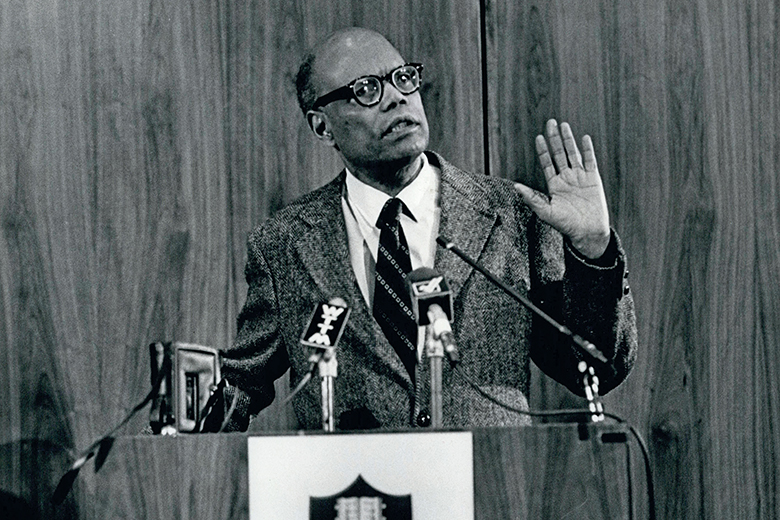

Arthur Lewis spoke to the curious child with a deep interest in people and the lives they lead

My first loves were photography, writing and economics, in that chronological order.

I had a camera from the age of five, and since I had no younger siblings to frog-march around, I used to line up my teddy bears as models.

As a teenager, I would spend hours in my own world, scribbling tales about people and lives created in my imagination.

My interest in economics began later, with family holidays to my parents’ homeland of Dominica. I found it intriguing how you could jump on a plane and, eight hours later, be in a different world. The fascination grew when I visited Guyana in 1990. At the time, the weak Guyanese dollar meant that the country’s largest note had the spending power of a 50 pence piece. That could buy you the best theatre seat in Georgetown. I remember riding the bus there and realising that I could not convert the fare into pounds because we didn’t have a coin that small.

But my formal study of economics began – as with many things in life – as a total accident. I wasn’t happy that physics was being taught at a partner school, so I decided to switch subjects.

I remember our sixth-form tutor telling me that no girl had ever got higher than a C grade in economics. Already used to breaking the mould, I was undeterred, and ended up with an A – even if my other subjects needed resitting before I could move on to the university of my choice.

That was when I came across the St Lucian economist Arthur Lewis. I found him and his work inspirational. It was the first time in my formal education that I was learning about ideas posited by a black man: someone like me, who had done and said something others thought was important.

I knew St Lucia: it was an island hop away from Dominica. And I felt a sense of pride as I studied the renowned “Lewis model of surplus labour”, which many scholars still apply to China. For me, Lewis – who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1979 – was a role model, reinforcing the sense that I could make a valuable contribution to economics.

He also wrote about development issues, addressing my earliest economic questions. He spoke to the curious child with a deep interest in people and the lives they lead – be it by capturing a special moment on camera, writing fiction or trying to understand why exchange rates in Guyana refused to tend towards purchasing power parity.

Karen St.Jean-Kufuor is a principal lecturer in economics and quantitative methods at the University of Westminster.

I loved the way that Nancy Drew untangled puzzles but I wasn’t sure what kind of job would allow me to do the same

When I was young girl, I didn’t really know what a university was. Perhaps because it was assumed that I would go to one, no one bothered to explain why I would want to. I knew some academics, but what they did was deeply mysterious. It certainly never occurred to me that I might one day join their ranks.

But I was always a bookish sort. The original Nancy Drew mysteries were my favourites when I was eight years old, even though their dated and often classist and racist tone was obvious even to a child reader. The stories made it acceptable to be smart, competent, and inquisitive, qualities that were not supported in my local environment, where sports tended to dominate.

I loved the way that Nancy untangled puzzles, particularly about how people thought, but I wasn’t sure what kind of job might allow me to do the same. Growing up in post-riot Detroit in the late 1960s and early 1970s had put me off being a detective or policewoman for life.

Perhaps most appealing was Nancy’s independence and lack of need for adult supervision. Although her affluence allowed her freedom that I could not even imagine, I sensed that there was a wider world in which I might thrive. I was increasingly intrigued by science, but classes at school were uninteresting given their dominant focus on correct answers rather than enquiry.

During my teenage years, I volunteered at hospitals to help others, thinking that a clinical career might be ideal. Genetics became a special focus because many questions remained unsolved even though the underlying principles were logical and deductive.

But I kept returning to my interests in figuring out how things came to be the way they were, and how people came to know what they knew: only later did I realise that these were the academic fields known as history and philosophy. I chose my college randomly, based on its long distance from home, extremely small student body and lack of a requirement to pick a major. Yet I was fortunate that its Great Books curriculum, encompassing Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes and many other classics, allowed me to keep studying everything, with others who were equally motivated – including our teachers.

Later, while working in publishing, a couple of our authors alerted me to the fact that there was a field called history and philosophy of science, and that a PhD would allow me to be a researcher and teacher for life.

Who knows what Nancy would have become when she grew up. It is likely that her father would have encouraged her to follow in his footsteps into a lucrative and prestigious but potentially dull career in law. But, as her biggest fan, I get to answer difficult questions and disentangle puzzles every day.

Rachel A. Ankeny is associate dean (research) at the University of Adelaide.

Dian Fossey’s unconventional methods hinted at the importance of women’s perspective in intellectual pursuits

When Sigourney Weaver played primatologist Dian Fossey in the 1988 Oscar-winning movie, Gorillas in the Mist, my teenage heart and mind were transfixed.

Although Hollywood felt it necessary to include a human love story in the film, the deepest love existed between Fossey and the Rwandan silverback gorillas. When researching these magnificent animals, she eschewed the previously undisputed rule that primatologists focus on groups, rather than individuals. Fossey came to know the gorillas as she had known the autistic children with whom she had once worked; she sat with them in their habitats, mimicked their sounds, ate their plants, played their games and gained their trust. Digit, whom she named because of his damaged finger, was her favourite.

As a teenage girl who babysat often, I related to Fossey’s nurturing approach. Her unconventional methods not only led to groundbreaking new insights that reshaped the field of primatology: they also hinted at the importance of girls’ and women’s participation and perspective in intellectual pursuits.

But, personally, I never envisioned falling in love with a smelly gorilla. And my own fascination with nature was more about the mathematical patterns it displayed: the sequential Fibonacci numbers you could see in sunflowers, pine cones, cacti and pineapples; the fractals that reveal themselves on coastlines, ferns, tree limbs and the human circulatory system.

I also spent inordinate amounts of time using mathematical techniques to make and break secret codes. I took time to get to know individual ciphers, including the Caesar shift cipher, the tic-tac-toe diagrammatic cipher and the book cipher. I sat with them on a rock wall in the woods behind my house, mimicking their patterns, digesting their lessons, playing their games and learning which to trust.

My favourite – my Digit – was my spin-on-a-scytale cipher, which involves a piece of paper wrapped around a cylindrical object. My modified scytale cipher required a bent stick that I found in the forest, ensuring that no enemy could decode my messages without that unique, natural key.

I did not envision becoming a mathematician in 1988 – a year when only 18 per cent of new US mathematics doctorates were earned by women. However, when I did take that path, I was bolstered by my memory of Fossey. Her legacy assured me that, as a young woman, I might nurture my interests and add an all-important new perspective to the field of mathematics.

Susan D’Agostino is an associate professor of mathematics at Southern New Hampshire University.

For the exposure to natural history that kindled an all-consuming passion, I have to thank not a person but a television series

When asked who my childhood heroes were, many obvious names sprang to mind.

How could a nascent biologist fail to be inspired by the genius of Charles Darwin or the brilliance of Thomas Huxley? I was also enthused by the books of Gerald Durrell and Desmond Morris, and by the kindness of Joyce Pope, the information officer at the Natural History Museum. Joyce unlocked hidden doors to reveal unseen treasures: most memorably, a drawer containing preserved finches from the Galapagos, collected and labelled by Darwin himself.

But these people, inspiring though they were, did not provide the sustained week-on-week exposure to natural history necessary to properly kindle an all-consuming passion. For that, I have to thank not a person but a television series.

I acknowledge that such an admission may be problematic. There remains the residual prejudice that television is not an entirely worthy conduit for knowledge and inspiration. But, for me, and I suspect many others, it worked a treat.

The World About Us began its run on BBC Two in 1967 and was the defining influence of my childhood years. The programmes were broadcast early on Sunday evenings, when invariably, my grandparents joined my parents and me for “Sunday tea”. Most of the episodes were fairly safe. Jacques Cousteau’s images of an underwater world always generated interest and enthusiasm across the age spectrum.

From time to time, however, the unsuspecting viewer would be confronted with naked tribespeople undertaking their various domestic duties. Swinging breasts would generate an excruciating silence in our house that could only be broken with a brusque offer of more trifle. Copulating lions and elephants had a similar effect.

However, the most memorable episode involved native people from the Papuan jungle. Along with a few feathers and wild hair, the men displayed impressive and decorative penis gourds, pressed firmly against their scrota. This was all very fascinating for a young boy, but less so for those born in the Edwardian era. I could sense that my repeated questions about these peculiar fruits of the loin were not appreciated, and that no amount of attempted distraction with custard, jelly and tinned peaches was going to restore the tranquillity of that particular Sunday tea.

It became clear to me that biology not only had the power to be inherently fascinating, but also had the muscle, as it were, to change human behaviour. And I became resolved to make my own contribution to it.

So there it is. But for those readers troubled by my wriggling out of the remit of this feature by failing to offer up a human hero, I have a compromise to offer. I have discovered during the preparation of this article that

The World About Us was, in fact, the product of a single remarkable and creative mind: the then commissioner of BBC Two, Sir David Attenborough.

So, although I didn’t know it at the time, it seems that one individual did after all provide a heroic influence upon my early years. And the fact that Attenborough went on, with his own landmark natural history programmes, to further unlock the educational and inspirational power of television makes him an especially apposite choice.

Russell Foster is professor of circadian neuroscience at the University of Oxford.

André Previn, the teen idol who lit up my past, continues to inhabit my present

As a trumpeter, my teen idols were unsurprising: Miles Davis, Swedish player Håkan Hardenberger and brass ensemble leader Philip Jones, who became a mentor.

Another idol – an early crush – was Brazilian pianist Cristina Ortiz. Her passionate and spontaneous interpretations of De Falla, Granados and Villa-Lobos could melt even the most phlegmatic of Brits and set them on an emotional rollercoaster.

But it was André Previn, the young, inspired conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, who stands above all others as an influence.

His was the high-fidelity, mellifluously Californian voiceover on André Previn’s Music Night, first broadcast on the BBC in 1971. Talking straight to camera, his animateur introductions gave millions of viewers their first glimpses into the world of classical music, and brought wide recognition to the works of Bernstein, Copland, Prokofiev and Rachmaninov.

His joshing with Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise further endeared him to me. At the time, he had apparently been worried that back and forth banter would make light of the music, but Morecambe’s remark that “I’m playing all the right notes – but not necessarily in the right order” became small screen history.

Later, through a Churchill fellowship to the Juilliard School in New York, I found myself invited to “do lunch with André” by some undergraduates at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. It was the first time I had heard the expression and wondered if we might be cooking with him. In a sense we were. Previn was due to conduct a new work by American composer Ned Rorem, so score preparation – committing a score to memory, learning its overall shape and structure, its essential cues and tonal centres – was de rigueur.

It was Previn’s remarkably protean, consummate musicianship that enabled him to interact with audiences so deftly. Underpinned by a jazz pianist’s instinctual flair and the ease of a natural communicator, he drew many modern-day conductorteachers to realise something of the versatile musician in themselves. In my case, he inspired a switch from dabbling in jazz and brooding, dark-hued brass band monotones of childhood to a chromatic colour-wheel orchestral palette.

Some years ago, the Shell LSO scholarship series presented the opportunity for me to work more closely with the London Symphony Orchestra, and more recently, I was able to renew connections with it during its Asian tour. London’s oldest orchestra proved as vibrant and connective under the direction of Daniel Harding as it was in Previn’s day.

Kit Thompson is master of Moon Chun Memorial College at the University of Macau and is a former principal of Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham City University. Prior to his appointment in Macau, he was director of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login