Finding ways to fairly evaluate the standard of university teaching has been a hotly debated topic in recent years, one that in the UK has reached fever pitch thanks to the dawn of the teaching excellence framework.

And that is even before attempting to find a way to compare teaching standards from one country with another.

However, the publication of Times Higher Education’s Europe Teaching Rankings – and the European Student Survey underpinning it – offers some new resources to try to unpick how different higher education systems fare when it comes to pedagogical performance.

Although the data are far from perfect – the first year of the survey and ranking is very much a pilot and features only about 250 institutions across eight countries – there are already interesting insights that are emerging about the strengths and weaknesses of teaching in different nations.

Some of the more fascinating insights can be found in the student “engagement” pillar of the ranking, which makes up 40 per cent of each university’s final score. It is comprised of five separate metrics that reflect results from the survey, which canvassed the views of about 30,000 students across the continent on how their university performs on its teaching.

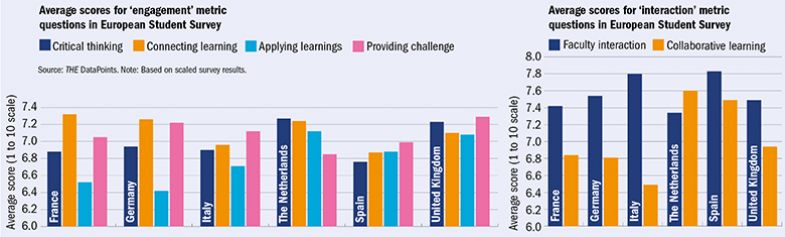

On the metric that specifically looks at how engaged students are with learning, the UK and the Netherlands appear to gain the best responses while countries such as Spain and Italy noticeably lag behind.

But the other metrics in the pillar sometimes show different results: on student interaction – based on whether learners feel able to collaborate with each other and connect with academics – Spain clearly comes out on top while the UK is, at best, average.

The six survey questions that underpin both these metrics reveal even more about the possible strengths and weaknesses of different teaching cultures.

For instance, Spanish universities on average do particularly poorly for how well students feel their institution supports critical thinking (apart from a couple of outlying universities that perform very well).

These are results that do ring true with those who know the Spanish system well.

José Manuel Martínez, director of the Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard University and a former Spanish government adviser, has spoken before about how the country’s system is slanted towards individuals learning hard facts rather than developing the skills to challenge and question what is in front of them.

“It’s a system that has privileged increasing the gigabytes of information that the student received and, as a consequence, it has resulted in a narrowing of the space that faculty and educational leadership at centres and universities had to promote critical thinking,” he said.

Professor Martínez said that some university teachers had managed to “stray off the predetermined path” and pass on these skills to students but that they were often fighting against the tide.

“The space available in the educational system is only reserved for those professors that – due to their vocation, a sense of personal responsibility and with the ability to do so – manage to carve out that space and make the most of it in order to impart such important skills,” he said.

Professor Martínez said that the Bologna Process, aimed at harmonising higher education systems across Europe, had been a bit of a “missed opportunity” to move Spanish teaching in the right direction on this front.

However, he also noted that Bologna could be the reason that Spain does well on interaction because it had encouraged and enabled universities to use “different formats, such as seminars, workshops or tutorships”.

“That has ultimately allowed higher education institutions to pay more attention to instruction focused on practice rather than plain and simple lecturing,” he said.

Looking across the results of the two survey questions underpinning the interaction metric shows that Italy also competes well with Spain on how students view their interactions with teachers – but not so well on collaborative learning.

Of the other countries with more than 10 universities in the ranking, the Netherlands has a strong showing on both survey questions, but it is notable how others, such as Italy, are much weaker on collaborative learning than on interaction with academics.

Ready for your close-up? Continental comparisons

Please click here to enlarge the graphic

Meanwhile, looking under the bonnet of the engagement metric – underpinned by four survey questions – also shows some interesting trends across the same group of countries.

France and Germany have a very strong showing on how they support students to make connections between what they have learned, but appear weaker on applying learning to the real world, for instance.

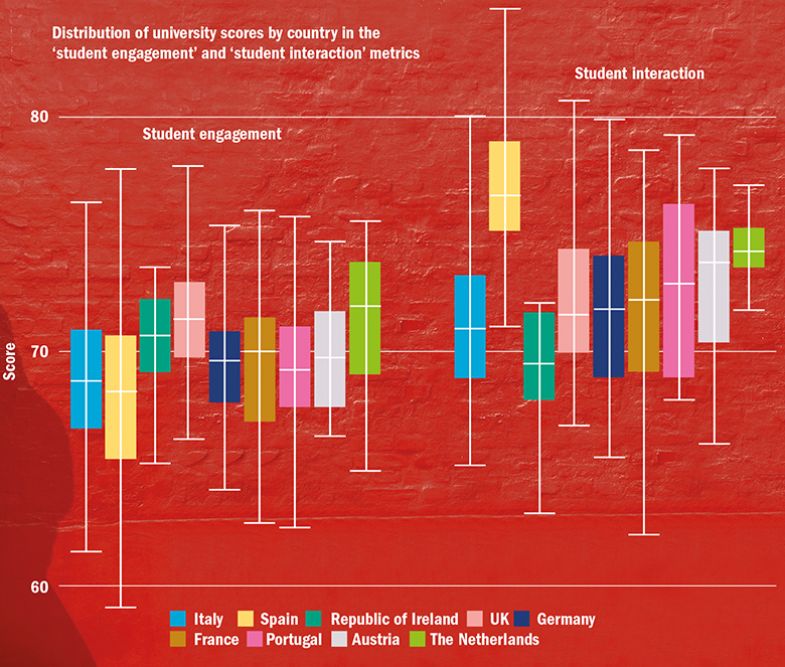

Hans de Wit, director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College and former president of the European Association for International Education, cautioned that strengths and weaknesses in teaching differed just as much between universities in a country as between nations.

There were also myriad factors influencing the state of teaching in higher education across Europe, including history, culture and access from secondary education.

But Professor de Wit said that it was possible to observe that institutions in central and eastern Europe were still “emerging” when it came to teaching standards, while those in southern Europe were possibly “slow on improvement”.

“But even there it is difficult to generalise, as several universities – for instance the [polytechnic] universities in Italy and private universities like the Central European University in Hungary…are doing great work,” he said.

Professor de Wit also pointed towards the important distinction between the differing missions of “research universities on the one hand and universities of applied sciences and some specialised institutions in their approach to teaching”.

This is where much richer data from the survey covering more types of institution will be invaluable in the future for providing a clearer picture of teaching across Europe.

For instance, the results for Germany – which performs poorly on how well students feel they are being prepared for a career – have to be seen in the context of the survey and ranking featuring a large number of research institutions and many fewer applied science universities.

“Around 400 universities of applied sciences have their main strength in practical and labour-market orientation,” pointed out Frank Ziegele, executive director of Germany’s Centre for Higher Education.

“Germany’s strength is underestimated by only looking at the ‘usual suspects’, the comprehensive research universities.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Who is the strongest of them all?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login