As public funding has tightened across the West in recent years, efficiency has become a mantra for policymakers trying to make the most of the limited money available.

This has been as true in higher education as anywhere, as universities and funding bodies are implored to make the best use of resources.

In research, this has led to a variety of approaches to make the money go further, including the sharing of expensive equipment between institutions and the close management of grant funding.

The UK – where research funding was frozen in cash terms for several years as part of the coalition government’s austerity drive – is a prime example of somewhere these measures have been used.

It means that despite constant calls for the share of gross domestic product being invested in research to be uplifted to compete with other nations, the UK is still held up as an example of a system that produces top research despite constrained budgets.

But how does the UK compare with other countries facing a similar squeeze on public funding? And does a drive for efficiency bring potential problems that are sometimes unseen?

One way to explore the first question is to use data in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings on citation impact and research productivity and compare these with university income.

These metrics were used at the latest THE Awards to look at UK universities that were producing the most “bang for the buck” in research, with the University of Leicester coming out on top.

The same method can be used to assess bang for buck in other institutions around the world, as well as national systems. At first glance, this seems to support the idea that the UK has a leaner research system: its universities feature 13 times in the top 20 institutions for this “efficiency” score.

Country averages taken across the whole ranking of about 1,000 institutions do suggest that universities in the Netherlands, Sweden and Australia are more efficient.

However, to a certain extent this may be skewed by the UK’s having a large number of universities spread right across the ranking while the Netherlands has all its 13 institutions in the top 200 and Sweden’s 11 are all in the top 500.

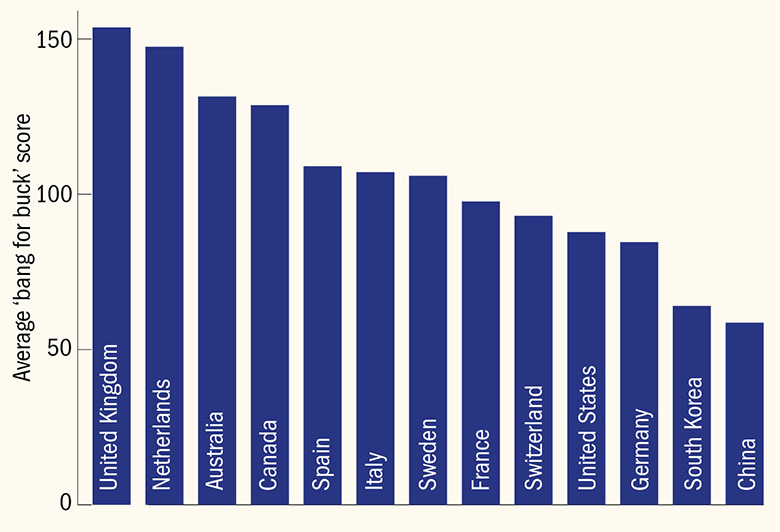

Attempting to limit this effect by taking the average from only the 10 highest ranked institutions in each country shows that the UK does come top in the world for bang for buck, followed by the Netherlands and Australia.

Average ‘bang for buck’ scores for countries based on top 10 universities in THE World University Rankings 2018

Note: Scores come from comparing citation impact and research productivity with income

Source: THE DataPoints

So on this evidence, the UK can rightly claim to have an efficient system for producing world-class research, at least when looking at the data for the highest-ranked universities.

James Wilsdon, professor of research policy at the University of Sheffield, said that such an analysis did accord with other studies that had suggested that the UK and countries such as the Netherlands were among those with especially efficient research systems.

However, he cautioned against concluding that countries such as the US or Germany were inefficient because they sometimes had fundamental structural differences.

“I wonder if that is a product of the fact that a lot of the research is not going on within the universities [in those nations],” Professor Wilsdon said, referring to the “more structurally diverse” US system, including government-funded labs, and the existence of specialist institutes in Germany.

“In the UK, so much more of the research takes place in the universities than anywhere else,” he added.

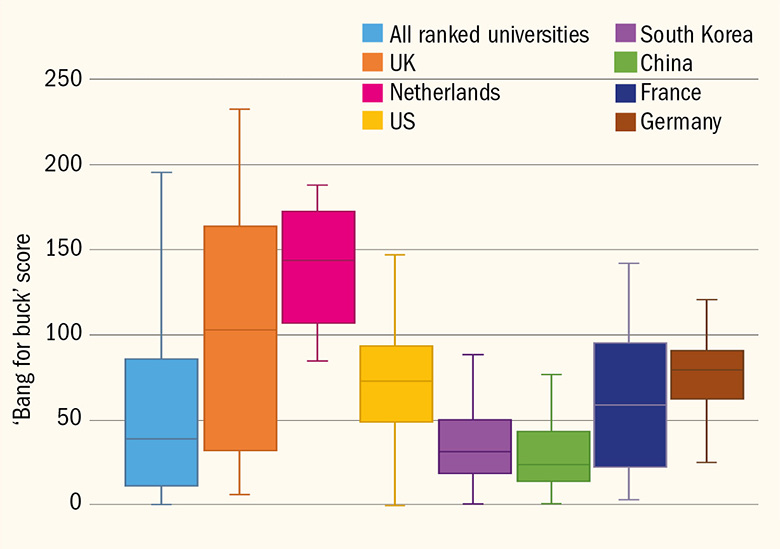

This might help to explain the vastly different distribution of universities on the efficiency score for these countries, although they still fare better than emerging research nations such as China and South Korea, which have been pumping money into their systems for longer-term gain.

Distribution of university ‘bang for buck’ scores

Boxes show interquartile range of distribution

Source: THE DataPoints

However, Professor Wilsdon said it was interesting that most of the countries with the highest bang-for-buck scores “are all systems that have some form of national research assessment exercise”.

Although there was a lot of debate about the influence of the UK’s research excellence framework on scholarship, he said, it was likely that it had encouraged academics to publish work that “might not have seen the light of day” otherwise.

That the REF determines part of the public research funding that each UK university receives might arguably be another driver of efficiency.

Leicester did not do as well as was hoped in the 2014 REF, according to its vice-chancellor, Paul Boyle, but it has since produced a new strategic plan that includes a focus on improving cross-disciplinary and collaborative working. Among the developments has been the setting-up of four research institutes in fields where Leicester excels, such as precision medicine and space sciences.

This approach has led to an increase in the amount of highly cited work being produced, which is now bringing in more grant income, Professor Boyle said. He said he was confident that it would also lead to better results in the next REF (although ironically both this and higher grant income could lower Leicester’s bang-for-buck score by increasing resources).

Professor Boyle, former head of the Economic and Social Research Council, added that "research councils will always think about bang for the buck because they are in charge of public money and thinking about the best way it can be spent".

However, he added that it was important not to concentrate resources solely on academics and projects that had already demonstrated excellence.

“It is a balanced approach – yes, excellence is the priority, but measuring that can be challenging and it is important to identify and support those growing areas that will underpin some of the most exciting advances in the future,” he said.

This question of balance in striving for efficiency is one also taken up by Jesper Falkheimer, head of the research division at Sweden’s Lund University, an institution that Professor Boyle said he had drawn inspiration from in its approach to collaborative research.

Lund is among the highest-placed Swedish institutions in the efficiency analysis, and at a national level Professor Falkheimer pointed to both “solid financial conditions for research” and programmes that “guarantee healthy competition” as contributing to this.

“There seems to be a systemic balance between certainty and uncertainty which [drives] research productivity,” he said, adding that Lund itself benefited from a “high level of decentralisation in decision-making” and administrative support for researchers.

But what are the dangers for research of losing this balance and pushing too far on efficiency?

Professor Wilsdon said that although efficiency was often a helpful “by-product” of research assessment, there were dangers in making it “a primary end in itself”.

“If efficiency is the real goal, then you tighten and tighten the funding system…and that has a lot of negative consequences, which are in fact inefficient,” he said.

He gave the example of success rates for grant applications that, if too low, stop good researchers applying and waste academics’ time and energy working on proposals that never get funded.

“You might be storing up long-term structural problems in the system that come from systemic underfunding of…more exploratory work that could yield the big successes 10 years down the line,” Professor Wilsdon warned.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Are lean, mean research machines setting themselves up for a crash?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login