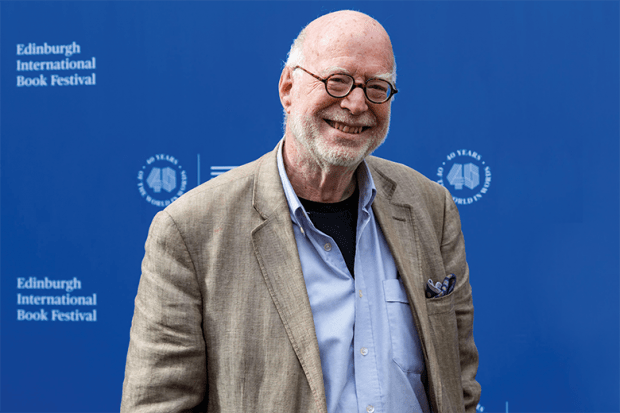

In 2018, Richard Sennett confirmed his reputation as one of the world’s leading thinkers on urban life by completing a trilogy of books on a vast and fascinating theme: “the skills people need to sustain everyday life”.

There were reasons, however, to fear that Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City – the sequel to The Craftsman and Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation – might be his swansong.

He had already, he wrote, had “an exploratory visit [from the Grim Reaper] in the guise of a stroke”, which led him to concentrate on “what really mattered” but also proved a strange sort of research tool. It helped him “understand buildings and spatial relations differently from the way I had before. I now had to make an effort to be in complex spaces, faced with the problem of staying upright and walking straight.”

Furthermore, needing to take regular exercise, he began to explore Kantstrasse in Berlin. When vertigo forced him to steady himself against shopfronts or walls, the lack of reaction from passers-by, beyond brief glances in his direction, offered vivid, first-hand evidence of how people in cities “don’t get involved” and “close off emotionally”.

All this must have sounded ominous for the many fans of Sennett’s work. But he is now back with the first volume of another ambitious trilogy, The Performer: Art, Life, Politics (Allen Lane). He hopes to follow it up with two further volumes, on narrating and picturing, so as to cover the full range of human “expressive DNA”. And, this time, the subject is one with which he is already intimately acquainted.

Now an apparently vigorous 81-year-old, Sennett is professor of sociology emeritus at the London School of Economics, having spent most of his career there and at New York University, although he notes that he has also “just become attached to Pembroke College in Cambridge, as a kind of hanger-on, because I know lots of people there”.

Yet he came relatively late and unexpectedly to academia. Sennett started off as a performing musician and, he recalls, “expected to spend my life as the last cello in a good orchestra”. When a hand injury and botched surgery put a stop to that, it was the political theorist Hannah Arendt who gave him “the self-confidence to go on in academia. She said, ‘You know nothing, but so what? You‘ve got a brain and can use it. So come and sit in on my lectures. If I can give you any advice, I will.’ That was wonderful.”

Two equally celebrated thinkers, neither of them “standard-issue academics”, later proved to be crucial intellectual interlocutors for Sennett, namely the French historian Michel Foucault and the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas. They would meet up regularly for animated discussions on topics such as “cosmopolitanism”, where levels of agreement or disagreement “depended very much on the time of day and the amount of alcohol we had to drink”.

Such interactions, for Sennett, are at the heart of a productive intellectual life: “Every intellectual needs a Viennese cafe. You don’t need a classroom or a seminar. You need a cafe where you can have one cognac too many and really lay it out and have somebody come back at you.”

Looking back, Sennett is well aware of how lucky he has been. In the 1970s and early 1980s, he reminds us, “there was a labour shortage of academics, which gave us a little more wiggle room in terms of flexibility. I had a wonderful freedom in my thirties and forties. I could write what I wanted.”

Alongside his research and teaching, Sennett has been involved in a number of small-scale planning projects, mostly for poor communities, in Beirut as well as Chicago and New York, and provided consultancy services to a number of UN agencies concerned with urbanism. Although his writing has always focused on the (very broad) themes of cities and labour, he has happily leapt over disciplinary boundaries and addressed his books far beyond a specialist academic audience. He imagines his ideal reader – rather strangely and specifically – as a female biologist: “Since I’m neither of those things, I have to ask myself two questions about what I am writing: would it interest her? And would it tell her anything that is not intuitively obvious? You want to assume your reader is someone like yourself [in terms of curiosity and intelligence], but has different experience. That seems to me to produce writing which will have some spine to it.”

Although full of wide-ranging learning, Sennett’s books are also notable for their personal touches. Together opens in a school playground in London, where a friend of Sennett’s grandson has commandeered the public-address system to blast out Lily Allen’s song Fuck You: “Fuck you, fuck you, very much”. Building and Dwelling describes his own youthful experience of living in New York’s West Village “above Dirty Dick’s Foc’sle Bar, an establishment…which catered for stevedores during the day and transvestites at night”.

It is another striking feature of Sennett’s books that he is very interested in areas of intuitive, non-verbal practical expertise familiar to performers but neglected by most academics. (The Craftsman, for example, examines the “link between hand and head among...musicians, cooks, and glassblowers”.) And he always aims, he says, to offer open-ended “discussions with the reader” rather than easy answers to complex questions.

All these features of his work have gained Sennett a huge cult following. “To call this captivating writer an academic sociologist,” a reviewer in The Independent once wrote, “makes as much, or as little, sense as labelling Mozart a court musician.”

As someone who became an academic as a second choice, Sennett has to some extent “always felt like a fish out of water in academia”, views it with a somewhat sceptical eye and deplores many recent developments. Reflecting on “the relation between intellectual life and academic life”, he has come to the conclusion that “They’re really diverging, particularly in the UK...The bureaucratic world has not made [a younger generation of academics] intellectuals any more.”

Asked about his obvious commitment to interdisciplinarity, Sennett responds: “I never understood what that word means! If you have a subject, you want to know everything about it, all sides of it.” In studying the political life of cities, for example, “if you don’t know about how concrete and glass are organised in urban space, you lose something about the environment in which people are practising politics.”

Furthermore, Sennett finds unhelpful “this notion of ‘I bring one specialised body of knowledge to something, somebody else brings another and somehow they intersect’”. Part of the reason why he decided to work at the LSE, where he helped to found the LSE Cities research centre, was that “you could start with a subject such as inequality and then figure out all the dimensions you needed to know about, rather than just following one approach”. In his ideal academy, departments would be organised around themes such as cities, truth and pleasure. That would work better, in his view, than “the bureaucratic parcelling out of the humanities and social sciences” into traditional disciplines, such as anthropology and sociology.

More broadly, Sennett would like to “organise higher education to be meaningful for people throughout their lives”. To do so, he envisages “the equivalent of gap years, so people would go out and work for five or six years and then start university at 25 or even 30. When I’ve had mature students, they’re always much more satisfying to work with.”

Most school-leavers don’t have a great deal of life experience, Sennett goes on, so “they have to rely on suppositional experience – what something should be like. And suppositional experience is exactly what adulthood should break down. It’s very easy to theorise about something when you don’t have experience to back it up. It becomes slick and all about defending a point of view.”

His ideal university, Sennett concludes, “would look much more like night school than an Oxbridge college”.

At the start of The Performer, Sennett boldly announces that he “wanted to think things out” for himself and hasn’t tried to “slot this book into the burgeoning academic field of ‘performance studies’”.

The book ranges from ancient Greece to modern Japan by way of Renaissance Venice, not to mention Louis XIV projecting his charisma by dancing in front of the French court. It also draws on direct experience, such as attending a gung-ho war film with a wounded veteran and a poignant performance of Shakespeare’s As You Like It on an Aids ward in the early 1980s, when the actors used flesh-coloured cream to “disguise the reddish-brown lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma on necks, faces and hands”.

So why does Sennett want to distance himself from the kinds of analysis one finds in performance studies?

His book returns to his time as a cellist and as “a sound artist”, who spent three months “splicing and gluing together the tapes” for experimental dance groups. He is very intrigued, he tells Times Higher Education, by the technical challenges of “how to use one’s technique in a way which is expressive” and much less by questions of representation and historical context.

“I’m not very interested in the identities of performers,” he explains, “whether they’re black or gay or anything like that. If you’re a black musician, what you’re struggling with is the same thing that every other musician is, not how to be black but how to perform well. It’s the art part of performing which interests me.”

Another central concern is the continuity between such artistic performance and malign forms of political manipulation. The book includes a disturbing account of a gathering of climate change sceptics Sennett witnessed at the Trump International Hotel. Though he disagreed with their views, he remembers now, “the kids were perfectly reasonable to chat to” over lunch, before they went off to hear a number of inflammatory speakers “performing a kind of climate denial – and performing it well. Then the theatrics catch them up and they lose consciousness of the fact that things are more complex. The moment the performance ends, a more judgmental, calm consciousness returns. It’s a collective surrender through theatre. And something like that may have happened with Brexit.”

As this may suggest, Sennett was partly spurred to write his new book by the rise of political performers who “can overwhelm the judgment of other people. Boris Johnson is a great example. So is Donald Trump...They know how to seduce, and, certainly, we were seduced by Boris Johnson. It was such a low point in what you might call the collective intelligence of the British people. He dumbed them down totally.”

In pointing to the “emotionally compelling...power of manipulative, malign performances”, The Performer also makes the sobering suggestion that the standard “liberal, enlightened remedy for changing people’s attitudes” – more information, more education – may not be enough to combat them.

Sennett has forged a hugely impressive career, of a kind that is hard to imagine today. Among many other topics, his books force us to think again about what higher education could and should be for.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login