The number of PhD students winning UK research council funding has fallen sharply in recent years, according to data that shows that domestic candidates are increasingly being squeezed out by international applicants.

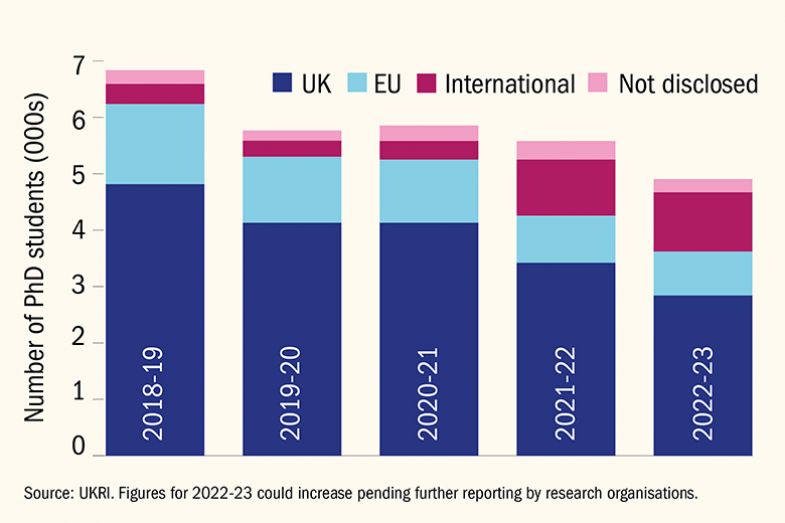

Figures obtained by Times Higher Education show that UK Research and Innovation funding councils supported 5,580 doctoral starters in 2021-22, down 18.4 per cent on the 2018-19 total of 6,835. Figures for 2022-23 indicate an even sharper drop – down 28.3 per cent to 4,900, although UKRI said that this tally could increase as research organisations submit further details of new recruits.

The declines are particularly steep among British students. In 2018-19, UKRI supported 4,815 doctoral candidates from the UK alone, but by 2021-22 this had fallen by 29 per cent, to 3,420. The 2022-23 figure provided, 2,840, indicates a 41 per cent drop over five years.

Total UKRI-funded doctoral candidates commencing studies by academic year

The shifts coincide with UKRI’s decision to extend full PhD studentships to international students, which came into effect in 2021-22. The previous year, when they were eligible for fees-only awards, 345 students from outside the UK and the European Union started publicly funded PhDs in the UK. This then tripled to 1,020 in 2021-22 and, according to the 2022-23 data, 1,055.

While international students made up 6 per cent of UKRI-backed starters prior to the policy change, they now represent 22 per cent. Meanwhile, the UK proportion has fallen from 70 per cent in 2018-19 to 58 per cent in the latest data. The share of EU students has fallen also, from 21 per cent – 1,420 students – in 2018-19, to 16 per cent – 780 students – in 2022-23.

UKRI, which funds about one in five of the estimated 105,000 doctoral students in the UK, caps the proportion of international PhD students it funds at 30 per cent.

Daniel Rathbone, deputy executive director of the Campaign for Science and Engineering, said the decline in UKRI-backed PhD starters was troubling given the UK’s ambitions to find an additional 150,000 researchers and technicians by 2030, as outlined in its 2021 R&D People and Culture Strategy.

“To meet the government’s ambitions to be more research-intensive, the UK will need a substantial increase in researchers. It is worrying, therefore, to see the number of students starting UKRI-funded PhDs has fallen in recent years,” said Dr Rathbone.

“We would urge the government to make sure that UKRI has the necessary funding for PhD studentships, and for students to be well supported during their studies.”

The data, which was provided following a Freedom of Information request, shows that the declines in the number of UK PhD students supported were particularly pronounced at certain research councils. At the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the UK total was down to 1,445 in 2021-22, and 1,150 in 2022-23, compared with the 2018-19 figure of 1,980. At the Medical Research Council, the number of UK students supported has almost halved from 325 in 2018-19 to 195 in 2021-22 and 180 last year.

The data is also likely to raise further concerns over PhD funding provided by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, which announced in September that it would cut the number of doctoral students it supports by a quarter, to 300 a year. In 2018-19, it supported 1,010, of which 660 were from the UK, while the 2022-23 data puts the overall total at 660, with 355 of these from the UK.

“Anyone who cares about the arts and humanities should be concerned about these figures,” said Andrew McRae, dean of postgraduate research at the University of Exeter.

“With only 355 places to UK arts and humanities applicants in 2022, and with more cuts to come, I wonder how long I can reasonably look talented undergraduates in the eye and encourage them to take on the additional debt repayments that will come with a master’s loan, in the hope of getting a foothold on the academic ladder.”

Professor McRae said that while he was “broadly supportive of an internationalised field of [postgraduate researchers] being supported by UKRI”, opportunities for domestic students were now “seriously constrained” and further reflection may be needed.

“We risk seeing some research areas becoming non-viable,” Professor McRae added. “I’m not seeing any coordinated thinking about the future academic staffing and research base for UK universities.”

In its recent publication, A New Deal for Postgraduate Research, UKRI said that it would keep its support for international students “under review”. In a statement, it said that 2018-19 was a “particularly high year for doctoral enrolments in the UK”.

“UKRI continues to work with the sector to monitor the rate of doctoral studentships and consider how best to invest public money that ensures students are appropriately supported and we can meet the government’s ambitions,” UKRI said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login