Most nations have key years in their history when a major change in the law or an event altered the university landscape for ever.

In the US, few would argue against 1862 – when the Morrill Land-Grant Act led to the founding of many of the country’s best-known universities – as being one such date.

By bequeathing federal land to states in order for them to finance the establishment of colleges that would educate the “industrial classes”, primarily for the benefit of agriculture, the act started a process of creating universities whose mission was to serve rural communities across America.

But jump forward more than 150 years to a much more urbanised US, where such universities increasingly compete for recognition on a world stage, are they in danger of losing this powerful local link that was central to their creation? And how does this relate to the bitter political divide that appears to have opened up between urban and rural America?

An analysis of data from the Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education US College Rankings suggests that some land-grant universities might need to reassess their strategies and consider whether they are remaining faithful to these original missions.

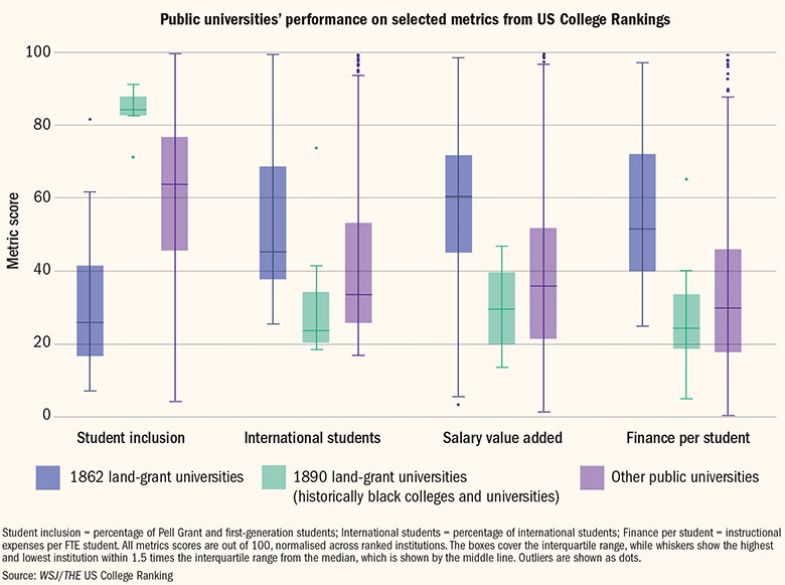

The analysis, carried out by THE data scientist Emma Deraze, examines the scores in some of the metrics achieved by the 1862 land-grant campuses in the ranking compared with other public universities and land-grant institutions set up under separate legislation in 1890 (which led to some of the historically black colleges and universities that exist in the US).

It suggests that while the land-grants set up under the 1862 act tend to outperform other public institutions on graduate outcomes and resources, their social inclusion scores – based on the number of first-generation undergraduates and students from lower-income families they admit – are lagging behind. Meanwhile, the eight historically black institutions covered by the analysis have very different profiles for inclusion, suggesting that they admit far more students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Stephen Gavazzi, co-author of Land-Grant Universities for the Future, a book published last year that looks at the current role of land-grant institutions amid the urban-rural political split in the US, said that such data might paint an uncomfortable – if not necessarily surprising – picture for university presidents.

The professor of human development and family science at Ohio State University argues that the increasing selectivity of student admissions at 1862 land-grant universities – which he believes is linked to the institutions’ desire to perform well in domestic rankings that measure the average scores on standardised entry tests of incoming students – has correlated with a lack of diversity.

“There are…many rural kids who by the very nature of the school system in America are not as well prepared to take [standardised university entry tests],” he said, with the result that many urban land-grant campuses, such as Ohio State, end up “having a largely white suburban incoming class [of students]”.

Although this might help such universities in national rankings, he said, it “completely blows them out of the water in terms of any efforts towards diversity, racial, geographic or what have you”.

“I don’t think this is going to come as a surprise to presidents and chancellors, but I think it’s going to feel like dirty laundry,” he said.

Professor Gavazzi said that some land-grant universities, Ohio State among them, did have regional campuses where the intakes could be very different because they operate “open admissions” policies. Referring to an Ohio State regional campus where he used to be director, he said that one in every two students there was eligible for a Pell Grant, federal financial aid for students from the lowest-income families. Students who did well at such a regional campus could later transfer to the central campus, he said.

“These are the working classes – or what the Morrill act originally talked about as the industrial classes – because that was what land-grants were supposed to be serving, the working-class individuals,” he said.

“The problem is that many of these land-grant universities do not have regional campuses, so [students from rural areas without the grades for entry] have to rely on the system of other public education.”

Professor Gavazzi worries that if these geographic class divides are not addressed, the increasing antipathy and even anger directed towards universities from rural communities – which has already arguably led to some state governments cutting funding for land-grant institutions – will only grow.

“There will be a continued disconnect between these universities and the people that they were supposed to be serving, and that is going to pay some enormous penalties down the road,” he said.

Peter McPherson, president of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the urbanisation of the US population in the past 150 years had “naturally shifted some of [the universities’] focus [on to] these communities” but it would be “unfair…to say that this evolution means land-grant universities have lost touch” with rural areas.

Land-grant universities still have what are known as “extension” offices “throughout their states – even in the most rural areas”, which were originally a product of a system brought in by an act of Congress in 1914, he said.

“The services offered by these offices are tailored to community needs, and the extension agents are important leaders in their communities. They provide a connection point to the campuses,” Mr McPherson said.

“Some universities are implementing projects to use this network to reach out to offer opportunities for rural students to prepare for college work and to understand their options for attending and paying for college.”

However, Mr McPherson acknowledged that students from rural communities had particular challenges related to a lack of resources in their local schools, their distance from major cities and the high proportion of low-income families. He also added that land-grant universities “have become, by necessity, more selective” because of the huge increase in the number of applications.

Another controversial finding of the data analysis is that 1862 land-grant universities have clearly embraced, more than other public universities, the recruitment of international students, shown by their performance on a ranking metric that measures the share of overseas students on campus.

This on its own was no bad thing, said Professor Gavazzi, but if universities were not careful it could end “looking like an aggravating factor. I think if we were doing a better job of inclusivity at home, this would mean something different; it would mean we are being inclusive at home and abroad.”

There is also the irony that such institutions have been forced in some ways to recruit more international – and out-of-state – students, who pay higher tuition fees than local students, in part because of cuts in funding at the state level, something noted by Mr McPherson.

“There is no question that international students and out-of-state students who can pay full…tuition…end up [covering] the in-state student cost. And of course the states have made cutbacks in their appropriation [funding],” he said.

For Professor Gavazzi, it all goes to emphasise the vital importance of finding ways to show rural communities how their land-grant universities can benefit them, as that would then make it easier to make the political case for state funding. But, for him, that requires a shift in culture in land-grants back towards community engagement.

“Excellence in teaching and excellence in engagement with the community are not rewarded at the same level,” he said.

“If people valued [inclusion] more…then what a different world we would be in. So I think our value systems have to change. I would rather Ohio State be known for its inclusion than for its research dollars, personally.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Former fixtures of rural life risk losing touch with roots

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login