With a near-record 113,000 postgraduate research students based in the UK, including 46,350 foreign PhD candidates, Britain’s doctoral education landscape would seem to be thriving. Buoyed by an extra £109 million from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) to support PhD and mid-career researchers in 2023-24, and Horizon Europe membership secured, there might appear little cause for concern.

But there are signs that things are not as rosy in UK doctoral education as some imagine. In November, the Student Loans Company noted the “first potential yet small decline in the take-up of postgraduate doctoral student loans”, with sums borrowed in 2022-23 down by 12.3 per cent.

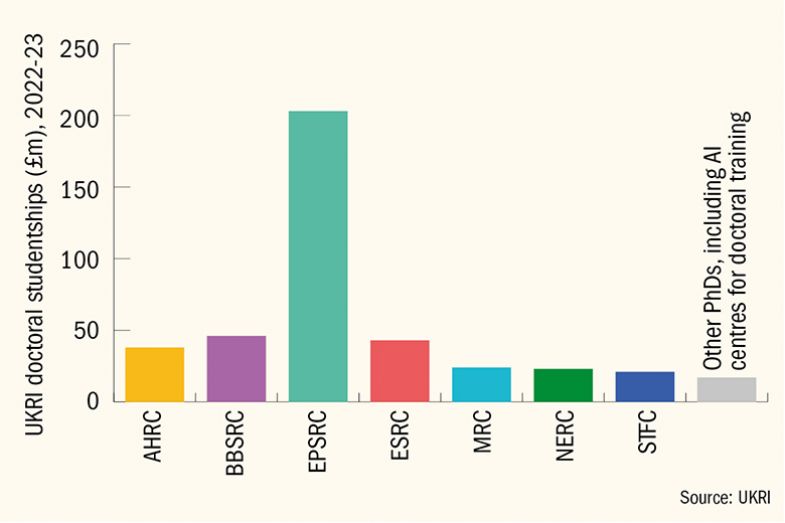

There are also indications that funded PhD studentships will not be as plentiful over the next few years. The biggest single funder of PhDs – the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), which sponsored nearly half of the 4,900 UKRI-backed doctoral students who began their studies in 2022-23 – announced last year that the number of its Centres for Doctoral Training (CDT) would fall from 75 to “about 40” from 2024, leading to about 1,750 fewer funded places over the next five years. In addition, the Arts and Humanities Research Council is reducing its PhD studentships by nearly a third, from 425 to 300 per year by the end of the decade, and the Wellcome Trust is severely reducing its support for PhD students under its new strategy to focus on longer grants for early- and mid-career scientists.

Things could get a lot worse in the next few years, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies warning that tax cuts announced in chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement would lead to budget reductions of about 3.4 per cent a year in “unprotected departments”, of which one might be the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

“It’s going to be tough going with an election and a spending review, whichever party wins,” predicted Rory Duncan, UKRI’s former director of talent and skills, who is now pro vice-chancellor (research and innovation) at Sheffield Hallam University.

If universities were forced to tighten research spending, support for PhD students could be an early casualty because doctoral researchers – while sometimes seen as a source of cheap labour – are big loss-makers for institutions, explained Professor Duncan. “If you look at Trac [Transparent Approach to Costing] data, the cost recovery for doctoral students is very low – the lowest for any type of research activity,” he said, pointing to data that showed UK universities incurred losses of £1.4 billion educating PhD students in 2021-22, claiming back just 46.6 per cent of the cost of training researchers.

In the money: PhD funding

Thanks to UK universities’ success in attracting higher paying international students, the sector has been able to cover such losses – which amount to £5 billion a year for research overall – but that balancing act is “becoming much more challenging due to government rhetoric” over foreign students, continued Professor Duncan. “There is huge pressure on the research sector and it’s becoming harder and harder to do research – which includes supporting PhD students,” he said.

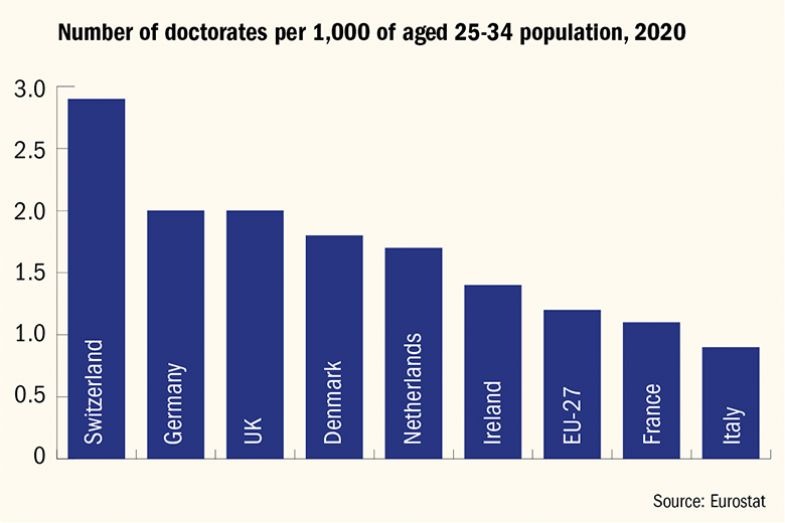

That will be bad news for the UK’s “science superpower” ambitions as the country’s innovation model had leaned heavily on having high PhD numbers, continued Professor Duncan. “For many years the UK has been a leader for investing in PhD training – it’s always been a top-three nation, alongside Germany and the US, for PhDs. Others, like Japan, have taken different routes and changed their support to focus on mid-career scientists, which has a very detrimental impact on research quality,” he added.

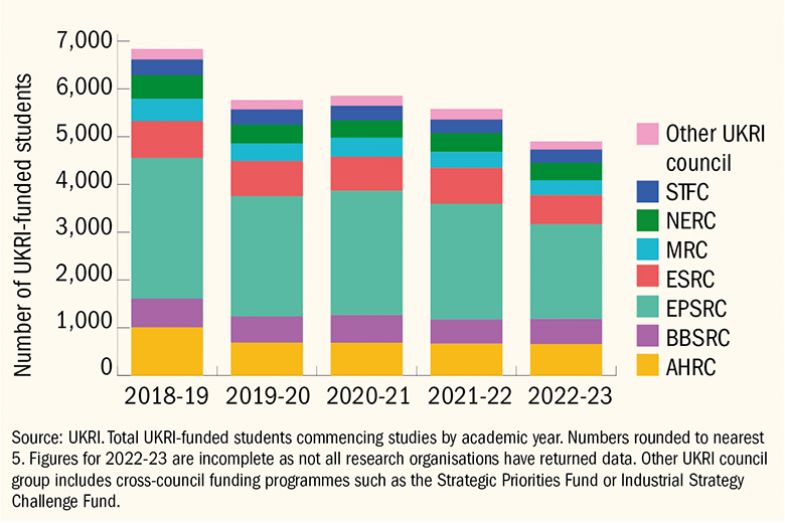

But the level of the UK’s investment in PhD training seems to be waning – at least, if judged on the numbers of doctoral students trained in recent years. A recent Freedom of Information request by Times Higher Education found the overall numbers of doctoral students starting UKRI-funded training fell from 6,835 in 2018-19 to 5,580 in 2021-22 – an 18 per cent drop – with reported figures for 2022-23 lower still at 4,900, though UKRI said this tally could increase as universities continued to submit data for that year. The decline in UK student numbers was even sharper, falling from 4,815 new candidates in 2018-19 to 3,420 in 2021-22 – down by 29 per cent – and to 2,840 in 2022-23.

Wrong numbers: falling PhD figures

For Douglas Kell, a former executive chair of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, such reductions are distinctly at odds with the government’s desire to attract an extra 150,000 researchers into the workforce by 2030.

“Cutting funded PhD numbers under any circumstances, especially in a knowledge economy, is simply short-termist and absolute madness,” said Professor Kell, now based at the University of Liverpool, who observed that these “further cuts extend those that have already been going under this administration for more than a decade. We need massive increases in those who are technically and intellectually qualified, not cuts.”

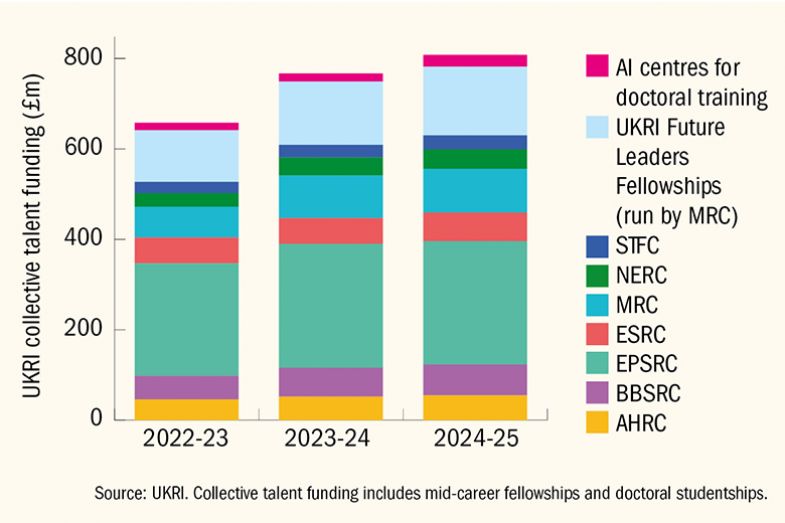

However, UKRI’s collective talent funding – which supports both PhD studentships and mid-career fellowships – is due to increase by only 5 per cent in 2024-25, so funded places could “go down in the absence of additional investment”, warned Professor Duncan, citing the continued need to increase tax-free doctoral stipends in line with inflation.

Group interests: talent funding

The hefty increases to UKRI’s stipend – £18,622 in 2023-24, up by 20 per cent from 2021-22 – might still not be enough to fix a bigger issue facing doctoral education, according to Robert Insall, professor of computational cell biology at UCL. “A lower proportion of the most brilliant students are doing PhDs – those who are really ambitious and who might become future leaders in their field,” said Professor Insall. “Even if you increased the stipend by 10 per cent again, it might not be enough to make it acceptable. Its level was acceptable a few years ago but now it just isn’t.”

The gloom hanging over UK higher education and research might explain why “the attractiveness of a PhD has gone downhill” for high-flyers who might have previously considered a research career in academia, continued Professor Insall. “The government is not selling British academia and the media is painting it as a very troubled place, so students and potential PhDs see that,” he said.

For its part, UKRI seems alert to the challenge of keeping the PhD attractive, with plans for a new “core offer” around professional and career development set to be unveiled this year. According to chief executive Dame Ottoline Leyser, this would “provide consistent talent offers that are still responsive to the needs of individuals and disciplines” and “strengthen the crucial link between career diversity and excellent research and innovation, better enabling people to follow their ideas across disciplines and sectors”.

Concerns over the direction of travel remain, but the fact that the UK is still a key destination for postgraduate students, behind only the US, suggests its doctoral model is far from broken, said Giulio Marini, visiting professor of education at the University of Hong Kong, whose research has focused on how PhD graduates fare in global job markets. “The UK is highly attractive, and it seems it will remain so – Brexit was not helpful, but now that the UK is back into European funding schemes I would not worry too much,” he said.

However, its international popularity among foreign PhD students might serve UK universities but not the UK economy in the long run if restrictive immigration rules push them to leave after a few years, warned Dr Marini. “If PhDs do not continue to live in the UK, their economic contribution will be limited. In that situation, UK universities are really ‘making brains for other countries’, which is not good policy.”

Is there a doctor in the house?: PhD population

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login