Ever since the file-sharing website Napster quickly devoured the music industry’s traditional business model in the 1990s, observers have been wondering when higher education’s “Napster moment” would come.

It seemed obvious that teaching could be done effectively online. Indeed, some higher education institutions have been doing just that for many years, but most contented themselves with blended learning, secure in the assumption that even school-leavers born into the digital era would still value the full campus experience.

But then Covid-19 came along, forcing universities across the world to pivot within days from a physical to a digital teaching environment. Such transformation has been hailed as something of a miracle. But how successful has it really been? Do students value the online education experience they are receiving? Are they learning effectively? And what about academics? Is lecturing from home a blessing or a curse? And how long beyond Covid should it endure?

These are the questions that Times Higher Education has sought to address in our Digital Teaching Survey. Carried out in October and November, the survey attracted 520 self-selecting respondents. And although the majority (334) are from the UK, a total of 46 countries are represented in the responses, spread across all continents bar Antarctica.

Among the findings are:

- More than half of respondents say the initial move to online teaching had a negative effect on their mental health, and nearly six in 10 believe it hit their students’ mental health.

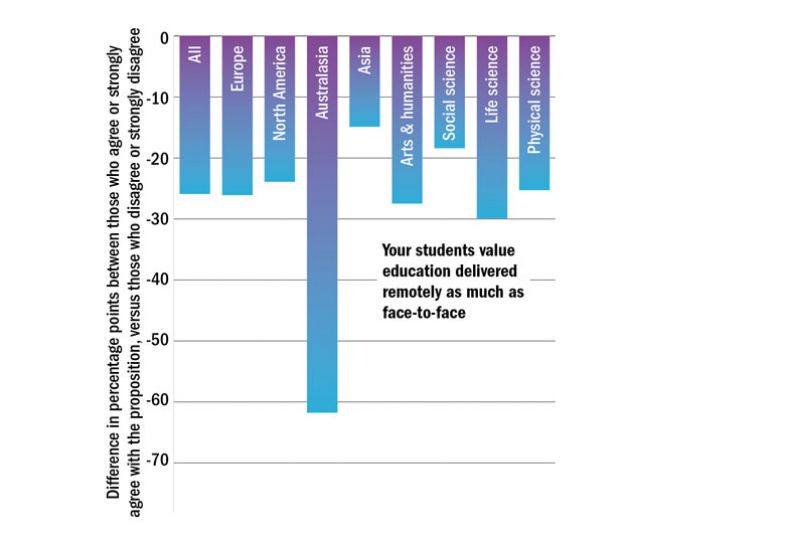

- Only a fifth believe that their students value remote education as much as face-to-face, but less than a third think tuition fees should be discounted when instruction moves online.

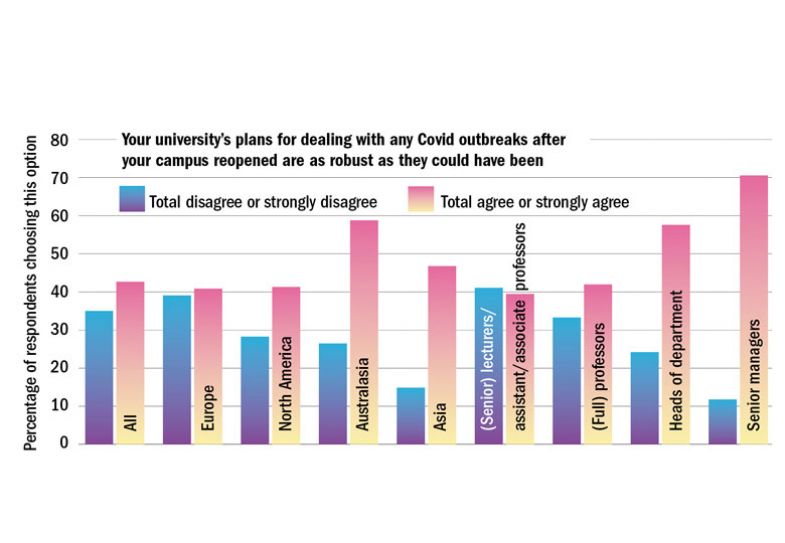

- Only four in 10 junior academics believe their reopened universities’ planning for Covid outbreaks is robust, compared with seven in 10 senior managers.

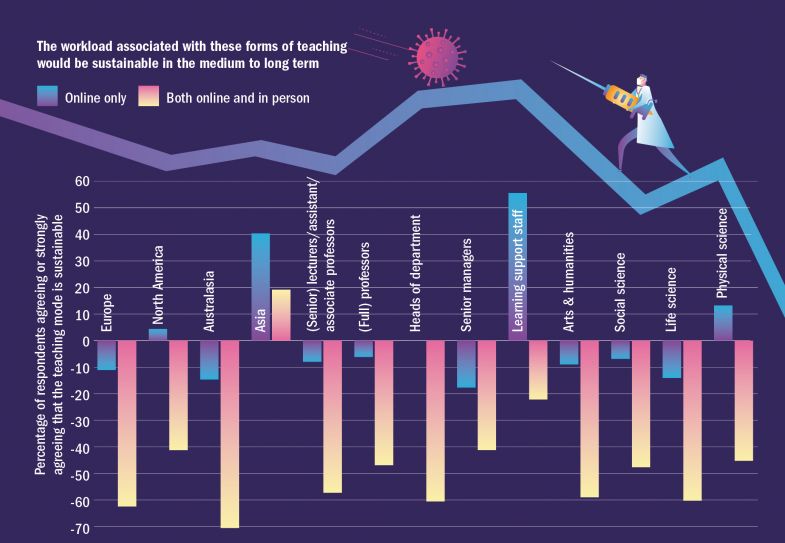

- Less than a fifth of respondents regard the two-track physical and online approach to teaching as sustainable, while two-fifths regard an online-only future as sustainable.

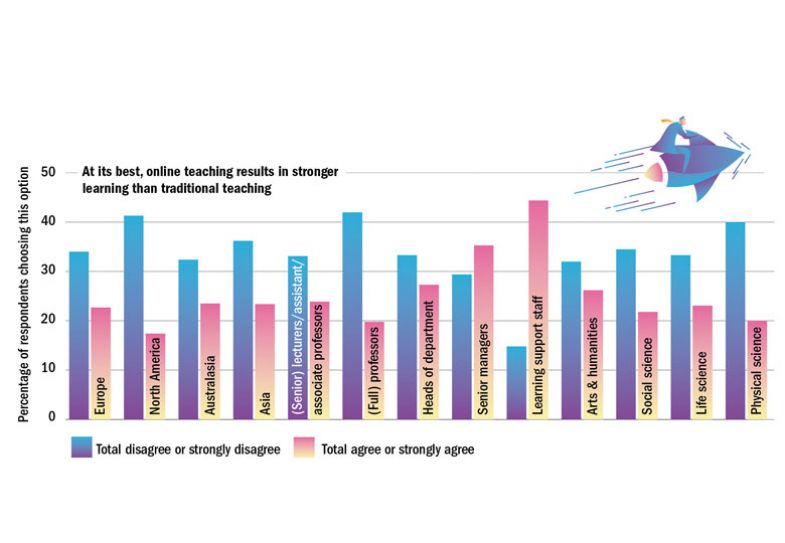

- Respondents are mostly unsure whether good online teaching results in stronger learning than traditional teaching, but more than twice as many disagree as agree.

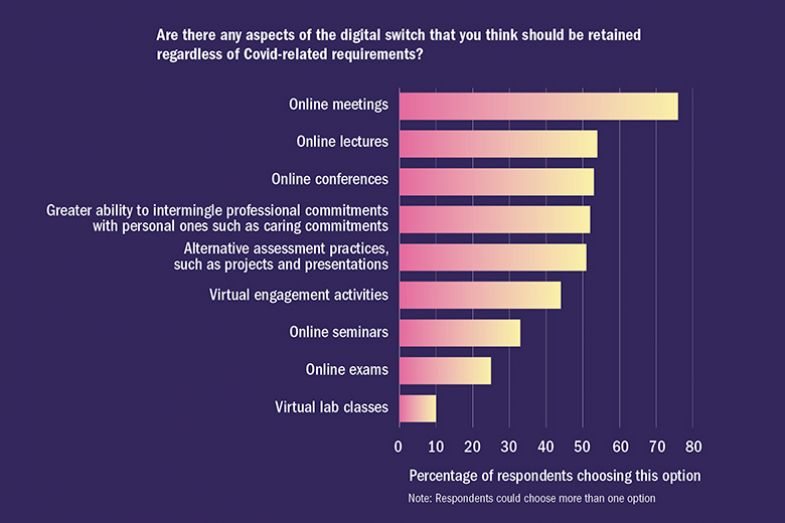

- More than three-quarters would like online meetings to endure beyond the pandemic.

The first wave

Universities’ previous reluctance to embrace online teaching is reflected in the fact that only 26 per cent of respondents had a “reasonable amount” or “a lot” of experience of online teaching prior to the pandemic, while 36 per cent had none at all. And while some respondents had previously taught on distance learning courses, these were often asynchronous. As one humanities lecturer puts it (all quoted respondents are UK-based, unless otherwise stated), such experience “was largely irrelevant in the current context, where my institution was expecting us to replicate the experience of face-to-face teaching online”. Indeed, while a professor in the physical sciences had previously made a lot of use of their university’s virtual learning environment (VLE), they “hadn’t even heard of Zoom or Teams until [the] start of lockdown”.

So how much of a helping hand did universities offer their academics when they were plunged in at the deep end? Overall, 47 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that they were well supported by their institutions to make a successful initial transition, but 33 per cent disagree or strongly disagree.

“Our learning and teaching development team have been heroic. They were supporting us from the beginning and introducing us to best practice and theory in digital pedagogy that we could apply at once,” says a senior lecturer in humanities.

A head of department in the humanities adds that their institution “has an effective VLE and a good track record of supporting/training staff to use it. Lecture capture and electronic reading lists have been the norm for some years, again with central support. It was a strong base on which to build.”

A senior lecturer in humanities supposes that their university “did what they could in an unprecedented situation. But it was a continuous process of improvisation and the goalposts seem to change daily with new task after new task being thoughtlessly thrust in our faces through seemingly ceaseless internal communications. No one seems to have given a moment’s consideration to what the cumulative effect of all this might be, especially in terms of stamina, morale and mental health.”

Casual staff felt particularly abandoned. One objects that they were “not paid to undertake training in various new digital tools, whereas permanent staff attended training in their normal working hours”. Nor, adds another, were those who did the training in their own time guaranteed any work in the next semester.

A social science lecturer complains that all of their university’s training was “focused solely on pedagogic ideas – for example, ‘you can embed emojis’ – with no step-by-step guidance of what to press, how to set up Teams/groups/online learning spaces. It was incredibly stressful, frustrating and demoralising.”

A social science lecturer “had to battle for six months to get institutional support with internet access”, since broadband is unavailable in their area. They also had to wait five weeks for a new laptop, during which they had to work on their phone; this “affected my eyesight, as well as my neck and back”.

Meanwhile, a lecturer in environmental sciences was disturbed by their institution’s apparent lack of concern about “ensuring high standards could be met”. When they asked for guidance, “the individuals involved were very helpful, but…they seemed surprised that anyone wanted to edit, blend, improve material. The general feeling is that our institution wanted to take as little responsibility as possible in sorting this out and instead relied on the usual route of keeping their heads down and hoping most of the investment in time and money would come from the teaching staff themselves. As a strategy, it worked.”

A common refrain is that the most useful source of help was colleagues who had already grappled with the problem in question.

Whether students were able to make the most of the digital resources made available to them is unclear. Asked whether their university offered students training to help them adjust their learning methods to digital environments, respondents were split roughly equally between “yes”, “no” and “I don’t know” – although those in North America and Australasia were more certain that their students had received no training.

“An assumption was made that all students are very tech-savvy,” says a business and management lecturer in Australia. “This is not the case and some need more support than others. I believe students were largely left to their own means to figure things out as they went along.”

A senior lecturer in life science says everything at their university was left to course directors. “General guidance from the university to all students irrespective of subject would have been helpful: a short online, interactive guide could have been produced, for example. The shortcomings of internal systems such as timetabling, due to underinvestment, hit everyone, but teaching staff were left picking up the pieces and trying to help students navigate through systems that the staff themselves have no access to.”

A professional in learning support confesses: “[The training] has been minimal from the educational development team and poorly received by students. The learning development team is trying to pick this up as a matter of urgency, but with very little support or resourcing.” Things would have been so much better, they add, “if we had been given more freedom to innovate and if those who had expertise had been allowed to lead. It’s really discouraging to know we could have done better.”

Initial workload

Whatever the quality, it is remarkable that universities were able to offer at least some form of online education at such short notice and in such unprecedented social circumstances. But THE was interested to explore the human cost of such superhuman effort. And the answers make for grim reading.

Asked whether, domestic commitments aside, their workload increased following the transition to online teaching, 61 per cent of respondents strongly agree and another 28 per cent agree. Just 4 per cent disagree or strongly disagree. The sentiment is consistent across all disciplines, regions and levels of seniority, but is strongest among academics in Australasia (where 97 per cent agree or strongly agree).

“Everything online takes considerably longer,” says a South Africa-based senior lecturer in life sciences. “Online marking is a nightmare. Marking a basic test went from eight hours to five days. I had to work late each day and every weekend for several months to just keep up with my teaching.”

A senior lecturer in the same discipline notes that the real killer is “multiple repeats of socially distanced practical sessions – but creating online resources takes around three times longer than continuing conventional lecture/tutorial/practical approaches”.

A Canada-based humanities professor estimates that emails from students quadrupled, mostly relating to technical questions, while their office hours had to double to deal with students’ anxieties and loneliness.

A humanities lecturer says that “to deliver the equivalent of a one-hour lecture takes at least 3-4 hours for recording and uploading (usually in several shorter segments). With editing and captioning, it’s more like 8-10 hours. Seminars also require a lot more preparation. We have to spend a lot more time communicating with students and explaining to them how things work…When student services, registration, welfare and IT services get overwhelmed by the demand, the students come to their teachers or personal tutors instead.”

A common refrain is that managers fail to acknowledge the full extent of this workload. “They seem to relate to the issue only through use of the institution’s workload planner, which has been adjusted to make the load look tolerable,” the humanities lecturer says. “I am working over 70 hours a week and not quite keeping up with teaching and day-to-day admin, yet my ‘official’ workload is at about 95 per cent [of my capacity]…People are falling apart, while our managers seem convinced that everything is running smoothly.”

But senior managers evidently worked very long hours, too. One in social science worked “14-hour days during the week and several hours every weekend day for months on end. As an SMT [senior management team] member this was unavoidable, but there is a human cost here for all of us. It’s been successful but horrendous at times.”

Of course, perceptions of how bearable a workload is during lockdowns has a strong relation to respondents’ domestic situations. Those without conducive home-working spaces or with caring responsibilities struggled to bear even their standard workload, never mind an increased one. So was this borne in mind when workload was allocated? On balance, the answer is yes. Asked whether their managers showed consideration for their domestic and personal situation during lockdown, 42 per cent agree or strongly agree, against 36 per cent who disagree. Positive sentiment is strongest among respondents in Asia (55 per cent).

“We were given a three-day ‘well-being break’ once the June exam boards were over in gratitude for all the hard work...Also, research demands were reduced,” reports one senior lecturer in the social sciences. Another in the life sciences appreciated their institution’s “best endeavour” policy, whereby “if we were trying to fulfil our roles, they were happy”.

But it is clear that not everyone felt the love. An hourly-paid teacher in the humanities and social sciences reports that “no manager even asked about my domestic situation”. Other staff received support they regarded as merely performative. A professor in the social sciences received “lots of encouraging words and links to mindfulness apps, but workload pressure has been piled on”.

Another common refrain is that while immediate line managers were considerate, universities’ directives from on high were anything but. A life sciences lecturer was grateful when their head of department relieved them of responsibility for organising one module because they were “doing too much”. However, “the university senior management has been abysmal – plenty of nice words about how they appreciate how difficult it is, but then taking decisions that increased workloads, such as not allowing us to hire extra tutors to help with marking.”

A senior lecturer in social sciences objected to his institutional management’s apparent belief that those who seek accommodations are trying to abuse the system. “After the first two months, HR did concede that those with caring responsibilities could not be expected to perform at the same level and in the usual working hours, but it was made clear that they were still expected to work the same number of hours at some point in the day. And there has been no financial support. I have spent at least £1,700 to be able to work at home, which has placed me in financial hardship.”

It was a similar story for a business lecturer in Australia, whose neighbour was having their house renovated with the help of “a jackhammer only two metres from my study…When I asked for leave because it was impossible to work, I was told to ‘work flexible hours’, which meant completing tasks between 7pm and 2am. It was disappointing and callous.”

Mental health impacts

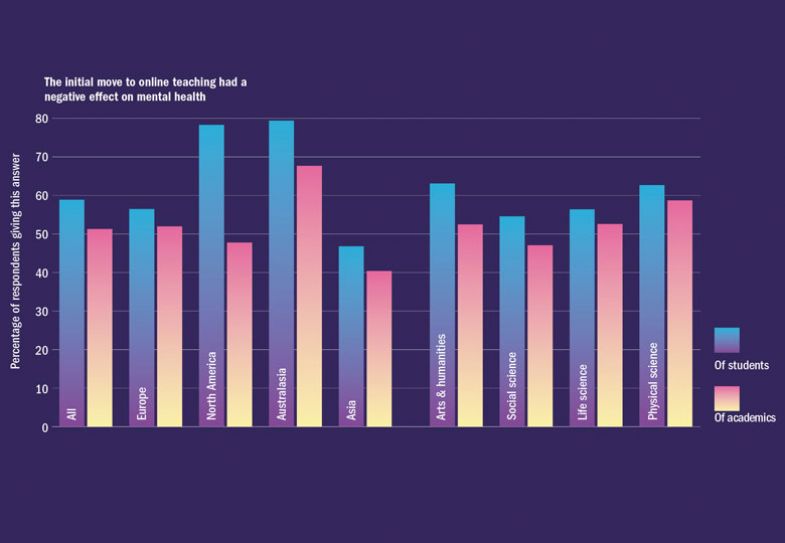

All of this appears to have taken its toll on well-being. Asked whether the initial move to online teaching had a negative effect on their mental health, 51 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree, against 27 per cent who disagree or strongly disagree. Affirmative answers rise to 68 per cent in Australasia and fall to 40 per cent in Asia.

The head of a careers education department greatly enjoyed “not to have a daily commute of 80 miles or get up at 7am. Absolutely fantastic. Stressless mornings.” And a senior lecturer in the humanities “hadn’t realised how much stress getting to rooms on time, keeping eye contact with different locations in the room and remembering keys/markers/etc was causing me until I didn’t have to do it (I am dyspraxic and may be neurodiverse in other ways). I feel able to be so much more relaxed with students in online teaching than I am when I am meeting them in a classroom.”

A US-based assistant professor in the humanities was “grateful to reduce the Covid risk, but stressed about redesigning classes from home with an infant”. A social sciences professor felt “extreme anxiety about the technology, about my students, about having the time to update and augment my learning materials. All of which the university was happy to encourage.” And a visiting lecturer in the social sciences “felt trapped at the computer because the email torrent was ridiculous and that was the only way to keep up with all the changes”.

Such pressure triggered some specific mental health episodes. A social sciences lecturer suffered, for the first time in their life, with anxiety and an eating disorder, resulting in several weeks of sick leave: “The mass uncertainty, lack of institutional (and financial) support, and increased demands was crippling.”

A senior lecturer in the humanities “eventually had something approaching a breakdown. Even suicidal thoughts. It sounds crazy to me looking back at it now: not like me at all. But it was as real as day at the time. I ended up spending two months off work with severe depression.”

A management lecturer in Australia also had to take sick leave. “The [online] move itself was not so much the problem, it was the unrealistic management directives. They kept pretending things didn’t take the time or effort they did and then falsely reported what great feedback they were getting from students when many staff knew directly from the students themselves that they had found it chaotic at best.”

But, again, the idea that senior staff had it any easier is not borne out by the survey. The senior manager in the life sciences genuinely believes that they have post-traumatic stress disorder. “I’m stressed, anxious, ill – the same as 90 per cent of my colleagues,” they say. “But I’m management – nobody listens. Nobody cares.”

Students and learning

Concern also abounds about students’ well-being. Among our respondents, 59 per cent agree or strongly agree that learning was adversely affected by the digital switch (with the sentiment strongest in North America and Australasia) against 12 per cent who disagree. Across all geographies and disciplines, students’ mental health is considered to have suffered more during the initial lockdown than that of academics.

“The lack of training really impacted the staff and students,” says a Thailand-based lecturer in physical sciences. “Initially, the students had heard about how in the future all learning will be online and were excited about the switch. Within two weeks, they were desperate for in-person teaching to return.”

A senior business and management lecturer in Australia notes that their students were affected by “the stress of the global crisis. We have to remember we were offering remote learning in intense crisis conditions, not offering specially designed online courses. On a more mundane level, most students commented on missing in-class interactions, and that they found it harder to ask follow-up questions and participate online. At first, we had a small number of students really excel as they threw themselves into study [having been] furloughed from their part-time jobs. But as our very strict lockdown continued (100+ days in Melbourne) it took an obvious toll on many. There were also difficulties teaching students across time zones and in different places, with some students having remained enrolled but returning to their home countries. They tended to be disproportionately disadvantaged.”

Another big issue was computer and internet access. “Some students relied on the university for accessing computers...Supporting them in applying for funding took time,” notes a senior lecturer in a health-related field. “Some were using their mobile phones for internet access, but some apps didn’t work well on phones.”

A life sciences lecturer’s students “missed socialisation with their peers, and felt very uncertain about their futures. In some cases, they were in countries with quite strict lockdown rules and were stuck inside most of the time. I checked in regularly with my advisees and the main report was one of struggling with a lack of motivation.”

A senior humanities lecturer in Australia became “a sounding board” for their students to “lament and/or vent. This took an accumulative toll on me over the semester and a fatigue that spilled into the next: something that management was not interested in hearing about.”

By contrast, a senior lecturer in business and management reports that few of their students “fussed” and those who did “were weak students anyway and I think they are trying to take advantage of university leniency with Covid. I have no idea how being ‘stuck at home’ could negatively impact on your ability to get assignments done!”

But there is an easy answer to that question when it comes to the sciences. In our survey, 82 per cent of respondents who work in a lab-based discipline believe that the loss of physical lab time had a significant detrimental effect on their students’ education. “Science teaching without labs is a sham and we deserve scorn for accepting it,” says a senior lecturer in the life sciences. “The virtual platforms available have as much relevance to real lab work as any other computer game. None!”

But some universities managed to maintain some practical elements of courses. A physical sciences professor was able to schedule “a full quota of (socially distanced) lab time”. But “labs are usually a very social activity and we have lost all that. Students aren’t building up the same level of relationship with staff that they normally do and are going long periods without labs.”

The senior life sciences lecturer in South Africa also redesigned their lab exercises to ensure social distancing, but still had to “fight with line managers [who were] constantly trying to stop the classes” despite the lack of evidence that they had resulted in any Covid infections.

So how did attendance of online lectures compare with standard lectures? Just over 37 per cent of respondents report that it dropped – in 18 per cent of cases by a lot; interestingly, attendance in social sciences dropped off by considerably more – 43 per cent – than in other disciplines. But 29 per cent saw no change, while 22 per cent actually saw attendance increase.

“Students who would not have turned up to in-person teaching now log on,” says a teaching associate in business and management. However, “we suspect some do not listen in, as they do not respond when asked a question. Others have not done the prep and are ‘freeloading’ on those who have.”

The senior lecturer in a health-related discipline tells a similar story, reporting that, six weeks into the autumn term, more than 40 of their students had not accessed any online course material. And a computer science lecturer complains that many students arrive late and leave early to their online lectures; “few students have ever walked out of my face-to-face lectures halfway through,” they note.

The careers education head of department adds that “the introverts finally had peace and many came out of the proverbial woodwork and did every task set. Others had, as one of my students told me, a ‘lazy lockdown’.”

Evaluation and assessment

That mixed picture is reflected in students’ evaluations of lockdown teaching. Overall, about 40 per cent of respondents know that their institution carried out teaching evaluations during the initial period of online teaching, with prevalence particularly high in Australasia and Asia. Of those, 55 per cent of respondents report that their scores were largely unchanged from what they typically receive for the same course delivered in person. But slightly more (25 per cent) received worse scores than better scores (21 per cent). Interestingly, the biggest gap between better and worse scores was not in the sciences, where lab access has been an issue, but in the arts and humanities, where 35 per cent of respondents received worse scores than normal.

However, a New Zealand-based senior lecturer in environmental planning and management has not even had time to look at their evaluations. Nor are they in any hurry to find the time. “If bad, [the assessments] would have further affected mental health; if good, so what?”

Despite the difficulties of switching to online teaching during a pandemic, 56 per cent of assessed respondents were held to account for their ratings in the usual way, and only 23 per cent were not held to account at all. Indeed, some respondents feel that the scrutiny only intensified. “The university is continually sending students evaluations and it has a team of graduate students who can access our Moodle sites and assess quality despite not being academics and having no teaching qualifications,” reports a social sciences professor.

But a lecturer in education had a better experience: they were not so much held to account as “sympathetically encouraged to collaborate and solve problems together [with colleagues]”.

Beyond the Anglo-Saxon world, academics also seem to have had it easier. “There are evaluations but most students don’t do them. Teachers are not accountable,” says a Germany-based humanities lecturer, while a professor of education in China reports: “I am a distinguished professor. No one holds me accountable for anything. I hold myself accountable for work at a high standard.”

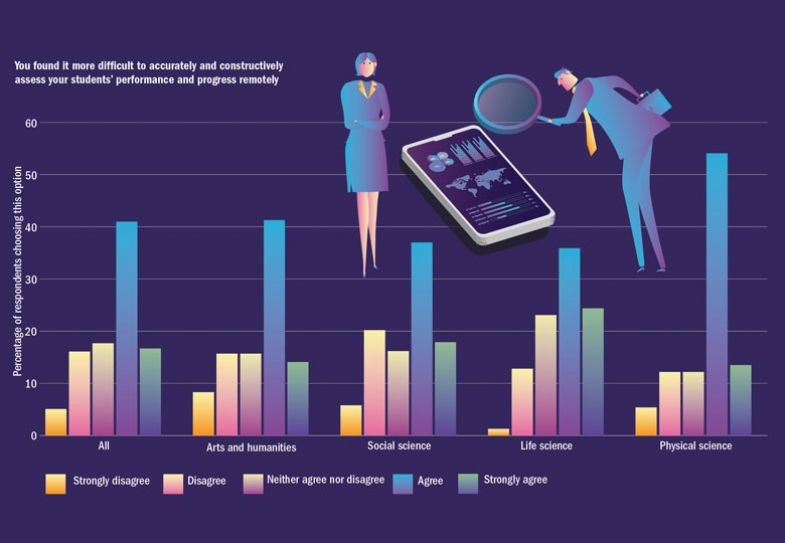

As for holding students to account for their academic progress, 59 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that they found it more difficult to accurately and constructively assess their students’ performance and progress remotely, against 21 per cent who disagree or strongly disagree.

“Because of the extra pressure on students and the loss of access to resources (in particular, the closure of the library), we had to quickly adapt or cancel assessments,” says a humanities lecturer. “Most of my modules adopted a part-for-whole approach, where assessments that had already been completed stood for the whole mark and uncompleted assessments had to be abandoned.”

Others worried about the integrity of assessments. “The first lesson that students have to learn is academic honesty and that is hard to monitor when teaching remotely,” says a professor in a health-related discipline. “I do not see how [cheating] can be overcome without severely penalising such behaviour (eg, by giving negative marks).”

The senior lecturer in a health-related discipline, for instance, tried an online version of their standard presentation exercise, in which the use of PowerPoint or scripts is banned: “Online, we asked the students to prerecord their presentation. You could tell most were reading and not using prompt cards, but we were unable to prove it.”

The Thailand-based lecturer in physical sciences didn’t even try to replicate standard exam conditions, opting for an open-book exam instead. Despite this – and the extra time given – “the scores were little changed from a normal exam. This is something I hope to revisit in this year’s class,” the lecturer says.

As for monitoring student progress less formally, a senior life sciences lecturer laments the difficulty of spotting “the facial cues of cognitive dissonance when the most you ever see is a tiny image on a computer screen”, while a US-based humanities professor has “no way of telling what is confusing students or if they are engaged. I ask questions but don’t know if I am getting honest answers.”

Others, though, had more positive experiences: “Students have been much more ready to contribute to weekly online discussion boards,” says a senior lecturer in business. “This has allowed me to see their level of understanding of the topic at an individual level. With 400 students on the module, this has been a terrific improvement.”

Another senior lecturer in business saw results from meeting students on Microsoft Teams to discuss their assignments: “It worked really well: better than emailed drafts and discussion.”

Fees

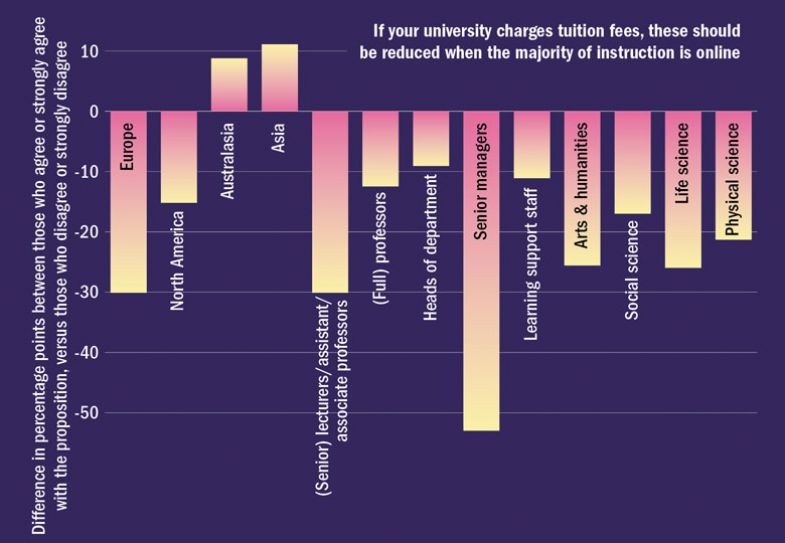

There have been regular calls from students in countries that charge tuition fees to have those fees reduced when teaching is moved online – particularly during that first term. Just over 30 per cent of our respondents agree or strongly agree that this should happen – rising to 41 per cent in Australasia and 45 per cent in Asia. “The quality of online teaching in my area just cannot match what studio-based practice offers in terms of teaching, space and group work,” says a director of teaching and learning in art and design.

However, overall, 52 per cent disagree with fee reductions. One reason is the sheer amount of effort that academics put into the online switch; as a humanities lecturer puts it: “I get that the quality of the experience is not as good, but everyone has invested so much time and money in ensuring students get the best deal they can.”

Others point out that online education is no cheaper than face-to-face to deliver, while the student experience is similar – except that “the students can sit in a more comfortable chair with a coffee at home”, as a senior lecturer in art and design puts it.

But the main reason for rejecting discounts is the realisation that in fee-reliant systems, reductions could impose huge financial strain on universities.

“If the students are enrolled in face-to-face courses and planned to be on campus they should be compensated for the lack of available facilities and the fact that they are not getting what they paid for,” says the senior business lecturer in Australia. “But universities here will not do that as they are significantly down on revenue with the loss of so many international students since the border closures.”

And declining revenues have knock-on effects on staff and students: “The university is already making redundancies,” notes a senior lecturer in life sciences. “If tuition fees are reduced, it will not have enough income to keep enough staff, and quality of teaching will decline substantially.”

Other respondents are irked by consumer-minded students’ lack of understanding. “They treat us like performing monkeys, just there to fill them with the exam answers,” says a law lecturer. “They do not see we are struggling too. This is not of our making and if they would just meet us partway it could be better for everyone.”

The second wave

When Covid cases in the northern hemisphere dropped over the summer, many universities chose or were required to re-start physical teaching – with the proviso that they might have to revert to online if significant outbreaks occurred.

Views are mixed on the merits of universities’ planning for dealing with outbreaks. Just under 43 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that their university’s plans were as robust as they could have been, but 35 per cent disagree, 16 per cent of them strongly. Academics in Australasia – where outbreaks have been relatively isolated – are most complimentary. Perhaps unsurprisingly, positive answers are also more frequent among senior staff. While 40 per cent of lecturers, senior lecturers or equivalent regard their university’s plans as robust, 71 per cent of senior managers do.

“My impression is that management started the term with the assumption that there would be no outbreaks, and was then caught by surprise when outbreaks happened,” says a humanities lecturer. A senior lecturer in life sciences agrees: “Repeating ‘campus is Covid-secure’ does not mean that it is,” they add.

A social sciences lecturer complains that when students disclosed positive Covid tests, “the institution did not contact any other students in the class nor staff. Worse, when we raised this with management, they wanted us to persist with in-person teaching.”

A lecturer in the environmental sciences describes the situation as “a shambles”, adding that “if it had not been for the dedicated efforts of a small number of academic and technical staff in departments, this institution would have been completely unprepared for dealing with the changing circumstances. The university management spent the summer constantly trying to provide information and guidance which made sure that they could not be held responsible for anything (presumably in case anything went wrong).”

Many respondents are critical of the decision to reopen campuses. “It is clear that the priority of the university is financial survival,” says a lecturer in art and design. “Without income from [accommodation] halls, this is unlikely.” However, the lecturer blames a UK government that has “thrown the sector to the wolves”. Italian universities, which do not rely on fees, found it easier to keep their campuses closed. A humanities professor in the country reports that their teaching remained entirely online through the autumn term, their president’s view being: “Why run the risk while the pandemic is not under control?”

Others have a more positive perspective on physical reopening. “Cross-faculty working groups were established and the institution works closely with the local council and health board,” reports the head of a humanities department. And a senior social sciences lecturer feels “safe going on to campus. Students appreciate the adaptations – one-way systems, smaller groups, distancing in classrooms, use of masks, hand gel and so on.”

Moreover, respondents are generally happy with the technology now available to them for online teaching. Just over 45 per cent agree or strongly agree that their university is now well set up in that regard. “Teaching staff have been provided with webcams and other necessary equipment in offices, and the software works reasonably well,” says a humanities lecturer. “There are ongoing software glitches, issues with some students not having good connections and so on, but, on the whole, things are working reasonably well.”

However, the 36 per cent who disapprove of their university’s technological preparedness are more vocal. “There is still a disconnect between the tech support available and tech staff’s understanding of instructor goals and needs,” reports a Canada-based assistant professor in humanities.

Several respondents report a particular problem with Chinese students’ access to platforms and websites. “We have to deliver a uniform online experience to students, so we can’t use the best technology. It’s made everything really difficult and unsatisfactory for us all,” one says.

Respondents also have ongoing problems with access to good hardware. A senior lecturer in the life sciences is “still having to use a four-year-old laptop that can only just about cope with Zoom, which was a replacement for the first laptop that I was provided with, which was constantly failing over the first four months. My internet access is a major problem and it is impossible to work with the files that are produced for online learning. This has meant that, despite being in a vulnerable group, I am having to come into the university to work effectively.”

A senior lecturer in the life sciences was “berated for not taking up the offer to use the recording equipment that had been set up specifically to help staff prepare online lectures. However, at the time we were not allowed onto campus!” Moreover, a clampdown on spending means that “even when we identify a resource that we think is important, such as a 360-degree camera, we are told there are no funds”. Several respondents report having resorted to buying the equipment they need out of their own pockets.

Technical support is also a bugbear. “There is bucketloads of self-help guidance,” reports a senior lecturer in the life sciences. “But if you get stuck and ask for help, it seems that few people really understand how the technology works. It is usually just luck to find the academic nerd who has spent hours working it out and who is willing to help you.”

As for professional development, 51 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that their universities have actively helped them to improve their online teaching skills in the months since the initial digital switchovers, while 35 per cent do not.

“This has been a priority,” insists an academic development professional in a social sciences department. “It’s happening at scale in a very short time period…although I’m hopeful that the time and effort put into new teaching approaches will be useful as new and innovative pedagogical approaches are embedded in the curriculum.”

But views are mixed about the quality of the training provided. “It wasn’t very good. It never is,” says the humanities professor in the US. And while a UK-based humanities lecturer reports that training events run over the summer by internal specialists in distance learning and learning technology were “mostly fine”, they also attended “‘training’ events which turned out to be little more than marketing presentations from edutech companies who were disturbingly blasé about students’ privacy”.

Moreover, many respondents still complain about a lack of time for attending training. A US-based professor in business and management puts it succinctly: “Seminars have been helpful. An online teaching course is available. No time to do it.”

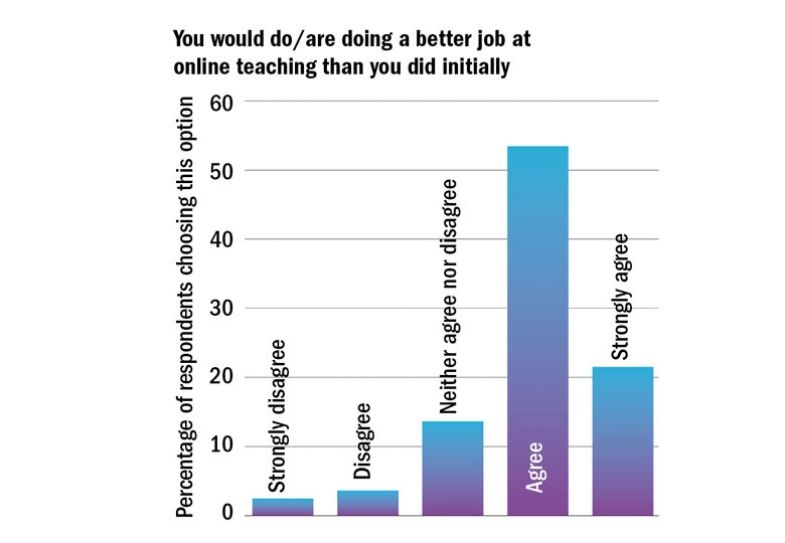

Nevertheless, an overwhelming 75 per cent agree that they are doing or would do a better job of online teaching the second time around, 22 per cent of them strongly agreeing, while only 6 per cent disagree or strongly disagree.

“Making errors helps one to learn and do better,” notes one senior social sciences lecturer, who has also “taken the initiative to attend lots of free-access, high-quality webinars about online teaching offered by universities from around the world”. And a teaching associate in business and management plans “to adapt and be more creative, moving away from the standard content I am asked to deliver, so that it is more engaging and more effective for the students”. But a humanities lecturer is merely “doing now roughly what I did [after the initial lockdown], but with more prep time”.

Ongoing workload

So has the initially high workload associated with digital delivery eased? One problem is the uncertainty of the Covid situation, obliging many academics to plan and deliver classes both online and in person. Of our respondents, 67 per cent were asked to prepare classes both online and in person ahead of the most recent term or semester, although in Asia the figure was significantly lower (47 per cent).

Indeed, some respondents prepared online alternatives even when university managers were hell-bent on in-person provision, in anticipation of virus outbreaks. A social sciences lecturer, for instance, “knew it would not be possible to deliver [my course] in situ (not enough staff or rooms to accommodate social distancing)”.

Respondents are deeply sceptical that the workload associated with this twin-track approach is sustainable in the medium to long term. Only 18 per cent agree that it is, while 69 per cent disagree – 42 per cent strongly.

“The structure and activities for face-to-face frequently do not work online, and vice versa,” says the senior business lecturer in Australia. “Before the pandemic, these would have had to have been taught as two separate courses, therefore attracting more adequate preparation time.”

Others report that sustainability comes at the expense of other academic duties. “No one is conducting research,” reports a lecturer in art and design.

The pressure is such that the Canada-based humanities professor has “considered retiring a decade early, and I know people who are retiring early or who have left the academy early in their career over the workload. And, of course, there’s no hiring, so their work is redistributed.”

The US humanities professor adds: “We are all exhausted! I have been on antibiotics twice this year already. We are not well.” Nor is that an isolated remark. “The majority of staff are in burnout and breakdown territory,” says a senior lecturer in the social sciences. “I feel like I’m cracking up with the pressure,” says a reader in the life sciences. “I might die of overwork,” says the head of a UK law department.

Senior managers, too, are feeling the strain. “It is like a war zone,” says the one in the life sciences. “I am seeing staff falling one by one, and less staff means even more work. Students need more pastoral care now, but how can we offer this working until midnight?”

Respondents are more optimistic that the workload associated with online-only delivery would be sustainable in the medium to long term, although there are still more doubters (44 per cent) than affirmers (40 per cent). Respondents in North America are marginally more inclined than disinclined to consider the workload manageable, while those in Asia are overwhelmingly so, by a margin of 40 percentage points. Those in the physical sciences also consider the workload manageable on balance, and while even senior managers do not, heads of department are evenly split.

While a senior lecturer in life sciences found it “exhausting” to adapt their lectures to online, once it is done “it becomes like any course, [although] you always want to make things better, add in new material and change things”. A business professor in the Philippines agrees: “After initial preparations, there are now curated materials and test banks.” And the senior lecturer in environmental planning in New Zealand has “learned how to teach without needing to edit the recordings afterwards, and much more of my core material is now available in pre-recorded PowerPoints or specialist topic lectures that will not require any extra work”.

But in the experience of a social science lecturer, “online teaching demands much more clarity of task and time for students”, while the senior life sciences lecturer in South Africa confesses that most of their face-to-face teaching “is out of my head. That is very difficult to do online when most of what we do had to be recorded.”

Others feel oppressed by institutional stipulations: “Management does not seem to appreciate that the creation of asynchronous materials that have to link to ‘live’ synchronous materials involves a huge amount of work,” says a teaching associate. “Huge investments have to be made in improving the technology and looking at examples of good practice. I feel I am reinventing wheels and creating poor-looking materials that I am not proud of.”

Meanwhile, many respondents make the point that face-to-face workloads are already unsustainable. “Digital is no better than face-to-face” in that regard, says the senior business lecturer in Australia.

The future of teaching

Workload aside, would it be a good idea to make the online experiment a permanent switch? On that question, the jury largely remains out. Asked whether, at its best, online teaching results in stronger learning than traditional teaching, 42 per cent of respondents are unsure. But more disagree (35 per cent, 12 per cent strongly) than agree (23 per cent). Disagreement is strongest among respondents from North America, those at professorial level and those in the physical sciences. But senior managers (by six percentage points) and learning support staff (by a huge 30 per cent) agree that the best online education is more effective than in-person teaching.

“It has to be better! You cannot get away with poor quality teaching interactions online,” says a senior life sciences lecturer involved in learning support.

But, for a senior life sciences lecturer, “with online teaching you cannot, no matter how hard you try, get the same level of interaction, discussion and debate, even with the most advanced platforms. There is difficulty in facilitating learning, as opposed to ‘teaching’, as you are unable to ‘read’ and respond to non-verbal feedback in real time. Most of the time, you feel as if you are talking to yourself.”

A senior lecture in the physical sciences notes the difficulty of socialisation online. “We know how important this is for learning. Plus, most technology tools for synchronous teaching are rather poor for good groupwork.” On the other hand, a senior social sciences lecturer found that “having synchronous sessions helped with groupwork online so students felt ‘together’ as a community of learners. International students need to make friends quickly, so groupwork tasks helped, as did breakout rooms for chatting in real time.”

Many respondents argue that online learning has both pros and cons. The head of a health-related department in New Zealand notes that the advantages of online learning “include accessing resources beyond the limits of a room’s geography and in providing accessibility to courses where time is no longer a limiting barrier”. A business lecturer in Singapore says: “It depends on the learning styles of the students as much as the capabilities of the teacher to deliver.” And a senior social sciences lecturer notes that “students who last year were anxious in the classroom, overshadowed by more confident students, are thriving” online, while those confident students “do not have the staying power for online learning: they tend to be quick thinkers, but often shallow learners”.

According to the senior humanities lecturer in Australia, online learning is superior, but “only when it is designed and developed over a two-year period before it goes live” because it requires significant investments of time and intellect, not least to address questions of “pedagogical integrity” and equity.

That latter issue is a common concern. A full 63 per cent of respondents believe that online teaching is at greater risk than traditional teaching of leaving behind students from non-traditional backgrounds, such as underprivileged, first-generation and mature students. Moreover, 26 per cent strongly agree with the proposition, while only 19 per cent disagree or strongly disagree.

“Some of my tutees’ work suffered [because] they didn’t have a quiet place to work without young relatives or a good enough network to be able to participate in live online teaching,” says a senior lecturer in the life sciences.

An hourly-paid lecturer in the social sciences adds that “students with disabilities are struggling with having to watch long online lectures, especially if they are live and not pre-recorded. This can be due to ADHD and concentration difficulties, or physical issues such as pain.”

However, the Canada-based assistant professor in humanities notes that provided students have digital access and a conducive environment, “social stigma may be lessened in online settings”. And others point out that any potential problems can be anticipated and mitigated by, for instance, extended one-to-one sessions with students.

When a social sciences postdoctoral fellow’s mostly non-traditional students were asked which teaching mode they preferred, “the overwhelming majority favoured online because it allowed them to care for their kids and extended families at home; work at their own pace around other demands like employment; fulfil their religious commitments; revisit prep materials several times before and after synchronous discussion sessions”. It also “obviated the need to spend long times and much money commuting to campus”.

Nevertheless, when asked whether their students value remote education as much as face-to-face teaching, only 21 per cent of THE’s respondents agree or strongly agree, while 47 per cent disagree or strongly disagree. In Australasia, the figures are a startling 3 per cent and 65 per cent respectively.

“Everyone I’ve talked to (over half my students in video meetings) dislikes the online medium,” says the humanities professor in Canada – although “I’ve heard no concerns about content”. Meanwhile, for the senior life sciences lecturer in South Africa, “the evidence of considerable cheating suggests that many of our students don’t value education at all”.

Others note that online education requires a level of self-discipline and maturity that school-leavers may lack. “It is clear that many working students prefer the flexibility of listening to recordings,” says a senior business lecturer. “However, many students are not taking responsibility for their own learning, as they need to in order to get the most out of resources available to them.”

Meanwhile, the senior physical sciences lecturer in Thailand notes that internet infrastructure in Thailand is “too poor to be a long-term, sustainable teaching solution”.

Ongoing work preferences

What about respondents’ personal preferences about how the future should look? They certainly would rather not be on campus until vaccines are administered. Asked if they enjoy teaching online more than in person under Covid-19 restrictions, 50 per cent agree, against 31 per cent who disagree, with a similar split in all regions and disciplines.

“I can run an online seminar using breakout rooms and small group discussion in ways that are close to what I would normally do in the classroom,” notes a humanities lecturer. “With 1m+ distancing, face coverings and students being required to face the front, peer discussion and group work are essentially impossible. Colleagues who have made the situation work well have been directing students to do their group work online and use the in-person class to report their results, but it means that almost all interaction is between student and teacher, not between student and student.”

A social sciences lecturer in Spain adds: “It is stupid to teach face-to-face, putting in danger students and yourself. Teaching under a mask is very difficult and, besides, I have a student with listening problems that would not be able to read my lips. Online, I can subtitle my words on the go.”

Students wearing face masks are also “harder to hear in large teaching spaces for social distancing,” says a humanities professor. “On the other hand, students unanimously tell me they prefer face-to-face, no matter what the health and safety conditions. And, in the end, it is their experience that matters most here.”

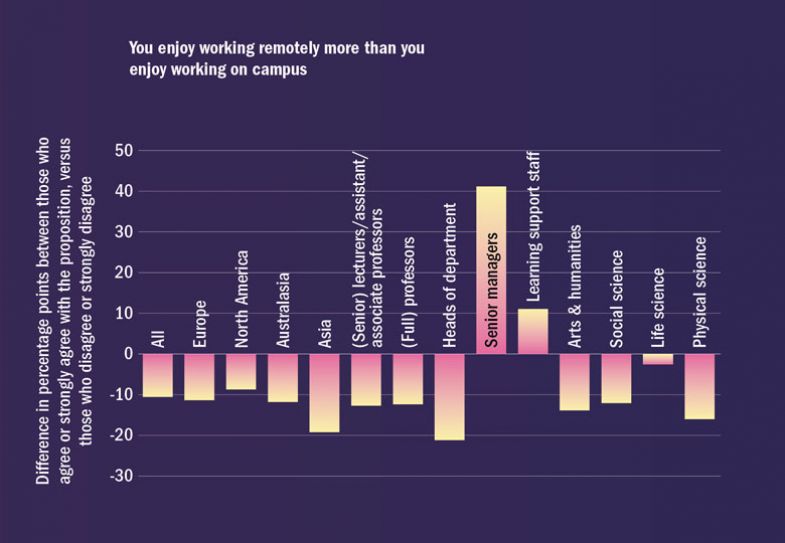

What about after Covid? Would respondents prefer to continue to work remotely? In general, the answer is no. Overall, 34 per cent would prefer to do so, against 45 per cent who would not. But opinions vary considerably, with life sciences academics roughly evenly split, learning support staff favouring remote working by 11 percentage points and senior managers by a huge 41 per cent.

Several respondents appreciate the reduced need to travel. “I don’t think I can go back to a commute with the same frequency as before,” says a social sciences lecturer. A humanities lecturer appreciates being “away from toxic colleagues”. And the careers education head of department appreciates “the quiet. The calm”.

However, a senior lecturer in social science is “sick of hearing people from wealthy backgrounds who live in big houses talk about how great [working from home] is. Some of us are struggling in unsuitable spaces, in cold houses, with bad wi-fi. Not all of us can afford the book-lined study.”

A senior lecturer in the life sciences also enjoys their campus’ “fast, reliable internet” as well as the “division between my work and home life. I also find that I am more active being at work than I am at home – cycling in to work and basic moving around campus to get a coffee etc – which significantly helps my mental health.”

A business lecturer in Australia regularly worked from home before the pandemic. But being forced to do so for long periods “has been a disaster for my motivation and my physical wellbeing”. And while an environmental sciences professor appreciates “having control of my workspace and time” they find that the lack of “interaction with colleagues in teaching and research is a big hole”.

Moreover, while remote working per se might be fine, several respondents repeat that remote teaching is not. “Too many students do not use their video: it is an awful experience talking to a wall of black boxes,” says a life sciences lecturer.

Overall, however, when asked which aspects of the digital switch should be retained regardless of Covid-related requirements, more than half of respondents (54 per cent) mention online lectures. Indeed, it is the second most popular answer, after online meetings (76 per cent). Online conferences, alternative assessment practices and the greater ability to intermingle professional commitments with personal ones are also appreciated by more than half of respondents, while online seminars, exams and lab classes are less popular.

However fiery the online baptism may have been for universities and their staff, it seems that some aspects of working practices may have been re-forged for the long term.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The great move on line

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login