Doctor of physics and poetry

From its first title card in November 1963, the world’s longest-running science fiction series, Dr Who, has long played with the title character’s ambiguous relationship to academia.

Doctor Who is the obvious question asked by many characters, but viewers are also left to ponder another more intriguing headscratcher: Doctor of what? There is no categoric answer, but the different responses provided over the years are both playful and intriguing.

The programme’s early brief was for entertainment that educated through the Doctor’s scientific and historical adventures with companions Susan (his teenage granddaughter) and her two schoolteachers. The historical stories, particularly, often contained no science-fictional element but the Tardis itself. However, their depiction of academia was based on little experience; of Doctor Who’s 10 earliest producers and script editors, none held university degrees.

That may explain why the Doctor’s academic standing was often ambivalent. “I’m not a doctor of medicine,” the first Doctor (William Hartnell) tells schoolteacher Ian, irritably: in his pinstriped trousers, he is Edwardian, gentlemanly, eccentric. His successor, the trickster second Doctor (Patrick Troughton), was more ambivalent again, refusing to directly answer whether his doctorate is in law or philosophy: “Which law? Whose philosophies, eh?”

With the third Doctor (Jon Pertwee) came change: colour transmission, an expanding Time Lord mythology, and exile to Earth. Overseeing these was Terrance Dicks, the first Doctor Who script editor to be university educated (Downing College, Cambridge).

Under Dicks, the Doctor’s relationship with academia crystallised, including a degree in cosmic science, albeit of a lower class than his rival from his native Gallifrey, the Master: “I was a late bloomer,” he says, defensively. But he remains arrogant, telling companion Liz Shaw (a PhD and Cambridge research scientist) he is a doctor of “practically everything, my dear”. Notably, Liz is always “Miss Shaw”, never “Dr Shaw”. There is only one Doctor.

Dicks’ tenure is, in fact, littered with academics, most of whom are referred to as “Doctor” or “Professor”. This period is also the only time the Doctor’s rival, the Master, impersonates an academic. Disguised as Professor Thascalos, he is exposed by his lack of academic networks: “How is it,” asks the infiltrated institute’s director, “that you publish nothing?” The Doctor stands on firmer academic ground, earlier telling a sceptic he certainly has published on time travel – just not on Earth.

Later script editors created Gallifrey’s Time Lord Academy (from which the Doctor graduated, “scraping through with 51 per cent at the second attempt”) and encoded Time Lords as ivory-towered academics and “dusty senators”. Academically inclined companions often struggled to distinguish education from experience, such as Adric, who died through intellectual over-confidence. This process culminates, in the mid-1980s, in companion Ace, a working-class teenager expelled from high school. What educational opportunities are there for Ace in Thatcherite Britain, aside from this wanderer outside the academy, whom she calls “Professor”?

Since the arrival of David Tennant’s 10th Doctor in 2005, playful ambivalence around academia has been embraced, driven by tertiary-educated showrunners Russell T. Davies (Worcester College, Oxford), Steven Moffat (University of Glasgow) and Chris Chibnall (St Mary’s College, Twickenham). The 10th Doctor is intellectually confident and openly sarcastic: “Oh, 57 academics just punched the air,” he says, deflecting William Shakespeare’s heavy-handed flirting, and later tells an archaeologist that, as a time traveller, “I point and laugh at archaeologists.”

Challenged to confirm he is a real doctor (“You don’t just have a degree in cheesemaking or something?”), the 11th Doctor (Matt Smith) is briefly indignant: “No! Well, yes, both actually.” The first female regeneration, the 13th Doctor (Jodie Whittaker), claims to be a doctor of Lego, candyfloss and hope, but also medicine and philosophy.

The new incarnations have even shown the Doctor thoroughly embracing academia. Peter Capaldi’s 12th Doctor is the first to occupy an academic position, lecturing for 70 years at St Luke’s University on physics and poetry interchangeably (“Poetry, physics, same thing”), from a richly appointed office on the desk of which stands a photograph of granddaughter Susan. Here, he plucks new companion Bill Potts from the canteen. Like Ace in the 1980s, Bill is intelligent, curious – and debarred from traditional education.

Earlier in the 12th Doctor’s run, companion Clara overhears a dismissive voice from the Doctor’s childhood: “Well, he’s not going to the Academy, is he, that boy?”

But he is. And his ambivalent relationship to it draws in others, including the audience. Through all regenerations, the Doctor is still a doctor – but the question of Doctor Who remains.

Catriona Mills is the content manager of AustLit, a bio-bibliographical database recording the history of Australian literary and storytelling cultures, and is based at The University of Queensland.

A law unto herself

In the final episode of US television series How to Get Away with Murder (2014-20), criminal law professor Annalise Keating tells us who she is: “I’m ambitious, black, bisexual, angry, sad, strong, sensitive, scared, fierce, talented, exhausted.”

Played by the breathtakingly brilliant Viola Davis over six action-packed seasons, Professor Keating is an antidote to the kind of white, male, commitment-free academic depicted in so many campus fictions and embodied by her husband – a cocky, privileged, philandering white male psychology professor who is rather symbolically killed off in episode one.

The show’s promotional materials emphasise that Keating is “everything you hope your criminal law professor will be – brilliant, passionate, creative and charismatic. She’s also everything you don’t expect – sexy, glamorous, unpredictable and dangerous.” She’s the “real deal” – successful in her legal practice and her teaching, challenging critiques underlying the well-known aphorism: “those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.” She instructs with live briefs, asking students to come up with strategies to defend her firm’s clients against accusations of murder and other high-profile crimes. Her unconventional instruction draws students to her always in-demand class, referred to by the university as Introduction to Criminal Law but by Keating, much to the delight of hundreds of rapt learners, as How to Get Away with Murder.

Her employer, Middleton University, is a prestigious Philadelphia institution founded in 1802. Its age and architecture associate it in audiences’ imaginations with the Ivy League, and, when touring the campus, students are told that its graduates “make up a Who’s Who of our nation’s most prominent legal minds”. Keating also inculcates a highly competitive environment for students, singling out five of them (the Keating Five) to intern in her firm. Yet this competition is revealed to be less about merit and more about nepotism, with selection based not on hard work or skill but parentage. Here, the series reflects broader debates about the privilege at play in universities.

Despite her popularity with students, it’s never smooth sailing for Keating with the university leadership. Early on, audiences discover she was only hired as an assistant professor and has not achieved tenure. She later gets it, but threats to her employment continue to overshadow her career. At one stage, a university board member sends an incriminating video that gets her law licence revoked, and she is told that as practising law is in her contract, her tenure may be nullified.

Unlike in many campus fictions, in which a research-only role is positioned as the pinnacle of academic desire, How to Get Away with Murder positions a research role as failure – it’s what Keating is threatened with when the institution wants rid of her. And institutional data is used against her when it’s revealed that the Keating Five are achieving low grades despite their success as interns – being a student and working at the same time, it turns out, is not a very effective combination. All this reflects the drama’s place in what my colleague, Kay Calver, and I have argued is a shift toward “darker” and more disturbing representations of university life on screen.

Davis, who became the first black actress to win the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress for her performance, has revealed that she was central in the decision to include a much-praised scene where her character removes her wig and make-up, revealing the lengths that women, especially black women, must go to in order to present themselves in a way that is deemed socially desirable. The series also deals with many other sensitive and often under-represented themes. Keating’s experiences of pregnancy and baby loss, alcoholism and of childhood sexual abuse are woven throughout, and one of the most memorable and moving scenes for me is when, distraught and exhausted, she expresses breast milk after her baby son’s death.

Keating is a totally three-dimensional, complex and challenging character, revealing not just many of the unspoken lived realities of female university professors but of women more broadly. Smart, powerful, sexy, unfairly treated, vulnerable and so much more, she is number one in my fictional academic hall of fame.

Bethan Michael-Fox is a staff tutor in the School of English and Creative Writing at the Open University and managing editor for the academic journal Mortality. Her research focuses on popular cultural representations.

Space oddities

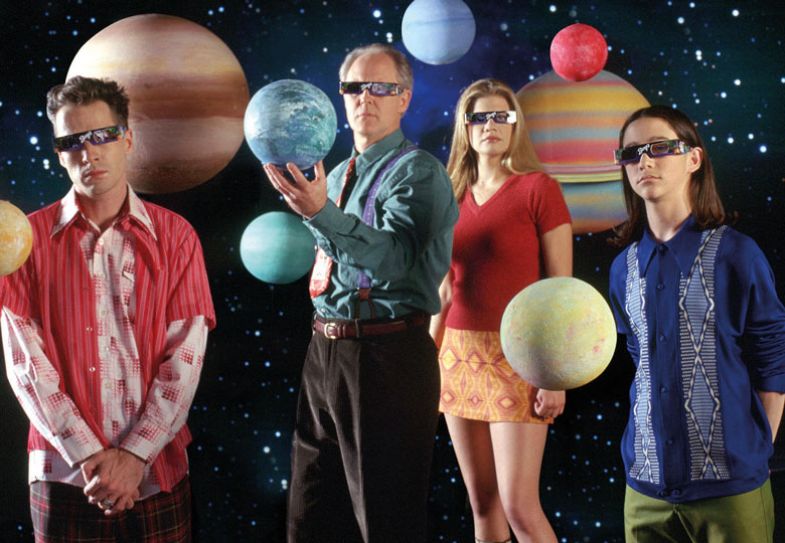

A position in academic physics might seem an unusual perspective from which to examine humanity, but the production team behind NBC’s 3rd Rock from the Sun (1996-2001) ran the experiment anyway – and garnered stellar reviews along the way.

For those unfamiliar with the series, 3rd Rock follows the adventures of alien high commander Dick Solomon (John Lithgow), security officer Sally (Kristen Johnston), information officer Tommy (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and their transmitter Harry (French Stewart). The aliens are on a benevolent participant-observation mission to Earth to study humanity and, to accomplish that, Dick chooses a job teaching physics at the fictitious “third-rate” Pendelton State University in central Ohio. Over the course of six series, this setting allows 3rd Rock to critique a variety of sociocultural norms from a socially progressive perspective, promoting equality and inclusion, and deriding discrimination in any form.

Much of the reason why Dick works as a character is Lithgow’s performance, matching the heights of Dick’s arrogance and brilliance with the depths of his confusion about and affection for humans in general and, in particular, for his colleague, anthropologist Mary Albright (Jane Curtin) – all the while maintaining an undertone of childlike innocence befitting an alien pretending to be human.

However, Solomon is more than just a dazzling comedic turn – it’s arguably one of the most enduring and influential depictions of an academic in modern times. That is partly thanks to the ubiquity of 3rd Rock on American and transnational television. In his 2005 book Rerun Nation, Derek Kompare noted that reruns are a key part of how national identities develop, and I would argue that they help to construct a variety of identities for viewers. While not everyone may have the chance to get to know university professors on a personal level, anyone can get to know and emotionally engage with a fictional professor like Dick. While the audience understands that they are watching a fictionalised, arguably hyper-realised representation (in which Lithgow’s character is also performing a role), they recognise that the comedy is likely based on some elements of truth.

That is why Dick is so important. Even though he is clearly unreal, he represents both the best and worst of academics to viewers. He doesn’t do any work but does deride work done by his colleague and rival Vincent Strudwick (Ron West). Instead, he is shown teaching the same group of students (over several years) in most episodes, and is explicitly shown to be a terrible teacher. That failure is (satirically) presented as a positive – as Tommy points out, the aliens are not allowed to interfere with human civilisation, so Dick’s inability to teach even basic physics prevents any of the students from learning the level of science required by the aliens’ spacefaring species. But the fact that an entire episode in series six, “Why Dickie Can’t Teach”, is devoted to this issue illustrates just how closely tied the ideas of academia and teaching are. Dick’s failures and arrogant pettiness with regard to his job remind the audience what an academic should be, at least from the perspective of the production team.

But for all his academic failings, the viewer still warms to Dick’s prickly charm and childlike fascination with and enjoyment of learning new things about humanity. I often tell students that the best researchers are like children in that they continually ask “why?” and “how?” about everything under the sun, critically analysing assumptions about cultural norms and received wisdom. If that is not the most important part of academia then I am not sure what is.

Melissa Beattie is an independent scholar based in the US. She has written about 3rd Rock from the Sun in a recent book from Palgrave Studies in Science and Popular Culture, titled Academia and Higher Learning in Popular Culture.

A toothless squirrel

I remember exactly where I was the first time I met Pnin. In my early twenties and toying with the idea of trying for an academic career, I still read campus novels to give myself fair warning about university life. Set in the fictional Waindell College, Nabokov’s 1957 novel follows the quotidian mishaps of a bald Russian refugee, Pnin, whose apparent optimism and good humour belie a history of loss. But that is not what I recall from my first encounter with the book. I was riding the subway home from classes one evening when I read an early scene in which the ever-homeless Pnin introduces himself to a potential new landlord. “I must warn,” he tells her: “will have all my teeth pulled out. It is a repulsive operation.”

I laughed so loudly that the other passengers stared.

Two decades later, as I reread Pnin, the novel comes as a shock. Maybe it is the fate of the young to resemble old people they once laughed at, but I now see myself in Pnin. “His life was a constant war with insensate objects that fell apart, or attacked him, or refused to function,” writes Nabokov. I reflect on my recent attempts to make my laptop plug work despite its bent prongs, or my ongoing battle with the motion-activated floor lamp in my office. It turns off automatically when I am immobilised in Zoom meetings, forcing me to wave my arms wildly out of the dark.

Then there is Pnin’s teaching style, characterised not so much by pedagogic savvy as by well-placed digressions. Like him, the longer I teach, the more I rely on stories. Pnin amuses the sprinkling of students in his Russian classes with “nostalgic excursions in broken English” and “autobiographical tidbits”, like the time he came to the US and failed the entry test. Asked if he was an anarchist, Pnin wanted to know what kind of anarchism the officers meant – “anarchism practical, metaphysical, theoretical, mystical, abstractical, individual, social?” The result was a two-week stay on Ellis Island.

As a teacher of English literature in Germany, I often find myself struggling to convey the rich intertextual allusions and cultural references in our texts. My students know an impressive amount about contemporary Anglo-American culture, but there are gaps I cannot fill. And here is Pnin, standing before his students, recognising that he will not convey the wit of 19th-century Russian comedy: “To appreciate whatever fun those passages still retained one had to have not only a sound knowledge of the vernacular but also a good deal of literary insight, and since his poor little class has neither, the performer would be alone in enjoying the associative subtleties of the text.”

As the novel progresses, Pnin is drawn further into sombre memories of his exilic past. While giving a lecture he thinks he sees his parents sitting in the hall, long dead of typhus, along with friends murdered in the Russian Revolution. A visit from his cheating, manipulative ex-wife, Liza, transports him to Paris and their escape from wartime Europe on Nansen (stateless persons) passports. Deep into the book we discover his truest love, Mira Belochkin, killed at Buchenwald, for whom he still feels “a pang of tenderness…akin to the vibrating outline of verses you know but cannot recall”.

This should be an unbearably sad book. Pnin’s losses, tallied up, seem too great to mourn. They are rendered more poignant by the relentless vitality of his mediocre New England college, with its “murals displaying recognisable members of the faculty in the act of passing on the torch of knowledge from Aristotle, Shakespeare, and Pasteur to a lot of monstrously built farm boys and farm girls”. Pnin’s colleagues, unburdened by the weight of history, busy themselves with petty office rivalries and grant-funded research trips to Cuba.

But Pnin – and this is his enduring charm – seems determined to have a future. He learns to drive, even if he does not drive particularly fast or unidirectionally. He throws “a little house-heating soirée” for a home he will soon lose. And unlike his politicking colleagues, he can still lose himself in his scholarly work. The narrator’s portrait of Pnin poring over a library catalogue drawer with the concentrated satisfaction of a squirrel chewing on a nut is only half satirical. He makes “a quiet mental meal of it, now moving his lips in soundless comment, critical, satisfied, perplexed”, as accurate a portrait of the delicious absorption of research as any I know.

Finally, after he has lost almost everything, Pnin refuses a degrading offer to continue working at a university that holds him in contempt. Our last sight of him is in his little car, driving away into the distance, “where there was simply no saying what miracle might happen”.

Irina Dumitrescu is professor of English medieval studies at the University of Bonn.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login