In a single generation, China’s previously stodgy and closed university system has been transformed into one whose most prominent members are producing world-class research and muscling into the upper echelons of global rankings.

Tsinghua University recently became the first Chinese institution to enter the top 20 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Fudan University and Zhejiang University also broke into the top 100, taking the number of Chinese institutions in that bracket to six – compared with only three 10 years earlier. The nation recently overtook the UK on an annual list of nations with the most highly cited scholars, published by Clarivate Analytics, putting it second behind the US. And China’s involvement in what Clarivate deems cutting-edge areas of science is now similar in scale to that of the US, particularly in physical science.

These achievements are the result of 20 years of reform, implemented via highly centralised government control. Top universities have been pushed to adopt corporate management styles ruthlessly focused on meeting key performance indicators such as research citation volumes and ranking positions. In return, they have been enrolled in a series of lucrative excellence initiatives that have seen their budgets mushroom.

China’s national higher education spend of RMB 1.3 trillion in 2019 (£154 billion) was a 12 per cent increase on the previous year alone, and a full 41 per cent increase since 2015. And while some belts were tightened and projects stalled during this year’s pandemic, it is unlikely that funding will drop significantly in the coming year. Indeed, China has already all but guaranteed funding for STEM research for the medium term via its latest five-year plan, which comes into force this year and will set the broad direction of Chinese government policy until 2025.

In the longer term, China is looking to match and even surpass Western rivals. In September, the Ministry of Education (MoE) issued guidelines for making China a postgraduate education powerhouse by 2035. And the country’s most recent excellence initiative, the Double First Class programme, has the stated goal of transforming participant institutions into truly world-leading institutions by 2050.

Yet any rapid and mass restructuring of a higher education system – much less the world’s largest – inevitably comes with downsides and resentments.

One of those relates to the fact that most of the reforms and extra funding are being concentrated at the top end of China’s highly stratified system: specifically, the 39 “Tier 1” universities and the 73 “Tier 2” institutions. The remaining 1,124 Tier 3 institutions have not been given the same privileges. For example, while hiring rules are being loosened across the board – all universities now can appoint associate or full professors without consulting the ministry – there is far more leeway for those in the upper tiers, especially around recruitment of foreign staff and students.

For those academics at the coalface of Tier 1 and 2 universities, though, the reforms are more of a mixed blessing. According to Fei Shu, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Science and Education Evaluation at Hangzhou Dianzi University, while Tier 3 institutions still largely hold on to China’s traditional “iron rice bowl” mentality, according to which scholars are all but guaranteed job security for life regardless of how they perform, those at higher-ranked institutions have been thrust into the white heat of a “publish or perish” culture.

One mechanism by which this pressure is applied is the tenure track system that has been introduced, at governmental stipulation, at Double First Class institutions.

“Every [top] university plays the university ranking game,” Shu says. “They know the criteria and adjust their assessment policies to maximise their scores in these criteria.” And this is reflected in their criteria for granting tenure. Last year, Shu co-authored a study on the role of Web of Science publications in tenure policy at 75 Chinese universities, published in Scientometrics, which shows the disproportionately heavy weight given to citations.

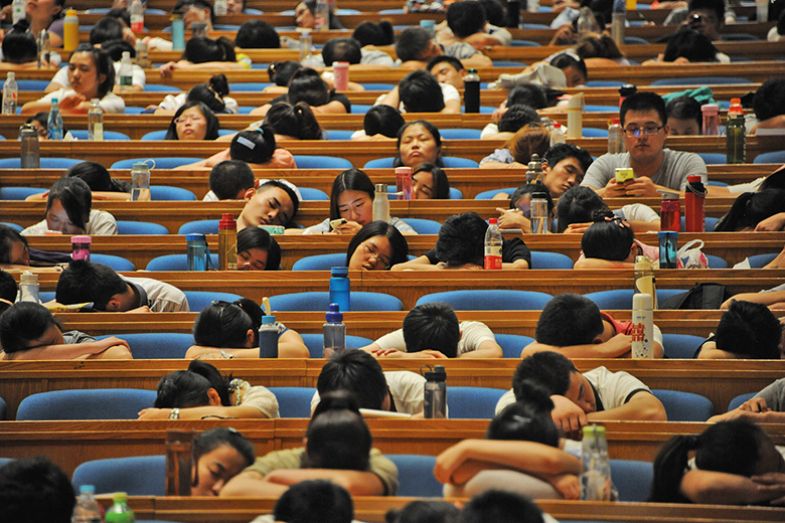

Indeed, the Chinese system is unique in that bibliometric indicators alone can be enough to obtain tenure. “A young scholar could be tenured with an excellent research record without any teaching; but it does not work in reverse,” Shu explains. As a result, “over the past 20 years, tenure policies have helped develop the research excellence of China’s higher education, but at the expense of the quality of teaching and service.”

The challenge, he says, is to “keep a balance between research and other criteria. It is acceptable that research is weighted more in the tenure evaluation, but what is the limit? In my view, research should be weighted at a maximum of 50 per cent, but, in reality, it is weighted at more than 80 per cent in most cases.”

Shu is particularly worried by the narrow, numerical focus of research evaluation in China. “Administrators like numbers since all university rankings are based on numbers,” he says. But the risk is that “the purpose of research in China becomes not to advance knowledge, but to pursue numbers”.

Moreover, such a pursuit offers a huge incentive for academics to attempt to game the numbers. There has been some recent soul-searching in China about how to address endemic problems such as unethical behaviour and questionable research, leading the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) recently to implement new rules on research misconduct, in particular targeting “paper mills” that sell low-quality research papers to less-than-scrupulous academics to boost their publication metrics.

Rui Yang, associate dean (research) in the education faculty of the University of Hong Kong (HKU) and a specialist in cross-cultural analyses of education systems, notes that “even highly sophisticated higher education systems, like in the US and northern Europe, have been hugely affected by ‘audit culture’”. However, the difference is that since the West developed this culture over decades, checks and balances emerged that are not present in China.

“China was keen to learn from international experience, but it does not have the same counter-forces,” he says. “For example, in the West, teachers’ unions are very powerful and can fight for academics’ rights. The original tenure system [in the West] was supposed to protect academic freedom, not push people to publish more. But now it’s being used in East Asia as a stick, not a carrot.”

His argument is echoed by Yang Shen, an associate professor at Shanghai Jiaotong University who studies gender issues. She says that few Chinese universities have, for instance, introduced “stop-the-tenure-clock” policies to help protect the careers of pregnant women and those who take parental leave. “The lack of family-friendly policies may contribute to academics’ high work pressure, especially women academics,” she says.

Shen co-authored a study published in September in Studies in Higher Education showing that female Chinese academics on fixed-term, pre-tenure contracts are twice as likely to change their childbearing plans because of work considerations as those who are already tenured. According to one respondent, since the tenure track was introduced at her institution, no female employee on a fixed-term contract has given birth.

But Shen adds that the gender implications of the tenure track system are only one part of a larger discussion. “There is an ongoing, heated debate in China about the meaning and the future of higher education and academic research,” she says.

HKU’s Yang hopes that this discussion leads to change in the coming years. “Fast development leads to a very top-down management style,” he says. “But, sooner or later, Chinese higher education will need to change from rough, quantitative growth to real, high-quality development. Managing academic work is much more difficult than managing a business, where your main goal is just money. For managing academics, you need to take into account emotions, dignity and creativity.”

Another concern with China’s focus on citations is that it may narrow the nation’s disciplinary breadth. A recent study in the East China Normal University Review of Education, for instance, found that Chinese academics were inclined to write about topics popular with journal editors, rather than ones most relevant or useful to Chinese society.

According to Futao Huang, a professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, China’s push to boost the international prominence of its universities has meant that “teaching quality, especially teaching undergraduate activities, and research on non-STEM fields were not sufficiently emphasised or highly valued.”

This has led to some humanities and social science faculties, departments and research institutes being closed, or suffering from staff cuts. However, Huang feels that the issue is being addressed. “The Chinese government has implemented some strategies to reform evaluation systems in relation to the academic performance of individual academics, and also individual universities, by introducing more diverse indicators,” he says.

Even MOST and the MoE admitted to presiding over a “one-sided, excessive and distorted reliance on [Science Citation Index] papers in current scientific research evaluation”, in a 2020 statement. In December, the MoE released new guidelines on academic assessment for philosophy and the social sciences stressing that achievement should be assessed on a comprehensive matrix, as opposed to merely counting papers; similar guidance for assessing science and technology research was issued by MOST in February. In a similar vein, Beijing’s Renmin University has established a new Evaluation Research Centre to explore how assessments can “truly reflect” academic quality, in collaboration with other Chinese universities.

The allocation of resources among Chinese universities is also being questioned by some.

As in all countries, highly ranked and outward-facing universities receive the lion’s share of funding – particularly for programmes that align with national goals, such as fighting Covid or producing industry-friendly technology. Large recent investments include a new public health school at Tsinghua, headed by a former World Health Organisation director-general and bankrolled by Vanke, a property giant with close state ties. In November, NYU Shanghai opened a Centre for Applied Social and Economic Research, whose first project was about Covid. And that same month, the Anglo-Chinese joint venture Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) opened a new pharmacy school.

Youmin Xi, XJTLU’s executive president, says that while all the new funding is welcome and will fuel the rise of Chinese universities, care also has to be taken that resources are well used across the country.

“The government needs to pay serious attention to reforming resource allocation and also evaluation procedures,” he says. Otherwise, he fears too many universities may chase government priorities regardless of whether it makes sense for them institutionally, leaving the country with too much provision in those areas and too little elsewhere.

Xi also thinks that to genuinely improve their quality, China’s universities need a more flexible approach to their teaching, allowing them, for instance, to embrace lifelong learning. But they could be careful about becoming too vocationally focused, he adds, especially in research.

“In terms of long-term, sustainable development, we still need to push universities to focus on basic research, which may take several years or even decades to generate new ideas with a disruptive effect on society,” Xi says. “That’s a key function of a university.”

China’s spending on basic research currently amounts to 0.12 per cent of GDP: below that of competitor nations such as the US (0.47 per cent) and Japan (0.41 per cent), and it appears that the government agrees that this is too low. Speaking in December, Premier Li Keqiang was reported by the Xinhua news agency to have said that “while making optimal use of government funds, universities, research institutes, enterprises and private sectors should also be encouraged to increase investment in basic research”. He also pledged “to deepen the reform of streamlining administrative approvals, delegating power to lower levels, improving regulations, and upgrading services, with aims to encourage scientists and researchers to be more devoted to and creative in their work”.

Experts regard greater international engagement as another step that China needs to take if it is to improve further. The number of students it sends abroad has famously mushroomed, and international enrolments in its own system have also doubled over the past decade, reaching nearly half a million. However, foreign students still make up less than 1 per cent of China’s total student body, and they can only enrol in institutions with special permission to accept foreigners. Currently, they are all locked out of the country entirely owing to strict pandemic-related border closures.

Those that Times Higher Education spoke to for this article agree that while Chinese institutions might engage in more global outreach, the control of overseas activity by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is unlikely to be loosened any time soon – particularly amid rising tensions with the likes of the US and Australia over security issues.

Hiroshima’s Huang says there are specific types of intelligence that China wants to import: institutional governance and management practices; high-quality course content that Chinese universities cannot provide; and cutting-edge research in emerging STEM disciplines, mostly via “star professors”.

Hongqing Yang, a doctoral candidate at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, predicts that returning Chinese and foreign academics are likely to be drawn to China over the coming years by “the growth of job opportunities in China and fewer opportunities abroad for political and economic reasons”, and will bring with them “new ideas for teaching, research and assessments”. But he too doubts that the presence of the CCP will be less keenly felt even on the campuses of joint venture universities, of which Nottingham’s was the first to open in 2004. Yang, who has worked at three international branch campuses in China, says that one of the country’s rationales for opening such campuses is “to promote reform of education”, but he emphasises that while they have greater latitude in management, the state still keeps a careful ideological eye on them.

Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at SOAS University of London, points out that China’s recent rise in university rankings – partly driven by its greater international ties – “coincided with tightening of control on Chinese campuses under Xi Jinping”. Curricula in subjects such as modern history, politics and journalism remain scrubbed clean of controversial topics, while the Great Firewall means that the average student or scholar cannot access some global online resources unless they have access to a virtual private network (VPN).

In December, Chen Wenling, a chief economist at government-backed thinktank the China Centre for International Economic Exchange, made a rare public call for academics to be given more leeway to speak their minds and take risks.

“The system should tolerate mistakes and allow various ways of expression among experts,” she told a panel on making China into an ideological powerhouse, according to the South China Morning Post’s translation. “Some [government] departments even ask everyone – even those from academia – to stick with the same narrative. The system should allow mistakes, trial and error, and corrections. We are talking about tolerance to the world. Why can’t we be more tolerant to our academics?”

She added that the “many top scientists, talents and experts” that China has attracted “need a free flow of data for instant understanding of the happenings in the world”.

Tsang agrees: “Mediocre universities can manage without international ties. Top ones cannot,” he says. “For all the ranking achievements of the top universities, first-rate scholars outside of China know the realities on the ground in their partner institutions in China. In the social sciences, the scope of cooperation is narrowing fast.”

So how high can China reasonably expect to fly?

There are two relevant questions that often come up in Chinese higher education circles. One is when a scientific Nobel Prize will go to an expert who was born, educated and based in mainland China, as opposed to those who pursued their careers overseas. The second is if, or when, a Chinese university will be comparable to Harvard University.

Right now, some experts are sceptical that the latter aspiration can be fulfilled, as the Double First Class programme demands. According to one Chinese professor, who does not want to be named: “In mainland China, you will never find a Harvard if the fundamental values [of academic freedom] are absent.” Tsang agrees. Nor does he think that a Chinese Harvard could be recognised via rankings alone. “A ranking merely shows how universities perform by certain specific metrics,” he says. “It does not…confirm a university as among the very best in the world.”

Hiroshima’s Huang also believes that institutional autonomy and academic freedom are prerequisites for a Chinese Harvard. There is currently “a lack of an academic atmosphere where academics or scientists can foster graduates with critical thinking and innovative ideas or capabilities…Because of this, it is extremely difficult for Chinese universities to attract a large number of top academics – especially those in humanities and social sciences – let alone produce [domestically a significant] number of globally recognised talents.”

Hamish Coates, director of the Higher Education Research Division at Tsinghua, notes that “creating world-leading insights, particularly beyond STEM, requires superb academic structures, abundant resources and space for imaginative venturing”. However, he adds that China is already “moving to globally aligned, performance-oriented faculty workforce arrangements, while at the same time adding distinctive Chinese characteristics”.

That emphasis on Chinese characteristics is also raised by HKU’s Rui Yang. Simply cutting and pasting Western practices will not work in China, he believes.

“China has its own culture, history, society and politics – and that will play a role,” he says. “To find the answer to our problems, we do not need to travel to Massachusetts or California. Only we can find a solution to our own problems.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login