Aleksandr Kogan knows all too well how a tie-up between academia and the tech world can go very, very wrong.

He is the University of Cambridge neuroscientist who earlier this year achieved international infamy for passing on Facebook profile data from tens of millions of users to the parent company of Cambridge Analytica, the now-defunct political consultancy accused of using this information to target potential Donald Trump voters in the 2016 US presidential election (something the firm has denied).

Now living in New York and working on a new online survey tool, Kogan acknowledges that the bad publicity has in effect ended his academic career. “I completely missed how people were going to react,” he says.

For some, this might sound like just deserts. Kogan used a Facebook app to harvest profile data from not only those who installed the app but their unwitting Facebook friends, too (something no longer possible after Facebook changed its rules in 2014). Some reports have suggested that his colleagues thought that what he was doing was unethical; Kogan had an application to use the data for academic purposes rejected in 2015 over concerns about consent.

As Kogan tells it, he was naive – but not greedy or ethically lax. He says he did not personally gain financially from his Cambridge Analytica deal, but simply wanted more funding to help gather a juicy research database from the world’s biggest social network. He had “no inkling” anyone would be upset.

“All this seems unbelievable and silly now, but from that vantage point it seemed sensible,” he says. “I’m a sceptical scientist [but] not a sceptical person.”

Neither his manager nor colleagues raised ethical objections to the tie-up, Kogan insists (a Cambridge spokesman said he could not comment as this would constitute personal information). “The university is very encouraging of its faculty members to go and do entrepreneurial activity,” partly as a way to hit impact targets in the research excellence framework, he adds.

Yet Kogan’s “entrepreneurial activity” culminated in denunciation of the university on the biggest stage possible. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, called before the US Congress after the scandal blew up in April, asked “whether there is something bad going on at Cambridge University overall that will require a stronger action from us”.

Earlier this month, the UK’s data protection watchdog, the Information Commissioner’s Office, revealed that it is investigating whether Kogan has committed a criminal offence. It announced that it is to audit the Cambridge Psychometrics Centre, where Kogan worked, for compliance with the Data Protection Act. The ICO is also to carry out, with Universities UK, a broader review of academics’ use of personal data, in both their research and commercial capacities. And the office has fined Facebook the maximum possible £500,000 over its part in the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In response to Zuckerberg’s question, Cambridge pointed out that it had worked for years on publicly available research that used Facebook data, including studies co-authored by Facebook employees. Kogan's venture is only one example - and one that went most specularly wrong - of a tie-up between academia and big tech. Earlier this year, for example, France’s École Polytechnique announced a new chair in artificial intelligence – funded by Google.

But the Cambridge Analytica scandal is just one instance of the “ techlash ” that many observers consider to be under way against the likes of Google, Facebook, Uber and Amazon. Silicon Valley’s finest stand accused of a litany of failings, including providing a platform for Russian interference in foreign elections, monopolistic behaviour, workforce exploitation – and simply making us feel miserable through the relentless interpersonal comparisons facilitated by social media. “ There’s Blood In The Water In Silicon Valley ” ran one headline on Buzzfeed late last year.

So should reputation-conscious universities reassess how they work with Big Tech?

James Williams has worked on both sides of the fence. A former Google advertising strategist, he is now a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford’s Oxford Internet Institute. His new book, Stand Out of Our Light, warns that Silicon Valley’s tools of distraction risk undermining our personal and collective will and freedom.

Williams thinks that researchers and universities that are funded by tech firms, or dependent on their data, are yet to apply the same “sensitivity” over conflicts of interest that is normal in, say, pharmaceutical research. “There is a sexiness to tech companies that’s obscured these questions of the power dynamics,” he says.

One of the earliest examples of the relationship turning sour came in 2014, with the publication of a study, authored by researchers from Facebook and Cornell University, that involved manipulating the moods of more than 600,000 Facebook users by exposing them to positive or negative emotions. The study, “Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion Through Social Networks”, published in PNAS, constituted a huge experiment on subjects whose consent was not sought, and triggered a major backlash against Facebook, the university and the journal.

Kogan, who collaborated with the social network until 2015, says that “Facebook has data that can answer any question I’m interested in”. But he recalls that the social network became “increasingly conservative” about working on academic papers in the wake of the reaction to the PNAS study. “That paper gave [them] so much negative attention that they clamped down hard on anything being published,” he says.

Now, following the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook is introducing further restrictions. Previously, academics could gather anonymous data about user behaviour, but Facebook is “shutting [that] completely down”, according to Anja Bechmann, an associate professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, who studies social media and artificial intelligence and is one of dozens of academics to sign a letter earlier this year warning that the changes will stymie academic research.

“If we want data, we have to work with [Facebook] directly”, Bechmann says. The fear is that “only the lucky few” will be permitted to do so: namely, the most prominent scholars from the most famous universities – and primarily those based in the US. Facebook will in effect be able to “choose the assigned research and research question and team”, she warns.

This is particularly unfortunate since, as social life has moved online, social media offers a much richer dataset than things such as traditional censuses for social science research, says Bechmann – who has compiled a lengthy list of publications that she says could not have existed without access to social media “application programming interfaces” (APIs), which third parties use to glean data from these sites.

“It’s not good for democracy or our understanding of society that [the public] don’t have access to research on [social media] data,” she says.

Facebook did not respond to questions from THE.

The issue of access to data goes wider than social media companies, however. For instance, the race is on in Silicon Valley to create safe, reliable self-driving cars – to which end, companies like Google and Uber have amassed mountains of street-level images and scans from roving test cars in order to teach self-learning artificial intelligence how to deal with every conceivable situation on the road.

This data – a potential treasure trove – “is being held on to very carefully” by the companies that collect it, says Andrew Moore, dean of Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Computer Science, despite a recommendation from the Obama administration that it should be made publicly available.

But in other data-heavy areas, researchers don’t need a relationship with a tech company, Moore points out – medical data, say, comes from teaching hospitals. And nine in 10 Carnegie Mellon academics are “quite satisfied” with the access they have to big data, he says: “We get approached very frequently by companies who want us to help them with large amounts of data, as opposed to us going out begging for data and the companies saying no.”

But Carnegie Mellon has suffered its own tech-related headaches. In 2015, Uber left Moore’s department “scrambling to recover” after tempting 40 academics and technicians away with huge salary bumps to form a lab in Pittsburg, The Wall Street Journal reported. There was a “tough period of three weeks when we were trying to figure out how we are going to move forward with our research”, Moore said at the time. Defections have continued to occur: earlier this year, for example, the department lost Manuela Veloso, head of machine learning technology, to financial services company JPMorgan Chase.

Stemming this tide of researchers to the tech world has become a big issue for universities, particularly in hyped, lucrative areas like artificial intelligence. It was a key concern of a recent national AI report released in France, which recommended – highly optimistically, as one of the authors admitted – doubling the salaries of graduate students in this area to stop them leaving.

Moore, who himself worked at Google for eight years, describes his job as “like managing a sports team. You’re going to be recruiting many folks, but you don’t expect them to stick around forever”. His main strategy for recruitment and retention is to appeal to researchers’ idealism. It remains easier, typically, to change society for the better in an academic rather than a corporate position, he says. For instance, computer science researchers at Carnegie Mellon have created an online tool that scans online adverts to detect and identify sex traffickers in the US, facilitating “almost daily arrests”. That is “incredibly rewarding” for the academics behind it, Moore says.

And while corporate researchers may not have to write government grant proposals, nor do they have access to unlimited resources. “The sadness is that you see them getting really excited about getting hold of a single intern for three months in the summer – whereas professors get to work with five to 10 graduate students,” Moore notes.

Still, in many cases, working for a big tech company can be the best way to get a new tool into the public domain, he admits. “It’s not just the data, but the access to the channels to take an idea and get it released to millions of users. That is very exciting.”

Then there is the money question. Last November, The Guardian reported on fears among AI researchers that “the crème de la crème of academia has been bought” by Silicon Valley. In one case, for instance, Apple convinced a PhD student at Imperial College London to drop their studies for a six-figure salary.

Nor is that crème de la crème confined to technological fields. Tech firms have also taken to hiring university economists. According to Susan Athey, professor of the economics of technology at Stanford University, this is not only because they want to better understand the complexities of online markets, but also because they feel a need to counter the looming threat of anti-monopoly regulation. “In-house economists can directly inform regulators and also help outside economic experts learn about the institutional facts, access data and become informed”, Athey has written. “Every week, I am contacted to help fill a position, or I hear about a new hire by firms like Airbnb, Netflix, [music streaming service] Pandora or Uber.”

But it remains computer scientists that tech firms most crave. According to Moore, researchers with experience of building autonomous systems – such as robots that can work underground – number in the “few hundreds” globally, and are consequently like “gold dust” to companies. Moving to a tech company nets such people a compensation package three to five times what they could earn at a university.

The result is that in a faculty of around 200, Moore loses 10-15 people a year to industry, with only around five coming the other way. This has required him to hire about 50 new academics in the past three years. His point to his recruits is that they should see the revolving door as a plus: “You can do these round trips,” he tells them.

But is a revolving door really a healthy state of affairs? Writing in The New York Times last year, the data scientist Cathy O’Neil warned that one consequence is that “professors working in computer science and robotics departments – or law schools – often find themselves in situations in which positing any sceptical message about technology could present a professional conflict of interest”. For this reason, academia is “asleep at the wheel” when it comes to warning lawmakers about tech’s downsides, she added.

Her article attracted strong rebuttals on social media, particularly from academics in the humanities and social sciences, who pointed to their often robust criticism of tech firms. But Moore admits that the revolving door does indeed create “somewhat of a conflict of interest”.

“I don’t think I would ever come out and make statements against a specific company – unless, of course, I knew it was doing something really bad,” he admits. “But if a company frustrated me in a particular month, or something like that, it does not make good business sense to moan about it publicly because usually it’s part of a bigger relationship.”

One option for academics who want to work for tech firms but also want to keep a foot in the academic world, are joint appointments. These have become increasingly common. Amazon’s chief economist, Patrick Bajari, is also professor of economics at the University of Washington, for instance. And in 2014, seven academics from Oxford’s computer science and engineering departments were recruited by DeepMind, a London-based AI company bought by Google in that same year and best known for creating a program capable of beating humans at the board game Go. Three of the academics – including Royal Society fellow Andrew Zisserman, a computer vision expert – also remained professors at Oxford. As part of the deal, Google also gave a “significant seven-figure sum” to their departments.

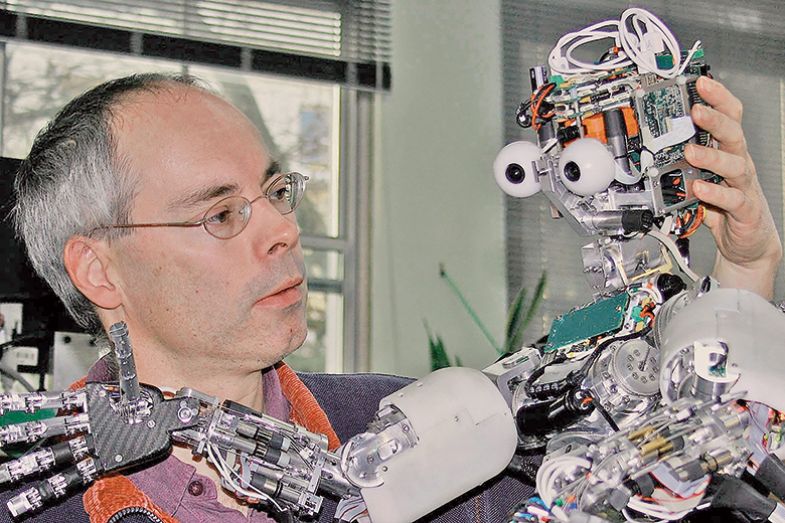

Bajari did not respond to a request for an interview. Times Higher Education also contacted the three DeepMind professors for an interview, but a spokeswoman for the comapny instead provided a statement from Murray Shanahan (pictured left), professor of cognitive robotics at Imperial College London, who is also a researcher at the firm. “The major incentive for me [in accepting a joint position] was the chance to pursue my research full time without the drain of other academic duties, with access to fabulous resources and in the company of the best like-minded people on the planet,” Shanahan says.

That motivation could be compared to that which attracted many academics to the fabled Bell Labs in the US, the corporate laboratory whose researchers won eight Nobel Prizes between 1937 and 2014. But are DeepMind researchers entirely free to choose what they research? The company’s spokeswoman says that the company does not “influence who researchers with dual affiliations collaborate with outside of DeepMind”. But she did not answer questions about whether there are any restrictions on what academics with joint affiliations can publish.

For his part, Shanahan admits that before he joined DeepMind, he “considered…the potential loss of freedom and independence I might experience from being part of a big corporation. Would I still be free to say and do what I liked (for example, to speak to the press) to the extent that I was as a full-time academic?” But after a year of working for the company, it is a case of “so far, so good”.

Moreover, despite being so potentially lucrative for big tech companies, machine learning and artificial intelligence have remained very open fields. Researchers were up in arms earlier this year, for instance, when Nature Publishing Group proposed a closed-access journal to serve the discipline. “The general advantages of being open about research in this area outweigh the potential or perceived advantages of being secretive,” says Zoubin Ghahramani, a professor of information engineering at Cambridge and chief scientist at Uber (the increasing demands of the latter role requiring him to relocate from Cambridge to San Francisco in August).

“Of course, Uber is a company, and so we have to be careful with respect to any commercially sensitive information,” he says. “So obviously we wouldn’t want to publish our business practices, which other companies might be very interested in, and we have to be careful about other things like IP and so on. But the norm…is in favour of openness.”

In the development of self-driving cars, “very little even in this field is about having a particular secret sauce for something”, he argues. “It’s not like one research paper is going to make a huge difference” as to whether one company wins the race to build a reliable vehicle.

But some remain troubled by the potential ethical compromises to which joint appointments could expose academics. This is particularly the case in Germany, where such positions remain hotly contested. The country is keen not to be left behind when it comes to artificial intelligence, and has created a “Cyber Valley” near Stuttgart that brings together university researchers and companies. And Martin Stratmann, president of the Max Planck Society, Germany’s vast basic research network, explains that it has hired heavily from the US to bring in directors for the Institute for Intelligent Systems, founded in 2011, that constitutes the “nucleus” of the project.

But he is dead set against allowing his academics to work for more than one master. “In the Max Planck Society…we do not have joint appointments,” he says. “We want to define our own rules. We have our own ethics rules. We have our own ethics councils – so we decide where to go.”

But others dispute that the ethical strains potentially imposed by joint positions with tech firms are uniquely acute. Uber is currently facing questions over an incident earlier this year in which one of its prototype self-driving cars – carrying a human observer – hit and killed a woman crossing the road in Arizona. So what would Cambridge’s Ghahramani do if he felt the company was rushing out a solution before it was safe?

“If something didn’t match my ethical standards, I would speak out,” he insists. “I think this is the role of whistleblowers in any kind of situation.”

DeepMind’s Shanahan also denies that “having a joint appointment puts me in a different position to any employee of any company or organisation”. Moreover, he does not expect to be confronted by any particularly serious ethical conflicts in his current role.

“One of the reasons I’m comfortable working at DeepMind is that there is a strong ethical ethos to the company,” he says. “So I don’t anticipate having to face such a moral dilemma.”

Campus, Inc: should universities venture into building businesses?

When the London tech start-up Magic Pony was sold for a reported $150 million (£102 million) to Twitter in June 2016, just 18 months after it was created, City investors sat up.

Admittedly, it wasn’t quite the jaw-dropping levels of profit enjoyed by Instagram founder Kevin Systrom, who sold up to Facebook for $1 billion in 2012 after a year of business, but it was further evidence that the UK capital was a growing rival to Silicon Valley for machine learning (Magic Pony uses neural networks to enhance images), following the sale of predictive text company SwiftKey to Microsoft for £174 million months earlier and DeepMind to Google for £400 million in 2014.

While Magic Pony’s founders, Rob Bishop and Zehan Wang, were graduates of Imperial College London, they did not fit the familiar “university pals strike it rich” narrative of Google or Facebook. They met at Entrepreneur First, a business incubator based in south London that seeks to bring together the brightest minds to see if they can come up with businesses that will fly.

“It’s a pretty unique model,” believes Joe White, the company’s chief financial officer, who joined in 2016 having sold Moonfruit, the website building company he co-founded just after graduating from the University of Cambridge, for $40 million in 2014.

“We’re sometimes conflated with traditional incubators as our output is similar. The difference is that we bring people together pre-team, pre-idea,” White explains. The 100 recruits in each cohort are offered a £2,000-a-month stipend for their first three months, as they set up their companies and develop investment pitches. The 20 or so businesses that look the most promising are then given £80,000 and a further three months of support – including mentoring from successful entrepreneurs and introductions to potential investors and customers – in return for an 8 per cent stake.

Recruits are typically in their mid- to late twenties, and are often PhD students or postdocs. “They have to have an edge,” explains White, and “a deep specialist knowledge” is an obvious example of one. A recent team, for instance, paired a graduate of a PhD in black holes with someone from the finance world to create an AI financial adviser.

That company has already attracted £1.6 million in venture capital investment. And with 10 London and three Singapore cohorts now complete, Entrepreneur First has developed companies with a total combined value of £1.5 billion, which have raised more than £300 million from venture capitalists, White says.

Yet the company’s heavy reliance on university talent raises the question of whether this is the type of thing UK universities and business schools should be doing themselves. Could such a blurring of the university and tech worlds be one way for them to maintain a connection with their most promising early career researchers in computer science, while also tapping into the vast amounts of money to be made in the tech world?

White demurs. “Universities, like many industries, get good at doing a certain thing. They are very good at educating and producing world-class research, [but] the venture capital world is at odds with this environment, so having these things operating beside each other is very difficult.”

For him, universities should confine their involvement with the tech world to investing some of their endowments in it. He cites Stanford University’s lucrative investment in Sequoia Capital, early investors in PayPal, Google and WhatsApp – although he concedes that few UK universities have remotely comparable amounts of capital to play with.

White also cautions against universities’ preference for what he calls the “intellectual property bear hug”, whereby they “grab hold of anything that looks promising”, taking large ownership stakes in the spin-off company and thereby “stifling” its further growth. In a recent example, a nascent tech company struggled to win seed funding because the PhD student who ran it had given up a 50 per cent share to his institution. The investment was secured only after the university reduced its share to 10 per cent.

“[The PhD student] was a researcher, not an entrepreneur, so didn’t understand the deal at the time,” White says. “But it meant his idea wasn’t going to get off the ground – investors won’t back something if so much has been given away. [For universities], it’s better to have 10 per cent of something that becomes massive, than 50 per cent of not very much at all.”

Jack Grove

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How green is the valley?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login