When Times Higher Education surveyed leaders of prominent global universities in 2018, the 200 respondents – from 45 countries across six continents – were emphatic on one point: online higher education would never match the real thing.

Although 63 per cent expected established, prestigious universities to be offering full degrees online by 2030, only 24 per cent thought that the electronic versions would be more popular than traditional campus-based degrees (“How will technology reshape the university by 2030”, Features, 27 September 2018).

Lino Guzzella, president of ETH Zurich, asserted that “meeting people, interacting with peers, students and supervisors – in short, a real university environment – is the key to deep understanding”.

An Australian vice-chancellor said that “face-to-face interaction will never be matched in quality by other modes of communication” – even if current “fads temporarily appear to be tilting the balance towards non-human interaction”.

Jane Gatewood, vice-provost for global engagement at the University of Rochester in New York state, likened the difference between residential and online learning to the difference between visiting a new place and merely “watching a video” of it.

And Yang Hai Wen, vice-president of Southern Medical University in Guangzhou, China, said that online education would “create more unhealthy graduates and [create] more frustrations in interpersonal communication”.

Chinese social media is currently filled with anecdotes of such frustrations with online education. Students recount having to rush out of toilets to answer professors’ calls or turn off their video feeds to block out relatives yelling or playing mah-jong in the background. One group of students at the Chinese University of Hong Kong all changed their usernames to “NO SOUND” after a hapless professor continued to lecture with his microphone turned off.

Then again, such teething problems are only to be expected given the breakneck speed at which universities in China have been forced to move all of their teaching online – precisely to preserve the health of their students – in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak that has paralysed the region. The world’s largest higher education system has been thrust into an e-learning experiment of unprecedented scale and scope, as university medical staff scramble to address an epidemic that, by early March, had infected in excess of 100,000 patients and killed about 4,000.

All students in mainland China and Hong Kong – from kindergarteners to doctoral candidates – were asked to stay home and pursue their education online after the Lunar New Year break ended in late January. At the tertiary level, this affects 30 million learners at 3,000 institutions, many of which have responded by rushing to develop and launch mandatory online classes to fill a void that may endure for the rest of the academic year in the most severely affected areas.

Nor is it only Chinese students that are affected. Many of the half-million international students enrolled at universities in mainland China and Hong Kong have had to log in from their home countries to continue their courses. Meanwhile, Australia is also seeking online solutions for the estimated 100,000 Chinese international students who went home for the Lunar New Year and were then prevented by Australia’s China travel ban from returning to campus. The issue is particularly fraught in Australia given that the 2020-21 academic year has already begun but, if the epidemic endures, the same issue could affect other nations with large Chinese cohorts, such as the UK and Canada.

Universities in other Covid-19 hotspots, such as Italy, Iran and Singapore, have also closed their campuses, and Singapore has replaced in-person teaching with online alternatives for the time being.

But how realistic is it to suddenly shift large amounts of teaching online? Are the university leaders surveyed by THE right to assume that students will see the virtual student experience as a poor substitute for the real thing? Or might it be that online higher education becomes the new normal far earlier and to a far greater extent than any experts were previously predicting?

Asian universities were initially slow to embrace online learning. While The New York Times dubbed 2012 “the year of the Mooc”, the first Asian massive open online course, developed by the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, emerged only the following year.

But enthusiasm for Moocs has since waned and East Asia is strongly placed to pioneer a global move to deliver more mainstream university teaching online. Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore all have internet penetration rates of 85 to 95 per cent, and while that figure drops to a little over 50 per cent in mainland China, that still amounts to 840 million internet users: the largest national cohort in the world.

Moreover, “China is one of the most technically enabled countries in the world”, according to Hamish Coates, director of the Higher Education Division of the Institute of Education at Tsinghua University. In particular, he cites the Haidian district of Beijing, which houses a dozen university campuses, including Tsinghua’s, as well as the headquarters of Google China, Microsoft China and domestic technology firms Baidu and Xiaomi. “It is one of the biggest edtech hubs in the world,” Coates says.

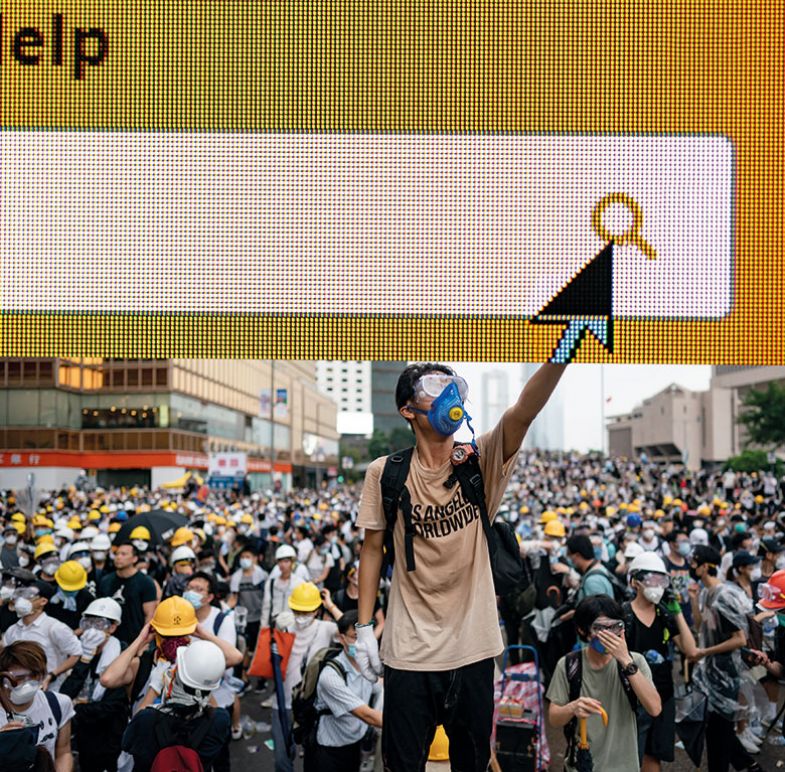

Hong Kong had a head start on transitioning to online education when its public universities replaced in-person classes and assessments with digital alternatives last November, owing to campus closures caused by the anti-government protests and police violence. Hence, apart from a few weeks in January, Hong Kong’s campuses have already been running digitally for a few months.

“The hardware, software and systems are all there,” says Yeung Yau-Yuen, an expert in IT and science education at the Education University of Hong Kong (EdUHK) and a visiting professor at Sichuan Normal University. “We don’t have enough bandwidth yet, but that will likely be solved with 5G.”

But Yeung recognises that the somewhat patchy and impersonal experience of Moocs is not a good model for universities to follow: “With the exception of some very top courses, the overall quality of Moocs may not be great,” he says. “And there’s a high dropout rate. Moocs are not the solution, as online teaching requires guidance. It needs to be interactive, with as much face-to-face learning as possible.”

EdUHK chose to deliver lectures and seminars via the web conferencing site Zoom. This required some training of lecturers, but the digital switchover was achieved with minimal delays.

“It’s not such a big deal. Hong Kong universities did it in two weeks,” Yeung says. “And the mainland has also been very fast. University students are already all online, and almost everything can be done on a mobile phone.”

EdUHK has established schedules and standards for the online lectures, and marks attendance for group classes. Regular absences, except under exceptional circumstances, can lead to failing a course. And despite the fact that the students are all sitting alone in a room, “there’s a sense of spirit, of enthusiasm, when you’re all together, even if on a screen”, Yeung says. “When you’re just learning online by yourself, it’s hard. You need learning companions. It’s good to see other students asking questions.”

He concedes that students can still find it hard to focus when they are surrounded by the distractions of refrigerators, games consoles and other home comforts. Hence, “you don’t get as great a response as you do being face to face. But it’s better than individual self-learning,” he says.

The digital shift has suddenly thrust universities’ IT departments to the forefront of managerial attention. Ian Holliday, vice-president and pro vice-chancellor (teaching and learning) at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), is now playing a direct role in the institution’s Technology-Enriched Learning Initiative (TELI). Staffed by two dozen designers, developers and IT specialists, the programme long predates the recent upheavals and was focused on facilitating flipped classrooms, Moocs and other digital innovations. However, the previous assumption that online learning was only a realistic option for tech-savvy teachers has been swept away, requiring TELI to “reach out to everyone at the same time”, Holliday says.

“Online learning has become central to our teaching model,” Holliday says. But he adds that he expects this to be the case only temporarily. Hence, some of the more difficult aspects of switching to online tuition wholesale have not been addressed. The teaching timetable has been rejigged such that “material that can be [easily] taught online comes first”, Holliday says. The university has also had to “rethink student assignments, especially as the logistics of group work are very challenging for students who are often living in very different time zones”. Assessments may also change, giving more weight to weekly assignments and less weight to mass final exams, which some HKU schools may struggle to hold online. But practical applications of knowledge learned, such as laboratory-based classes in medicine and science, have been postponed until the end of modules, by which time it was initially hoped that the campus would have reopened –although HKU announced last week that classes will now be cancelled for the entirety of the current semester, which runs until the end of May.

It is not only IT departments that have been stretched by the online switch. Lecturers, too, have had to make major changes to their work habits, and many report heavier workloads as they scramble to post their teaching materials online and get to grips with what online lecturing involves. Yeung, for instance, spoke to THE via a headset from his book-lined office during his seventh Zoom meeting of the day. He reports sometimes recording 10 videos for use in just one class, and now needs to do student assessments one by one, instead of as a group activity.

Meanwhile, Areum Jeong, an assistant professor at the Sichuan University – Pittsburgh Institute (SCUPI) in China, worked remotely from her native South Korea to prepare materials for online English composition and Korean film classes that began in late February, delivered via the BigBlueButton conferencing site. She compliments the university’s administrative staff for working “tirelessly, around the clock” to provide training sessions on how to use the site, and she is also grateful for the practical tips shared by fellow faculty and staff on the popular Chinese messaging platform WeChat.

Jeong has been practising lecturing with and without video, sharing clips and slides. She has revised her syllabi, set up course homepages and uploaded required readings. To try to keep her students interested, she has prepared in-class activities, group discussions, online polls and even updated her PowerPoint presentations to make them “more eye-catching”.

She admits that English writing can be a “boring and difficult subject” for students even at the best of times, especially for non-native-speaking science majors who may feel “uncertain and stressed” by lengthy essay assignments. “Establishing rapport with the students can be a very important factor in keeping them encouraged and engaged,” she says, adding that she normally tries to meet in person with students as much as possible during her office hours. In the absence of that opportunity, "adaptability and flexibility will be key”.

Still, there are some learning experiences that cannot be replicated digitally. Originally, Jeong wanted to hold regular movie viewings, plus Q&A sessions with Korean film-makers. Now, one of her students is helping her look for Chinese streaming platforms where the films can be viewed online, but she is sorry that the students will miss out on the shared experience of watching them together.

“I imagined classes filled with students eagerly sharing their opinions about specific scenes and asking questions about the film’s relationship with Korean history and society,” she says.

Hard evidence for the superiority of the classroom to the online experience is actually scarce. Indeed, educational researchers Robert Bernard, Eugene Borokhovski and Richard Schmid, from the Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance at Concordia University, Canada, told THE in 2018 that they knew of “no empirical evidence that says that classroom instruction benefits students (compared to alternatives) from a learning achievement perspective”. More important than the medium was whether university teachers could “capture and challenge the imagination, based on the learners’ pre-existing knowledge”.

The enforced pace of the online switch in China has not always made that easy to achieve, however – as the social media comments mentioned above illustrate. Anyone who has ever tried to set up a Zoom meeting knows that there are inevitable technical and scheduling problems when trying to link up 30 people, much less 30 million. Indeed, in the first few days, several major Chinese web conferencing platforms, including those of the huge domestic technology firm Tencent, experienced crashes after receiving tenfold jumps in traffic, such that the hashtag #TencentClassroomCrashed trended on Weibo, a popular social media channel.

China’s Ministry of Education announced in February that the nation had 22 online platforms providing 24,000 free higher-education courses, covering 12 disciplines for undergraduates and 18 at a “higher vocational education level”. These options will be helpful for regional or smaller institutions that may not have the means to produce online alternatives quickly.

Meanwhile, some elite institutions have gone beyond merely shifting their teaching online. Peking University, for instance, is also offering online trauma counselling, employment advice, thesis supervision and other support services. And some senior sector figures are convinced that while physical campuses will retain enormous value once the epidemic is over, there may be no going back to a fully analogue model of university instruction.

HKU’s Holliday, for instance, expects that “many colleagues will make permanent changes to their teaching practice as a result of what happens in these few weeks. Already we’re finding that while there are bound to be problems and challenges, some students and teachers are writing in to applaud the things they really like about online teaching. Our task will be to retain those aspects and integrate them with face-to-face teaching once the campus returns to normal.”

Tsinghua’s Coates also thinks that “there will almost certainly be a post-virus boom” in online higher education.

“We didn’t even know this was possible,” he says of mass online learning. “But now you have major university systems proving it to presidents, funders and governments.”

He adds that the main development that has taken place in the past few weeks is not so much a technical one as a cultural one among administrators and governments. “Online education has matured into the mainstream,” he says. “The big thing is legitimisation.”

Nevertheless, there remain likely limits to how far the longer-term digital switchover might go. That is because, however successful a university is in conducting its teaching online, there would appear to be no good virtual substitutes for field trips or academic exchanges – never mind the social and cultural attractions of campus life, from band nights to sporting events.

Christy Kan, a master’s student in journalism at HKU, has taken Moocs before, so has had no technical difficulties adjusting to online learning. However, she feels that interactions online can be “quite weird”, as some students prefer to turn off their computers’ cameras and microphones, leaving teachers to lecture to “black screens” for hours on end. In her experience, students also tend to ask fewer questions online, and some have had trouble making class because of time zone differences.

Asked about the prospect of longer-term campus closures, she responds: “No one wants this to happen!” Echoing the view of the university leaders who responded to THE’s 2018 survey, Kan adds that “as a student, I value campus life very much. Of course, the university can switch face-to-face learning to online learning any time, but the real-life campus experience cannot go virtual.”

joyce.lau@timeshighereducation.com

Tsinghua University’s digital revolution

The sudden outbreak of Covid-19 came at a particularly challenging time. Students in China were due to commence the spring semester around 17 February, but, under nationwide measures to control the spread of the virus, those not already on campuses were instructed to delay their return.

On 3 February, I chaired a special university-wide briefing to outline new semester arrangements at Tsinghua University. Live streamed to 50,000 students, faculty, staff and alumni, the briefing included lectures by the university president and chairperson and evoked previous arduous periods that Tsinghua has endured. The university’s determination to continue come what may is perhaps best encapsulated by the insistence of Mei Yiqi, one of Tsinghua’s most influential presidents, on delivering basic education and research in the face of persistent civil war and foreign invasion in the 1930s and 1940s.

Hence, although all campus-based classes have been suspended, except for some laboratory and practical course components, teaching for all courses has continued via online platforms. Extraordinary efforts were made to prepare faculty and students for the digital switch, and a total of 4,254 Tsinghua courses, taught by 2,681 faculty members to more than 25,000 students, are now being successfully delivered this way.

Even courses in creative arts and physical education have been conducted online. Physical education instructors use online tools to monitor students’ exercise and to instruct them on health and fitness. In addition, to ensure the holistic well-being of all students and staff during this uncertain and anxious period, mental health courses have been made available, and additional resources have gone into counselling services.

Many students and teachers have been excited by the move to remote learning. Faculty have supported each other during the implementation period, sharing their discoveries and tips as they navigate the online teaching systems. And observing colleagues’ online courses has become a convenient and worthwhile way to promote faculty development.

Meanwhile, the new online teaching model has encouraged those students who are typically shy about speaking in public and prefer to contribute in written form, so participation and engagement level are also expected to improve.

Tsinghua has been able to lead the way in China’s online transition because we had already made decisive moves into online teaching, in an effort to facilitate the learning of post-millennial students.

In 2016, for instance, we launched the Rain Classroom teaching platform, which is the most advanced and effective online teaching platform in China and currently has more than 19 million users, the second highest in the world. Online classes consist of three 30-minute sessions: a duration deemed more suitable than longer lectures for the pace of online learning. Students are encouraged to submit questions during live interaction with their teacher, which the software can collect and classify. Time is allocated for instructors to answer the queries and further discussion is arranged in each section of the course. Rain Classroom also facilitates course assessments and the setting and evaluation of both standard homework and extracurricular learning tasks.

But digital education isn’t only for registered students. Tsinghua has also decided to release all 1,600 of its Moocs free of charge, and we will open more than 2,000 Rain classes to the public, too. We will also set up “clone classes” so that teachers and students from other schools can share Tsinghua’s courses simultaneously. Several universities and local educational institutions, including secondary schools, have contacted Tsinghua in the hope of obtaining support.

Like many universities with medical schools, Tsinghua faculty have been assigned to research and develop medical responses to the coronavirus, and medical personnel from our affiliated hospitals have been dispatched to Hubei province, the centre of the epidemic, to assist in the treatment of patients.

In all these ways, Tsinghua is living up to its commitment to the academic community, and to society more broadly.

Once the immediate period of virus prevention is over, conventional classes will return in some capacity. However, the impact of the online switch will endure. Students and teachers will have collectively experienced a new benchmark of contemporary education: a more interactive, real-time and innovation-oriented learning experience. I am confident that teachers will embrace the digital switch, and even seek further opportunities to develop online and blended education models.

Some will still be resistant to change. In particular, some teachers still have concerns about using Rain Classroom and are reluctant to change their existing methodologies. But I know a professor in her sixties who had never used the online tool before the training sessions. She was understandably very resistant at first, but, after realising that her unique teaching style will not be compromised, she now supports Rain Classroom’s adoption.

In this unforeseen and unpredictable landscape, technology has offered credible solutions to an unprecedented problem. The online tools and upgrades to existing technologies that have been pushed to the forefront of university teaching will emerge as epoch-making platforms in China. They may well establish new global standards, too, and new norms for online and blended education.

Bin Yang is vice-president and provost of Tsinghua University.

Will India’s demographics reap a dividend for online education providers?

India has the third largest higher education system in the world, but it is marked by significant disparities in access to high-quality institutions. Official figures put the current enrolment rate only at about 25 per cent, and the student body is largely dominated by people from urban areas and higher income groups.

However, internet access is more widely distributed; cheap data costs mean that more than 40 per cent of the population are already online. With rural aspirations for a white-collar future increasing, conditions are ripe for solutions that can democratise knowledge and skills, and pundits are optimistic that online education can deliver that.

India’s edtech market is projected to be worth $2 billion (£1.5 billion) by 2021, based on 9.6 million users, according to a 2016 report by KPMG and Google. In 2016, it was worth $250 million, with 1.6 million users. A 2018 report on Indian edtech start-ups by industry body NASSCOM and consultancy Zinnov found that 3,000 edtech start-ups had been incorporated in the previous five years, backed by venture capital funds and other high-profile investors, such as the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Google and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

So far, the industry is dominated by apps that supplement school-level education or offer professional reskilling. The latter reflects India’s demographic dividend, with working-age people making up 62.5 per cent of the total population; industry experts predict 10 million enrolments in online/distance courses by 2021, with high demand from semi-urban and suburban areas.

Other rapidly growing market segments are preparation for undergraduate and other competitive exams, such as the GMAT (used in MBA admissions), civil service entrance exams and professional engineering exams.

There is obvious further scope. A 2019 report by Indian employability evaluation company Aspiring Minds claims that 80 per cent of Indian engineering graduates lack the skills for the knowledge economy. However, while edtech platforms such as Udacity and India’s own Unacademy offer courses on future-facing subjects such as AI and data science, prohibitive pricing limits access. A self-paced certificate on AI can set a student back over £600: a lot of money for a young graduate from the suburbs. An online MBA from Amity University costs more than £6,000.

Moreover, online education and edtech in India is still not integrated into the mainstream education system for the most part. There has been significant push towards online education by the government, which runs a slew of online courses on everything from languages to cybersecurity through its premier higher education institutions. And, in 2018, the University Grants Commission, India’s higher education regulatory body, finally approved new rules that allow all colleges and universities to offer fully fledged online courses, subject to meeting certain quality criteria. Proposals for new online degrees have also been solicited from other universities that fulfil those criteria, so more can be expected to start offering such programmes. However, such offerings are yet to take off on a larger scale.

Hence, while the emergence of edtech is undoubtedly a significant development in a higher education system which, by and large, still swears by traditional pedagogies, the jury is still out on how much it can actually deliver in terms of increased equity.

Rudrani Dasgupta works for ActionAid in Kolkata, India.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The virtues of virtual

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login