Increasing politicisation of student mobility poses a challenge to universities’ internationalisation efforts but online learning may present new opportunities, a conference heard.

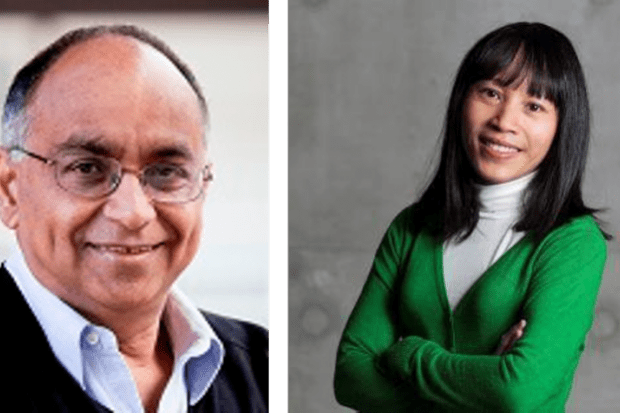

“Sadly, international education has been weaponised,” said Ly Tran, professor of education at Deakin University, during a virtual conference hosted by the University of Hong Kong (HKU). “Learning abroad is no longer just about serving individual students’ educational needs and institutional partnerships, but about nation-states’ political, diplomatic and economic agendas.”

Professor Tran cited destabilising factors in the West such as “Brexit, the rise of far-right parties in Europe and Trump’s isolationist policies”. She called the US attempt to cancel thousands of visas for Chinese students and scholars a “widely criticised and highly problematic approach”.

“Sadly, Chinese students have become the victims,” she said. Meanwhile, Covid-related racism affected students of Asian descent all over the world.

However, Professor Tran said there were also regional tensions within Asia. China has had territorial disputes with neighbours; mainland China and Taiwan have engaged in the “reciprocal banning” of students; and Beijing has hinted that it may lessen student flows to critical nations like Australia.

“China is trying to influence geopolitics through international education,” she said, adding that decisions could be swayed via partnerships, research funding, offshore campuses, as well as initiatives such as Belt and Road or Confucius Institutes.

To address the issue, Professor Tran advised that connections had to be built at all levels: “people to people, institution to institution, country to country”.

“Institutions need to consider the value of multilateral relationship-building and regional unity,” she said.

Fazal Rizvi, professor in global studies in education at the University of Melbourne, told the conference that “new mobilities of culture have also given rise to new problems”.

Students’ physical locations were no longer the only factor in helping them have a global mindset, as geographic distinctions “collapse” when most communication goes online. “The student in Melbourne who spends two hours a day on WeChat and Weibo is in Australia and China and the same time,” he said.

Betty Leask, emeritus professor in the internationalisation of higher education at La Trobe University in Australia, pointed out that only 2 per cent of students worldwide could engage in overseas study programmes. “It’s an elite experience for a minority of students,” she said.

However, digitising cross-cultural experiences would allow a far larger number of students to participate. “This may be a watershed moment for internationalising [the] curriculum, and developing international perspectives at home,” Professor Leask said.

Ian Holliday, vice-president (teaching & learning) at HKU, agreed that in more affluent parts of the world, physical exchanges often meant “substituting one elite campus for another. And that experience is great, but it’s a ‘bubble’ experience. It’s the international student bubble.”

On the other hand, “online internationalisation can promote global citizenship, more so than through physical mobility”, which requires costly flights and accommodation, he said.

An expert in Myanmar studies, Professor Holliday noted that only a small fraction of citizens there had internet access a decade ago. Nowadays, many young people have smartphones and connect globally through Facebook and Instagram.

“Given these tools, Hong Kong students themselves can be teachers, especially to students in parts of the world without the same resources,” he said.

Professor Holliday had been working towards this goal even before Covid. When he was HKU’s social science dean, he introduced a requirement for students to complete off-campus credits in global citizenship, and also set up a programme for students to teach English to less privileged communities in south-east Asia.

Now, the push to online learning caused by Covid offered more opportunities to reach across borders. “It would be shameful if we didn’t move in this direction,” he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login