The idea of employability is full of paradoxes. The most striking is that, while universities and employers agree that it’s increasingly important for graduates, there’s little agreement on what it means.

The Technical University of Munich is the only institution outside the US, UK or Japan to make it into the top 10 in the new Global University Employability Survey, designed by French human resources company Emerging and published exclusively in Times Higher Education (see box below for details of the methodology). Wolfgang Herrmann, TUM’s president, credits this success to the deep relationships between the university and industry in Bavaria. The university’s academics also work for companies such as BMW, Siemens and Lindner, which gives students an immediate insight into the work environment.

“There is no other technical university that has such a rich economic environment and especially a technical economic environment [as] we do here in Munich,” says Herrmann.

A number of other institutions at the top of the ranking – including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the California Institute of Technology and Stanford University – are also well known for their industry connections and entrepreneurial environment.

Nonetheless, Brett Alpert, Stanford’s associate dean of career education (and director of its employer engagement programme, known as Career Ventures), puts less stress on specific relationships with companies and instead plays up the opportunities for students to have a broad range of experiences at university. “It is important for students entering today’s workplace to connect with many different people, from a range of professions, in order to discover potential areas of interest and opportunities in fields that they may not have initially considered,” he says.

“A broad-based curriculum is certainly beneficial in helping students develop the combination of leadership skills, critical thinking skills and technical expertise needed to successfully navigate workplace and societal challenges and opportunities – while enabling them to find success not only in their careers, but in life more generally.”

This view is echoed by Shelagh Green, director of the careers service at the University of Edinburgh and president of the Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services. “In many institutions, there is a sense that we want higher education to be transformative: the idea that the student can explore and experiment and be encouraged and supported to do that, so that they are inquisitive about themselves and the world around them, and as a consequence they become more self-aware and more aware of the [career] opportunities that might be open to them,” Green explains.

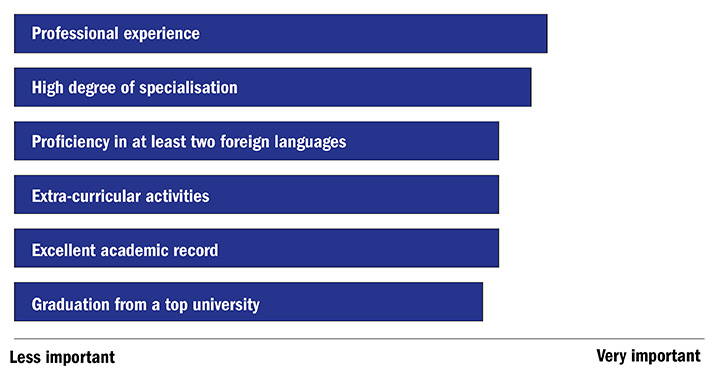

However, despite this holistic approach to employability advocated by some careers advisers, most employers are clear that “professional experience” and a “high degree of specialisation” are the best predictors of employability in graduates.

It is here that we encounter another paradox. Recruiters judge “graduation from a top university” as the least important of a number of predictors of a graduate’s employability. Yet the new employability ranking – derived from the votes of the very same recruiters – nonetheless puts the world’s most prestigious universities, such as Harvard, Cambridge, Yale and Oxford, near the very top.

The paradox is that while employers in principle recognise that a degree from a top university is not necessarily indicative that a graduate has the “essential skills” for a professional environment (and conversely that a graduate who might prove a perfect fit for a job role will not necessarily have studied at a prestigious institution), many recruiters feel compelled to defer to university reputation or rank in the first instance as a way to select from large numbers of applicants.

One explanation for this is increasing international mobility. In 2014, for instance, there were more than 5 million internationally mobile students around the world, up from just over 2 million in 2000. As employers receive more international applications, it becomes ever more important for ambitious students to graduate from a university that has a “global brand”.

Predictors of employability and the importance of employability skills

Which of the following skills and experiences are the most predictive of a graduate’s employability?

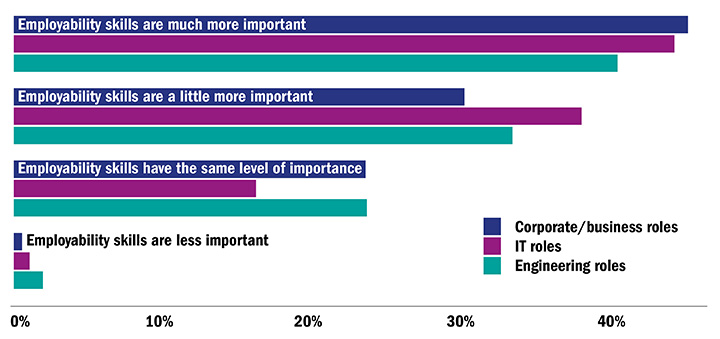

When you think about recently employed graduates, how do you rate the importance of employability skills against specific technical or academic knowledge and skills associated with their degree?

Source: Global University Employability Survey 2016 © Emerging

That is certainly the view of Laurent Dupasquier, associate director of Emerging. “Suddenly you have students who are really looking globally, they are looking for a specific brand. Their degree is going to be a brand: something they can use as a passport all their life, which will allow them to work anywhere in the world and for companies of any nationality,” Dupasquier says.

Edinburgh’s Green also knows of employers who select by university as “an easy way of managing the numbers” – although she also notes that some organisations “actually have a negative view of the elite universities” and make a point of not recruiting from them.

Ashley Hever, talent acquisition director at Enterprise Rent-A-Car, a company Green praises for having a particularly robust and fair recruitment process, says that recruiting from a wide range of universities and not just from an elite few is important for them as employers. “University qualification and reputation are somewhat important. However, we value a candidate’s life skills and experiences more highly, and we do recruit people with every kind of degree, from more than 800 universities worldwide,” Hever says.

Another crucial challenge is the highly dynamic nature of many industries, which means that university teachers and advisers, and indeed students themselves, cannot predict the technical knowledge that will support graduates throughout their careers.

For Kate Lander, global chief learning officer at Fitch Learning, this situation has left a generation of graduates overqualified academically but underprepared for a workplace where the right attitude and behaviour can often be more important than specific knowledge.

In financial services – the sector in which Fitch runs graduate training programmes for clients – the effect of both regulatory changes and technological advances has been a shift away from highly specialised technical employees towards professionals who can apply their knowledge appropriately in a changing environment.

Eden Woon, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology’s vice-president for institutional advancement, agrees that the ability to apply knowledge should be a priority for today’s graduates, but argues that there is still significant value in having specialised academic knowledge: “Students have to realise that while they will be majoring in a specific area, it is difficult to know what jobs will be available in 10 years. But everybody should major in a specific area because that really gives them the depth of knowledge in some field and it also gives [them] the challenge of diving deeply into a certain subject.

“But I think just as important as being knowledgeable about a specific subject is the ability to adapt, be innovative and to apply knowledge in different ways,” he says.

This delicate balance between academic specialisation and the ability to apply knowledge flexibly may go some way to explaining HKUST’s success in the Global University Employability Survey, where it is placed 13th (above, for example, Imperial College London, the National University of Singapore and the University of California, Berkeley).

However, says Woon, “we are very firm in the belief that the university is not a vocational training institute. So the purpose of the university is not just to prepare you for jobs. The purpose of the university is really to give students a skill so that they can go and find a job but, more importantly, it is really to prepare students for what happens after they get a job. In other words, whether they can adapt to the job and adapt to changes that the world requires of them. That is where innovation, creativity and attitude come in.”

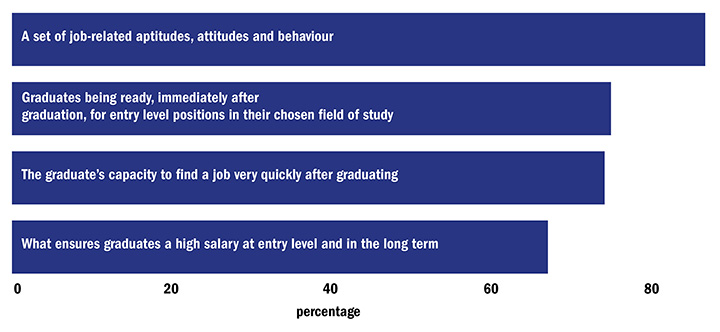

In the survey, just under 90 per cent of employers define employability as “a set of job-related aptitudes, attitudes and behaviours”, naming adaptability, teamwork and communication as some of these traits.

If attendance at a top university is not a good indication that graduates are adaptable, able to work effectively in a team and can apply knowledge in a variety of situations, how can employers determine that they actually possess these so-called soft skills?

Defining employability

Recruiters agree or strongly agree that employability means:

Source: Global University Employability Survey 2016 © Emerging

Lander explains that such traits are “much harder to assess initially”, so recruiters look for them only after a “first level of screening focused on what we would call objective facts – some will call it a box-ticking exercise – which will ask whether graduates have got the minimum requirements expected and will scan for qualifications”.

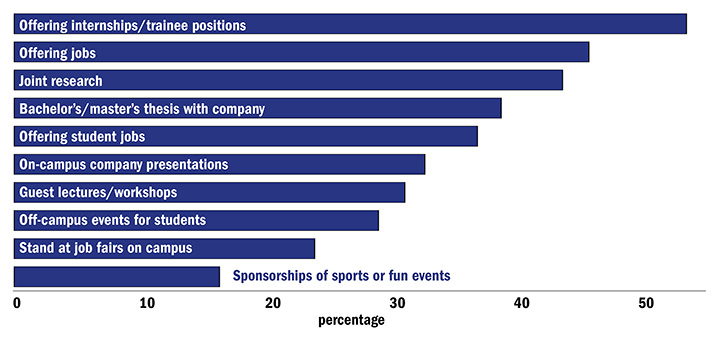

One obvious way for employers to judge behaviour and mindset, beyond academic credentials, is to use internships and work experience as a testing ground. Asked which type of cooperation between companies and universities will become more relevant in the future, more than half of employers named internships.

IE University in Madrid has been steadily climbing the employability ranking over the past few years. Amber Wigmore, executive director of careers services, believes that this is at least in part due to selecting employable students in the first place: “IEU’s admission process secures [more employable graduates]. In the IE Career Management Center, we work closely with our colleagues in admissions so that they are abreast of the top skills sought after by recruiters.”

Selecting for these skills might be seen as a reasonable approach for universities aiming for impressive employability figures, given that educators and careers advisers tend to find employability a very difficult subject to teach.

This also raises a broader issue. Should universities take responsibility for cultivating the skills required in professional environments, or should this be largely up to the students themselves or employers providing on-the-job training for graduates?

This question is particularly pressing in Canada, where there are worries about a relatively low level of skill in the adult workforce, despite high national performance in post-secondary education.

A 2014 education report by the Conference Board of Canada called “How Canada Performs” says: “It is noteworthy that some countries with lower levels of educational attainment than Canada are outperforming Canada on adult skills; Norway and Finland are two examples. This may, in part, be a function of the relatively high participation rate of adults in non-formal job-related education in these two countries.”

This prompted Daniel Munro, the principal research associate at the Conference Board of Canada, to write an article in the Financial Post imploring Canadian employers to step up their investment in skills training.

Munro diagnosed the underlying problem as “employers’ belief that they can shift the cost and responsibility for training on to the publicly funded post-secondary education [PSE] system”, and noted a “troubling correlation” between the 40 per cent decline in employer spending on training over two decades and increasing calls for higher education providers to “produce work-ready graduates”.

“When employers believe that they can externalise skills development to formal education systems, they feel less urgency to make training investments with their own limited resources,” Munro wrote. “Employers need to think differently about the role of the PSE system. PSE graduates have great knowledge and expertise to offer, as well as a capacity for future learning. But given that employers have unique skills needs, adopt new technologies and innovate, their success will depend on skills development well beyond their employees’ graduations.”

Nonetheless, Canadian universities are working hard to improve the employability of their graduates. McGill University ranks in the top 20 worldwide for employability, something that Darlene Hnatchuk, the director of its Career Planning Service, attributes to a range of different factors: the rigorous academic programmes, selective admissions, a highly international student body and staff, experiential learning opportunities, self-directed engagement in extracurricular activities and comprehensive student support services.

Yet what is fundamentally important, she says, is the time and space for students to reflect and learn from their experiences. “The challenge we see in careers services is that students are pressed for time as they balance their academic schedules and other work or volunteer experiences,” Hnatchuk explains.

Company/university links

What type of cooperation between companies and universities will become more relevant in future?

Source: Global University Employability Survey 2016 © Emerging

“It is hard for them to find time…for the intentional review, analysis of and learning from their experiences that can help provide clarity in decision-making, as well as enhance their skills in all areas. This is a key process when we speak about the value of lifelong learning and what it means to be a professional. It is also a key skill that we can help instil in our students as we prepare them for the ever-developing world of work.”

These themes of personal reflection and self-development are flagged up by university careers services around the world. Some initiatives aim to integrate employability skills into the recreational activities that students already engage in, rather than expecting students to seek out specific career development opportunities.

“You bring employability and self-reflection into other activities,” explains Edinburgh’s Green.

“We [at the Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services] do a lot of work with student sports societies, where students are encouraged to set themselves goals in their sporting environment and to reflect on those, to peer-assess each other, [not] on their capability [but] on their engagement with the process of development. Employability is not taught. It is about a range of experiences and I think, for universities, supporting student development and employability is a mutually beneficial part of the educational experience because better students are better employees.”

Some universities, particularly technical institutions, use more formal methods to enhance students’ practical skills and application of knowledge. At HKUST, for instance, lecturers use “flipped classrooms” where in-class work is focused on projects and case studies. In Switzerland, students at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, which ranks 35th in the world for employability, benefit from career-focused teaching throughout their time at university.

Pierre Vandergheynst, the vice-provost for education, says that they “put a lot of emphasis on key skills for the job market during education at EPFL. For instance, our curricula feature a large fraction of hands-on labs and projects that prepare students to solve real-world problems. EPFL has recently launched a school-wide initiative, the Discovery Learning Programme, which focuses on these skills via new pedagogy and new facilities.”

A key challenge for employability, according to Stanford’s Alpert, is ensuring that students engage with the career development process early enough.

“It is no longer effective for students to wait to visit a career coach on campus for the first time just before graduation in order to figure out how to write a résumé,” he says. “That type of activity really should take place early in the student’s academic journey, so that they can instead focus much of their professional development efforts on building connections, attending career-focused programmes and pursuing internships and other experiential learning opportunities.”

For Stanley Litow, IBM’s vice-president of corporate citizenship, even beginning career development on entry to university is not early enough. His team has developed a public-private partnership programme, piloted in New York City, which provides a direct pathway from high school to college to a job in the technology sector.

IBM’s P-TECH (Pathways in Technology Early College High School) programme integrates what Mr Litow calls “essential skills” for the workplace into a curriculum that starts in high school, using workplace learning, work experience and project-based learning. Within six years, students receive a high school diploma, a college degree and, in all likelihood, a job in the technology sector, either at IBM or another company.

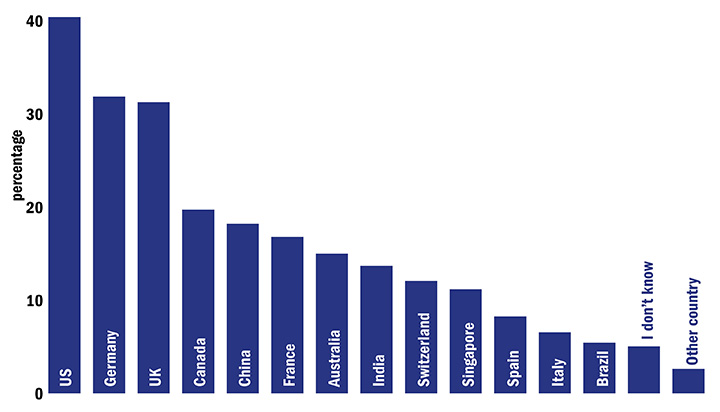

Countries producing the most employable graduates

Based on your own experience, which of these foreign countries produce the most employable graduates?

Source: Global University Employability Survey 2016 © Emerging

“While there are some differences, if you look at entry-level skill requirements across a variety of different industry areas, the commonality is that these essential skills are critically important. In IT, you might need coding, but you will also need writing, problem-solving, collaboration, presentation – all those critical skills – to be successful.”

Although most of the first students on the pilot P-TECH programme in New York are only now in their sixth and final year, 40 (out of a total cohort of 100) completed the course early and have graduated. About 10 are already employed at IBM.

Litow believes that this success – and an extremely low dropout rate – can be attributed to students learning in all their classes how academic knowledge will prove useful in the workplace. This creates more commitment, higher levels of engagement and a higher level of performance. The programme has now expanded across the US and to Australia and Morocco.

In March 2015, the UK government attempted to “shift the paradigm” in a rather different way, when it announced nine new industry-designed degree apprenticeships. These combine a full degree with professional training, with the cost covered by the employer and the government. The Skills Funding Agency estimates that between 1,500 and 2,000 students enrolled on these programmes in 2016 across 40 universities.

But Peter Horrocks, vice-chancellor of the Open University, where three degree apprenticeships are on offer, has noted a “slightly snobbish” attitude towards the programmes in the higher education sector.

Fitch Learning’s Lander also sees this as a key difference in approaches to employability between the UK and other parts of Europe. “If you look at the top banks in Switzerland and Germany, the senior players have often come down the apprenticeship route. It is very socially acceptable there, which means that even though they may come out with a degree – not straight from university, perhaps done while working – they are getting into the workplace and picking up workplace skills a lot sooner.

“Based on feedback we get from some UK employers, they are quite envious of this different approach.”

And there is a clear risk that the relative lack of integration of vocational elements into academic programmes could ultimately damage perceptions of UK graduates’ employability – and, indeed, of the quality of UK universities in general.

“Contrary to other rankings,” observes Emerging’s Dupasquier, “we are witnessing for the past two years that the medium-level English universities are going down in the employability ranking…and there is even one fewer UK university included than the year before.”

And while employability survey results could be seen as “highly subjective”, Dupasquier suspects that they can also offer an early indication of trends in the global higher education landscape; the Global University Employability Survey started including Chinese universities six years ago, for example, before they began rising in mainstream world rankings.

So perhaps the UK’s decline with respect to employability heralds the beginning of a wider trend.

The British paradox, according to Dupasquier, is that UK universities currently hang on at the highest levels of world university rankings, despite paying less attention than institutions elsewhere to the essential skills that are becoming increasingly important for graduates.

In time, he predicts, something will have to give.

Global University Employability Ranking 2016 results

| Rank | Institution | Country | Score |

| 1 | California Institute of Technology | United States | 927 |

| 2 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | United States | 887 |

| 3 | Harvard University | United States | 853 |

| 4 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 836 |

| 5 | Stanford University | United States | 805 |

| 6 | Yale University | United States | 800 |

| 7 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom | 773 |

| 8 | Technical University of Munich | Germany | 744 |

| 9 | Princeton University | United States | 713 |

| 10 | University of Tokyo | Japan | 677 |

| 11 | Boston University | United States | 648 |

| 12 | Columbia University | United States | 576 |

| 13 | Hong Kong University of Science and Technology | Hong Kong | 558 |

| 14 | University of Toronto | Canada | 541 |

| 15 | National University of Singapore | Singapore | 530 |

| 16 | Imperial College London | United Kingdom | 517 |

| 17 | Peking University | China | 508 |

| 18 | McGill University | Canada | 504 |

| 19 | University of California, Berkeley | United States | 487 |

| 20 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | Japan | 466 |

| 21 | HEC Paris | France | 465 |

| 22 | Australian National University | Australia | 438 |

| 23 | King’s College London | United Kingdom | 431 |

| 24 | University of Manchester | United Kingdom | 420 |

| 25 | IE University | Spain | 417 |

| 26 | EMLYON | France | 415 |

| 27 | ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | Switzerland | 403 |

| 28 | Duke University | United States | 382 |

| 29 | Johns Hopkins University | United States | 378 |

| 30 | Brigham Young University | United States | 372 |

| 31 | LMU Munich | Germany | 368 |

| 32 | University of Edinburgh | United Kingdom | 367 |

| 33 | École Normale Supérieure | France | 366 |

| 34 | Dartmouth College | United States | 348 |

| 35 | École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne | Switzerland | 339 |

| 36 | Mines ParisTech | France | 336 |

| 37 | Fudan University | China | 333 |

| 38 | Indian Institute of Science | India | 331 |

| 39 | New York University | United States | 329 |

| 40 | Brown University | United States | 328 |

| 41 | University of California, Los Angeles | United States | 319 |

| 42 | CentraleSupélec | France | 312 |

| 43 | École Polytechnique | France | 311 |

| 44 | University of Montreal/HEC | Canada | 308 |

| 45 | London School of Economics and Political Science | United Kingdom | 307 |

| 46 | University of British Columbia | Canada | 305 |

| 47 | University of Melbourne | Australia | 303 |

| 48 | University College London | United Kingdom | 301 |

| 49 | University of Sydney | Australia | 297 |

| 50 | Goethe University Frankfurt | Germany | 291 |

| 51 | University of Copenhagen | Denmark | 287 |

| 52 | Carnegie Mellon University | United States | 285 |

| 53 | Shanghai Jiao Tong University | China | 284 |

| 54 | Cornell University | United States | 283 |

| 55 | University of Chicago | United States | 282 |

| 56 | Heidelberg University | Germany | 279 |

| 57 | Monash University | Australia | 276 |

| 58 | Ghent University | Belgium | 273 |

| 59 | Tsinghua University | China | 272 |

| 60 | University of California, San Francisco | United States | 269 |

| 61 | Humboldt University of Berlin | Germany | 268 |

| 62 | Stockholm University | Sweden | 266 |

| 63 | KU Leuven | Belgium | 265 |

| 64 | University of New South Wales | Australia | 263 |

| 65 | Kyoto University | Japan | 262 |

| 66 | University of Navarra | Spain | 259 |

| =67 | Hebrew University of Jerusalem | Israel | 256 |

| =67 | Frankfurt School of Finance and Management | Germany | 256 |

| 69 | University of Zurich | Switzerland | 255 |

| 70 | University of Helsinki | Finland | 252 |

| 71 | University of São Paulo | Brazil | 247 |

| 72 | Delft University of Technology | Netherlands | 245 |

| 73 | National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (Taiwan Tech) | Taiwan | 244 |

| 74 | ESSEC Business School | France | 242 |

| 75 | McMaster University | Canada | 241 |

| 76 | Technical University of Denmark | Denmark | 237 |

| 77 | University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 235 |

| =78 | Lund University | Sweden | 231 |

| =78 | University Commerciale Luigi Bocconi | Italy | 231 |

| 80 | University of California, San Diego | United States | 230 |

| 81 | Karlsruhe Institute of Technology | Germany | 227 |

| 82 | Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) | South Korea | 226 |

| 83 | Michigan State University | United States | 224 |

| 84 | University of Bristol | United Kingdom | 221 |

| 85 | Chinese University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 220 |

| 86 | University Ramón Llull | Spain | 217 |

| 87 | Pierre and Marie Curie University | France | 216 |

| 88 | Eindhoven University of Technology | Netherlands | 214 |

| 89 | University of Southern California | United States | 212 |

| 90 | University of Birmingham | United Kingdom | 207 |

| 91 | KTH Royal Institute of Technology | Sweden | 205 |

| 92 | University of Göttingen | Germany | 202 |

| 93 | University of Nottingham | United Kingdom | 200 |

| 94 | Georgetown University | United States | 198 |

| 95 | Erasmus University Rotterdam | Netherlands | 193 |

| 96 | Technical University of Berlin | Germany | 189 |

| 97 | Sciences Po | France | 186 |

| 98 | University of Pennsylvania | United States | 182 |

| 99 | University of Lausanne | Switzerland | 181 |

| 100 | Northwestern University | United States | 180 |

| 101 | Nanyang Technological University | Singapore | 179 |

| 102 | Rice University | United States | 178 |

| =103 | University of Texas at Austin | United States | 177 |

| =103 | University of Washington | United States | 177 |

| 105 | University of Bern | Switzerland | 176 |

| 106 | Polytechnic University of Milan | Italy | 175 |

| 107 | Seoul National University | South Korea | 174 |

| 108 | Leiden University | Netherlands | 173 |

| 109 | Ohio State University | United States | 172 |

| 110 | Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education | Mexico | 171 |

| 111 | Zhejiang University | China | 170 |

| 112 | University of Groningen | Netherlands | 169 |

| 113 | Paris-Sud University | France | 168 |

| 114 | Texas A&M University | United States | 166 |

| 115 | Free University of Berlin | Germany | 165 |

| 116 | Karolinska Institute | Sweden | 163 |

| 117 | Purdue University | United States | 162 |

| 118 | Osaka University | Japan | 160 |

| =119 | Georgia Institute of Technology | United States | 159 |

| =119 | Nanjing University | China | 159 |

| 121 | Pohang University of Science and Technology | South Korea | 158 |

| =122 | Technion Israel Institute of Technology | Israel | 157 |

| =122 | University of Oslo | Norway | 157 |

| 124 | University of Alberta | Canada | 156 |

| =125 | University of Basel | Switzerland | 154 |

| =125 | Lomonosov Moscow State University | Russia | 154 |

| =127 | National Taiwan University | Taiwan | 153 |

| =127 | University of Science and Technology of China | China | 153 |

| 129 | Keio University | Japan | 152 |

| =130 | University of Michigan | United States | 151 |

| =130 | RWTH Aachen University | Germany | 151 |

| 132 | EDHEC | France | 150 |

| 133 | University of Geneva | Switzerland | 149 |

| 134 | Trinity College Dublin | Republic of Ireland | 148 |

| 135 | Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey | United States | 147 |

| 136 | University of Iceland | Iceland | 146 |

| 137 | Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa | Italy | 144 |

| 138 | City University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 141 |

| 139 | Tel Aviv University | Israel | 139 |

| 140 | University of Auckland | New Zealand | 137 |

| 141 | National Tsing Hua University | Taiwan | 134 |

| 142 | University of Florida | United States | 133 |

| 143 | University of Wisconsin-Madison | United States | 132 |

| 144 | University of Vienna | Austria | 130 |

| 145 | Saint Petersburg State University | Russia | 125 |

| 146 | University of Buenos Aires | Argentina | 122 |

| 147 | American-University of Dubai | UAE | 110 |

| 148 | University of Malaya (UM) | Malaysia | 109 |

| 149 | King Abdulaziz University | Saudi Arabia | 104 |

| 150 | National Autonomous University of Mexico | Mexico | 102 |

Global University Employability Ranking 2016 © Emerging

Global University Employability Ranking 2016 methodology

To produce the Global University Employability Ranking, an online survey was completed by two panels of participants between April and July 2016.

Both panels included respondents from 20 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the UK and the US.

The first panel consisted of recruiters at a management level who had experience of hiring or working with graduates. Each person was given a list of local universities (with the option to add more) and had up to 15 votes to cast for the “universities in [their] country [that] produce the best graduates in terms of employability”. The sample size of recruiters from each country was determined by the country’s number of university students, GDP and number of institutions.

Participants with experience recruiting internationally were also asked to select from a global list of universities that they considered “the best in the world when it comes to graduate employability”.

The second panel consisted of 3,450 managing directors of international companies. Participants could cast a maximum of 10 votes on both the local and global lists of universities that had been produced by the first panel. They could also add universities from a database.

Votes were then aggregated into scores for each university to produce the ranking.

Most participants had at least 10 years’ experience in the workplace and worked at a firm with more than 500 employees. More than 30 per cent had experience recruiting in the business sector, just under 30 per cent had experience in the IT sector, and almost 20 per cent worked in the engineering industry. More than half recruited internationally.

The survey was designed by the French human resources consultancy Emerging, and has been conducted for the past six years by employment research institute Trendence. It has been published exclusively by Times Higher Education since 2015.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Fit for work

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login