurring already as more students apply to AUW every year from communities from where successful alumnae have originated. We have also begun to see our alumnae use their education in ways that inspire change in their home countries. In the past year alone, one alumna was recognised by the US Department of State for her work with adolescent refugees; another from Cambodia was recognised as an emerging young Asian leader by the Obama Foundation; a third was recognised as a young film-maker for a documentary shedding light on children of sex workers in Bangladesh’s red-light districts; while several others have seized opportunities to attend graduate schools and pursue peace and conflict studies or research public policy and development.

However, like so many educational initiatives, AUW still faces the challenge of philanthropic support. Philanthropic attention seems to shift from year to year. What is declared to be of monumental importance this year fades in interest in the next. The university has demonstrated that it has built a model that works. However, without sustainable philanthropic support for some period of time, it cannot achieve its goals.

Nirmala Rao is vice-chancellor of the Asian University for Women.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login