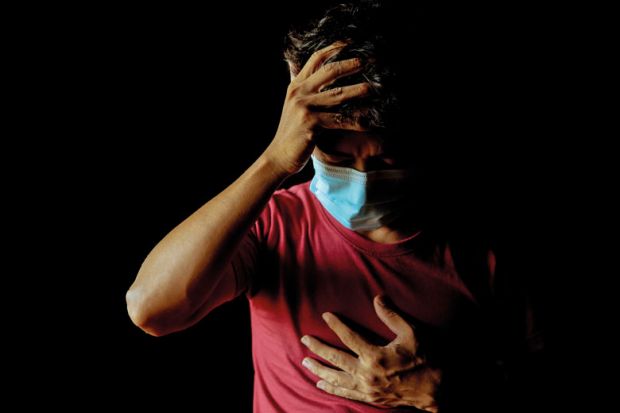

In a sector as overworked and competitive as higher education, the prevalence of long Covid among staff is something of a taboo subject.

Given that the condition is known to cause chronic fatigue and brain fog, academics have, perhaps understandably, been reluctant to speak out if they are still struggling months, and sometimes years, after infection, fearful that doing so might harm their career prospects.

But those with the condition say this has left thousands to suffer in silence and caused a quiet crisis in the sector, leaving classes untaught, work unmarked and key research projects lying dormant.

“We don’t know yet how to adapt to what seems to be a mass disabling event,” said Yannik Thiem, an associate professor of religion at Columbia University who has had long Covid since the start of the pandemic in March 2020.

“In academia, so much of our activity is scheduled, and that becomes very difficult when a significant number of people have conditions that fluctuate day-to-day and don’t abide by any kind of routine.”

Little data exist on long Covid in academia, but in the UK, the Office for National Statistics estimates that about 3 per cent of the population has experienced the condition, making it likely that almost all universities will have had some staff and students affected.

For institutions, this poses a series of difficult challenges: how to cover the workload of those affected without placing too much stress on colleagues, what to do about sick pay and how to support people back into work after a prolonged absence.

Dr Thiem said that while everyone on the academic side has been supportive, he has encountered problems with the HR department trying to apply “typically rigid” processes to what is a fluid, constantly changing situation.

“What makes it very difficult is long Covid symptoms are so varied and unpredictable; it is not like, ‘Here’s the one thing you can do to solve it,’” he said.

Dr Thiem has returned to work but is no longer able to clock up the 60-hour weeks he was doing pre-illness and must take regular breaks to ensure that his symptoms do not spiral. In a culture where overwork is a systemic problem, this “looks like you are not doing your job”, he said.

Several academics with long Covid who spoke to Times Higher Education said they felt pressure to get back to campus for fear of letting down students, but studies have shown that not resting and trying to power through only exacerbate symptoms.

One postdoctoral researcher based in Norway, who asked to remain anonymous, said his long Covid had cost him about six months’ research time, which, he fears, puts him at a disadvantage compared with his peers.

“From the very beginning, I should have taken a lot more time off. I do feel like I am often pushing myself too far,” he said.

“But I feel the pressure of the job market…when you have a bunch of people applying – and often these jobs are oversubscribed – employers are almost certainly taking the people who have been more productive.”

Kerstin Sailer, a professor in the sociology of architecture at UCL, has been unable to return to work since she was signed off on long-term sick leave in early December 2021. She describes feeling like a mobile phone battery that never fully charges.

Although her university has been “absolutely brilliant” from the start, she was recently informed that she would be receiving only half her pay because of her extended absence.

And while this does not affect her family’s finances too badly, she fears for others in a similar situation who might have to “choose between their livelihood and their health”.

In her absence, Professor Sailer’s essential tasks have been covered by a variety of people and UCL has drafted in additional resources to help – but everything else, including research, publications, public engagement and research grant applications, has been put on hold.

Despite the issues it raises, long Covid does not appear to be on the radar for many universities – but the academics who spoke to THE said a wider conversation was needed across the sector.

More immediately, sufferers said, universities could take steps to support those with the condition, including prioritising rest and time off and relieving pressure on affected individuals by offering contract extensions, opportunities to reduce workload and not using outputs such as papers published in performance reviews.

Covid mitigation measures such as mask and vaccine mandates are also seen as key because being reinfected has been shown to exacerbate symptoms, but many universities have instead opted to cancel all restrictions.

Professor Sailer said more awareness of the condition and its impacts would not only help staff to spot when colleagues or students might be struggling but would also spur institutions to develop long-term strategies to deal with the issues presented.

“Society does not feel ready to talk about this – understandably, everyone wants this to be over – but academia should be brave enough to address this, loud and clear,” she added.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: ‘This seems to be a mass disabling event’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login