Striking a daily balance between work and life is “impossible” for researchers, a Nobel laureate has argued, and academics should instead “hope that things average out in the longer term”.

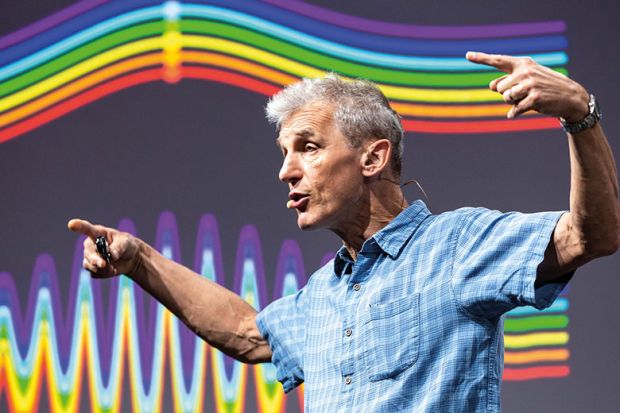

Wolfgang Ketterle, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who won the physics accolade in 2001, told early career scientists at a conference in Germany that there were times in his life when he had “neglected” his family to do physics.

“But then there were times I neglected physics to take care of my family when my family needed me,” he said.

His advice comes amid growing focus on academics’ sometimes punishing schedules and poor mental health. A Times Higher Education survey last year found that around a quarter of scholars were working 10-hour weekdays, and the majority were putting in hours at the weekend.

“Things can balance out in the longer term, but to balance something at a given time is almost impossible, because you may suddenly be close to a discovery and you are so excited and passionate about it you will neglect other things in your life,” Professor Ketterle told the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, an annual get-together where Nobel laureates offer advice to young researchers.

“The message I try to give is don’t get too worried if things are not balanced in your life at this moment. You have time – it’s more the time average that matters than the momentary situation,” he said.

Professor Ketterle, a keen runner, stressed that although science would be “dominant” at some points in life, it should never be “the only thing” researchers do.

While scientists should “work hard,” a seven day a week schedule would only lead to burnout, he warned.

Other Nobel laureates who also spoke on a panel discussion about career planning revealed just how important a supportive partner had been to their success.

William Phillips, a physicist at the United States’ National Institute of Standards and Technology, credited “luck”: his wife had a career that meant “she could go anywhere in the country and get a job, and that made things a lot easier for us”.

“She could decide that we should go here or there with the confidence that she was going to be able to find a job...and you know that’s not the way it is with a physicist, you really don’t have a whole lot of options,” Professor Phillips, who won the prize in 1997, told delegates.

He also revealed that when looking after his two young daughters, he would sometimes leave his lab at around 6pm in the evening, go home to have dinner with his family, read to his children and put them to bed – and then go back to the lab.

Donna Strickland, a professor at the University of Waterloo who won the prize last year, said that she got her first invitation to speak at an international conference while pregnant – but decided to attend nonetheless with her 14-week-old newborn and husband.

“I was having to run out to feed my baby in between the talks and my husband had to keep coming and bringing him back and forth. But it was worthwhile doing,” she told the conference.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: ‘Aim for balance in longer term’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login