History is deeply contested in Hungary. Venture out into Budapest’s Liberty Square and one is immediately confronted by diverse political narratives. There is a shiny bronze statue of Ronald Reagan – sometimes celebrated in eastern Europe as the man who won the Cold War – walking very unnaturally, but there is also a monument to the Soviet liberation of the country after the Second World War. Even Admiral Horthy, who ruled Hungary from 1920 to 1944 – and ended up collaborating with the Nazis – is commemorated in a bust on the steps of a church.

Another recently erected monument pays tribute to the victims of the German occupation of 1944-45, most obviously the Jews who were deported and killed. Yet it has proved highly controversial, with critics claiming that it glosses over earlier Hungarian anti-Jewish legislation and the role of Hungarian collaborators in persecuting their own citizens. Some of those critics have created a set of poignant mini-shrines out of photographs and personal objects representing family memories of the Holocaust. More dramatically, in 2014, a performance artist called Victoria Mohos spent a quarter of an hour screaming at the monument.

All this is grist to the mill of Andrea Pető, professor in the department of gender studies at the Central European University (CEU), who recently received the 2018 All European Academies Madame de Staël Prize for Cultural Values. An expert on the politics of memory, she regularly takes students on her cultural heritage module to Liberty Square to examine how conflicting historical perspectives are on display. She also leads them on tours across the city, considering which people – and, particularly, which women – are (and are not) celebrated in public sculpture. During the tours, which are also open to all CEU students during orientation week, she describes the pioneering feminist organisations, the sites of orphanages and demonstrations, the roles women played in theatre and cabaret, the salonnières who created spaces for alternative ideas, and even the family who set up a crèche in the early 20th century where all the children were naked.

Such a tour could take place in many other cities, yet in today’s Hungary it has an extra dimension. Gender studies has never been securely implanted in eastern Europe, and populist governments committed to traditional family values have been very hostile. Viktor Orbán, prime minister from 1998 to 2002 and again since 2010, has often threatened the CEU and is active in promoting a particular vision of national history. Striking evidence for this can found in a macabre tourist attraction at what was once the most feared address in Budapest: 60 Andrássy Boulevard.

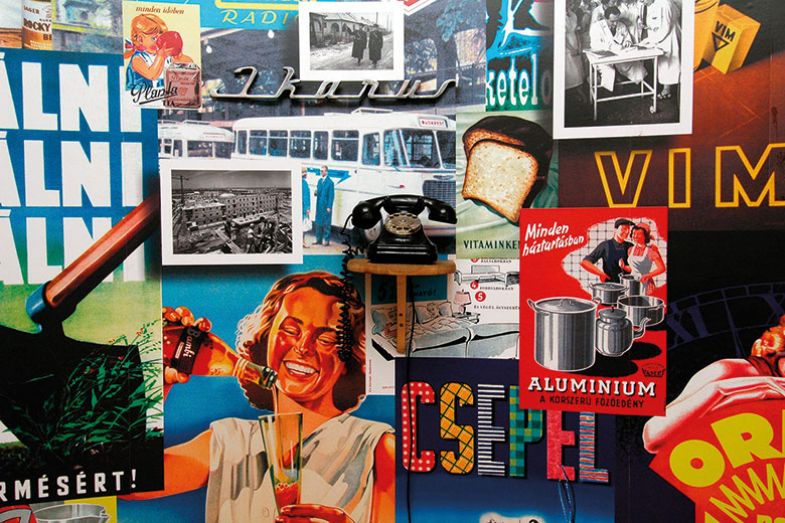

The headquarters of the Arrow Cross Party, the Hungarian Nazis who ran the country under part of the German occupation, the building was taken over by the political police during the Soviet era. Under both regimes, it was notorious as a place where many prisoners were tortured and often killed. In 2002, it was turned into a museum known as the House of Terror.

Although the cells in the basement are chilling, many of the exhibits feel manipulative in their use of melodramatic tableaux, harrowing testimonies and ominous music to promote a sense of the Hungarian population as eternal victims. The brochure makes clear that this strange chamber of horrors was created “with the support of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán” – in order, Pető asserts, to promote a contentiously plaintive view of Hungarian history.

“They are pushing their own reading of history,” she says. “That version has always been present, but not at the level of state policy…Previously the government wasn’t consciously and ruthlessly involved in memory politics. Now they are using the past and history for their own legitimisation and also for security. They are securitising history as a discipline: if you don’t have the right view of the past, you are becoming an enemy.”

So where does that leave someone such as Pető, whose work is strongly feminist and has often engaged with painful and sometimes taboo historical topics: the Holocaust, the “people’s tribunals” that delivered summary justice after the Second World War, the role of armed female fighters during the short-lived 1956 revolution and, most recently, the Hungarian women raped by the soldiers of the Red Army?

At the start of her career, Pető admits, she was tempted to turn away from the horrors and look at more cheerful topics.

Her extended family, she explains, “experienced different forms of discrimination: forced mobility, forced resettlement, imprisonment and deportation. That gave me a responsibility. The only thing my father told me not to do was to get involved in politics, because he was heavily involved in the 1956 revolution and wanted to save me from that. My first dissertation was about the English utopian movement. I really wanted to work on the Enlightenment and utopianism – I named my son after Oliver Cromwell!”

Yet, as time went on, Pető found herself drawn to “topics which successful mainstream historians say don’t exist!” In a formative episode in her mid-twenties, she told an established professor about the research for her first book, about the involvement of women in Hungarian politics after 1945. He responded: “That’s an easy topic, because it doesn’t exist!” That is when she realised how, “as a female academic, it’s very hard to work within the very traditional, hierarchical, feudal male society of historians. Even someone you believe is a friend doesn’t validate the years of work you’ve invested in a project. I will never forget that moment.”

As an ethical principle, Pető takes the view that silence can be “a form of resistance and self-preservation”, and that it is wrong for researchers to “push an interviewee to tell a story they do not want to tell”. Yet she is personally very committed to facing up to the darkest episodes of human history: “I always have questions, and they are always painful questions. You always have to ask the uncomfortable questions, which actually move us forward.”

When Pető began working on women in the Arrow Cross Party, for example, she once again came up against assertions that “they did not exist”. But “it turns out that in some constituencies, 30 per cent of the [party] members were women. Today, in the Hungarian Parliament, 10 per cent of members are women. So there was something there which actually mobilised women in the 1930s and 1940s, and if we don’t understand that, we will never understand why only 10 per cent of Hungarian MPs are women.”

The research behind Pető’s new book about the women raped by Soviet soldiers at the end of the Second World War, Telling the Untellable (currently only available in Hungarian), has certainly aroused some strong reactions.

On one occasion, while being interviewed on Swedish television, she “saw that the cameraman, who looked like a huge Viking, went pale, took off his headphones and left. I was talking about infanticide and the skeletons of babies found in eastern Poland in the forest. I was enthusiastic because [the research drew on] a new source, but this huge man could not take it and just left.”

Others have been unable to accept what Pető’s evidence might entail about the past conduct of members of their own families. She recalls a time, some years ago, when she was talking at a summer school for feminist activists in Ukraine about “the theoretical and methodological problems of interviewing the women who had been raped”. Her presentation was “greeted by a deathly silence, which had never happened to me before – and then one woman raised her hand and said: ‘My grandfather was a hero’. She went on to tell the family stories about her grandfather fighting from his Ukrainian village all the way to Berlin…It’s pretty obvious that, in that family, only those stories were acknowledged. They were the ones discussed around the table. There was no space to tell a different story.”

Strangely enough, Pető’s pioneering 1999 paper about the rapes became her “most quoted article” – particularly in the months of February and April, which mark the anniversary of the liberation of Budapest and the end of the war in Hungary. This is because it was taken up “on far right and conservative websites, where people cited the fact that a feminist historian was saying that massive numbers of rapes were committed by Red Army soldiers. My work was basically appropriated by those political groups, and interpreted simplistically as Russians raping Hungarian women.” Yet interpretations that look only at the ethnicity of the perpetrators and the victims, she argues in her new book, fail to “address the structural problem, that militarism necessarily makes women’s bodies accessible to victorious soldiers”.

More generally, Pető makes the powerful claim that “you cannot really write a history of the Second World War without addressing the massive atrocities committed against women. And this was basically missing from the history of the war, or it was addressed at the anecdotal, individualised level.”

Over and above that, as a personal encounter made clear, the past is not really past. Having been looking at harrowing material for 30 years, Pető believed she “could deal with anything”. But then she was contacted by two children of a woman who had been born from rape. They came to her office to tell their story, and Pető found herself “crying with them. When you are faced with the people whose pain is there, it’s very different [from reading about it in secondary sources]. I still feel moved by the pain and it gives me strength to tell the story.” It also made clear to her how “rapes during the Second World War are still with us, because the violence has continued in the lives of the women, their families and children”.

The CEU’s future in Hungary has been in doubt since Orbán’s government passed a law last year restricting the operation of overseas-registered institutions (the CEU is registered in New York state), widely seen as an attack on its liberal, democratic values. For the moment, Pető sees the university as “a safe space, intellectually and also existentially”. Although she was involved in a dispute under earlier management that led to “a four-year struggle in the Hungarian labour court to prove that I know what gender is”, she is now committed to “an institution which I think is important, which I helped to found, and [whose mission] I consider…crucial for the future of Europe and Hungary”.

In a paper written with Polish colleague Weronika Grzebalska and published in February in Women’s Studies International Forum, Pető compares the “illiberal democracy” that Orbán famously claims to be constructing with a polypore, “a parasitic fungus that feeds on a rotten tree while contributing to its decay”. She is encouraged that “gender studies was approved in public universities for the first time this year”, and that she has been appointed to the Hungarian accreditation body’s committee on the humanities. Yet she sees great danger in the way that the government is undermining the system by “withdrawing money from state-financed education and channelling it into the universities, research institutions and thinktanks [the politicians] have set up themselves”.

Since she spoke to Times Higher Education, the government has announced that research funding formerly distributed by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences will, from 2019, be allocated by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology instead.

In such a climate, it is little wonder that colleagues in less secure positions often resort to self-censorship, Pető says. But she feels that “what I’m doing is getting more and more important. I am writing more and more in Hungarian, trying to influence how people think, by asking questions and thinking together. I am doing lots of op-eds and journalism, which reach a total of 15,000-20,000 readers.” She has also launched a series of podcasts about the Second World War.

There remain many challenges for academics committed to feminist and progressive causes who have to operate within illiberal regimes. Fortunately, there are also a number of important precedents to draw on. In her May speech accepting the Madame de Staël prize, Pető made reference to a number of female writers and political figures who had inspired her. Yet she also spoke of “the kind of education, founded on rigorous intellectual work, on passion and volunteerism, that I myself had received in the seminars of the Budapest flying university during communism”, an underground institution that allowed dissidents to engage with topics not covered in state-controlled institutions. “This is the tradition represented by the CEU,” Pető adds.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: When the past is not history

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login