When geopolitical tensions and conflicts arise, academics and university leaders often have a difficult decision to make. In cases where their country’s citizens or government – or, most likely, both – stand firmly on one side of the argument over who is in the right and who is in the wrong, the question arises of whether it is better to maintain or break contacts with peers and counterpart institutions in the “bad” country.

The case for doing so is obvious, and universities often come under pressure to play their part in sanctioning and isolating the offending nation. However, there is also an argument that the human quest for knowledge should transcend petty political squabbles – and, moreover, that since academics are often among the most liberal and open-minded people in “bad” countries, punishing them can even play into antagonistic governments’ hands.

Amid tensions between the West and Russia and China that are at their highest point for many years, and in the wake of a pandemic that severely restricted international travel, commentators are proclaiming that the tide of globalisation may be turning. If that is true, it has profound implications for universities, which have enthusiastically ridden that tide in recent decades, both in their teaching and research.

But is it true? Times Higher Education has surveyed nearly 100 university leaders from across the world about their view on globalisation and the free exchange of scientific knowledge. And their verdict is decidedly mixed.

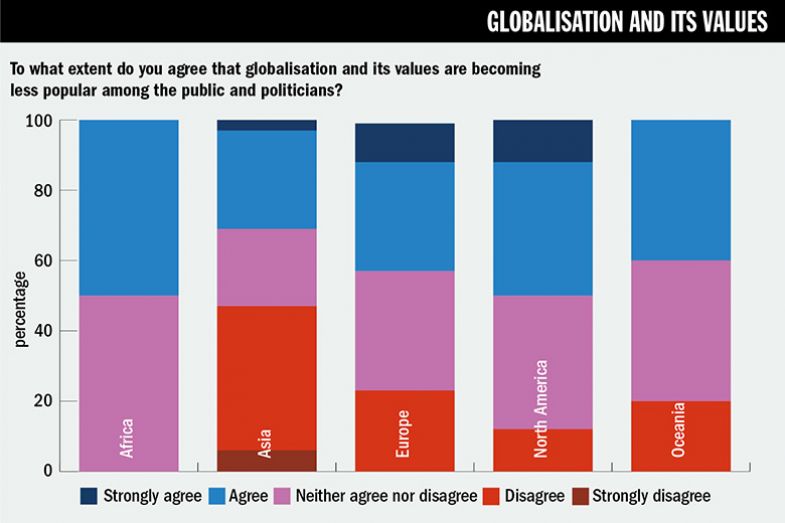

When asked if they agree that globalisation and its values are becoming less popular among the public and politicians, the 93 respondents are split: 33 per cent either agree or strongly agree, 27 per cent are neutral and 26 per cent disagree or strongly disagree.

Leaders in Europe (where 39 per cent of respondents are based, 43 per cent of whom are in the UK), North America (10 per cent) and Oceania (6 per cent) are most likely to believe that globalisation and its values are becoming less popular, while those in Asia (38 per cent) are more likely to believe they are not (41 per cent).

One university leader in Singapore highlights this global divergence, saying “our local politicians are very supportive of globalisation, but indications are that politicians in many other countries are having reservations.” And a university leader from Romania cites a common criticism of globalisation: “We must take care and respect national particularities, customs and desires. We must not transform into an amorphous mass!”

When it comes to forging global links, one of the most pertinent issues is the free exchange of scientific knowledge. That value has come into question in recent years as China has become a more powerful force in the world and positioned itself as a geopolitical rival to the US.

Under former US president Donald Trump, the Justice Department took a much more sceptical approach to university links to China, investigating professors over whether they had failed to disclose any financial ties to the country when seeking federal grant funding. The government also closely scrutinised visiting Chinese scholars from military-affiliated universities; at one point, Trump was said to be considering deporting as many as 3,000 Chinese graduate students and researchers deemed to have links to the Chinese military.

In February, the current US president, Joe Biden, announced an end to the crackdown, although some prosecutions have continued.

In the UK, GCHQ, the government intelligence agency, has warned universities about “hostile state actors” targeting British institutions to steal personal data, research data and intellectual property that could be used for their own “military, commercial and authoritarian interests”. And in February, Australian Research Council figures revealed that Australia’s collaborations with Chinese peers have nosedived in the latest funding round.

Yet university leaders still perceive public support for collaboration. While a minority of THE’s respondents (10 per cent) do not believe that the free exchange of scientific knowledge is still widely regarded as a good thing among the public and politicians, 81 per cent still believe that it is.

As well as concerns about national security, another block on cross-border collaboration is international economic competition and countries’ unwillingness to share the credit and proceeds from technological breakthroughs. This issue is raised by several leaders. Kuniko Tanioka, president of Japan’s Shigakkan University, cherishes “the notion that knowledge born in universities should be shared by everyone, including the future generation. However, more and more politicians and members of the public think that knowledge is for making money.”

Peter Slee, vice-chancellor of Leeds Beckett University, echoes the sentiment, saying scientific knowledge “is now seen as a commodity. There is little understanding of its complexities.”

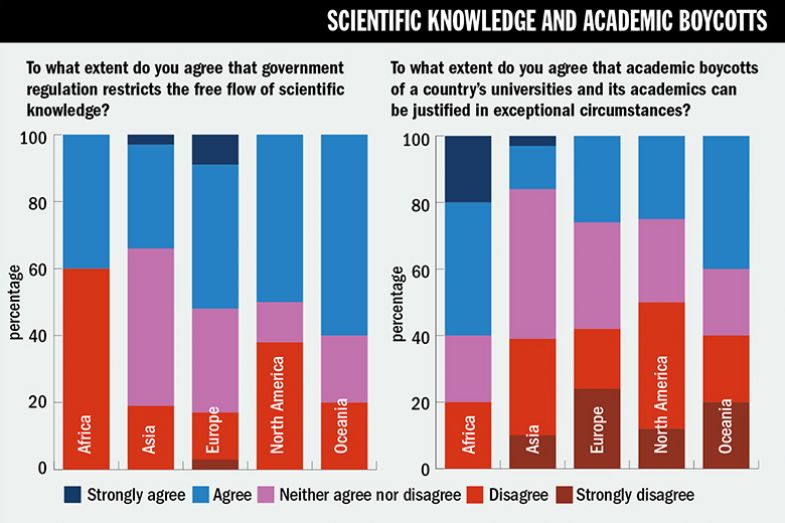

So leaders are worried about the free flow of scientific knowledge, but do they think government regulation restricts it? Forty-five per cent think it does, compared with just 23 per cent who disagree.

Leaders in Oceania are the most likely to agree that government restrictions get in the way (60 per cent). Views are more evenly split in North America, with 50 per cent of leaders agreeing that regulation is a problem and 38 per cent disagreeing. European leaders are slightly more likely to agree (52 per cent) and much less likely to disagree (17 per cent).

A leader currently based in the UK says, “The questioning of purpose behind such collaborations increases the sense of risk and can diminish appetite. This was a genuine concern when I was in Australia.”

By contrast, in Asia – where 18 per cent of respondents are from India, 15 per cent from China and 12 per cent from Japan – only a third of leaders (34 per cent) agree that government restrictions hinder the free flow of scientific knowledge.

Shigakkan’s Tanioka again cites the issue of intellectual property concerns as more of a hindrance to the free flow of ideas than government regulation.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, many Western universities and scholars cut ties with Russia. So, do university leaders believe that academic boycotts can be justified in such exceptional circumstances? The question elicited one of the strongest responses in the entire survey. Only 28 per cent of leaders agree, 4 per cent strongly, while 39 per cent disagree, 15 per cent strongly. A third neither agree nor disagree. In Asia, only 13 per cent agree.

A leader in Ireland says, “With true academic freedom, anything should be possible.”

On university independence more broadly, perceptions vary across the world, and often within nations. Asked whether they feel they have the freedom to take decisions that are necessary to secure bright futures for their institutions, most respondents agree that they do (69 per cent), but 10 per cent disagree.

Those with concerns are scattered across the globe, from the UK and Ireland to Spain, the Czech Republic, Turkey, Nigeria, Canada and Australia. One UK-based leader says, “Regulation can affect the focus in smaller institutions disproportionately. Capacity to take decisions can therefore be more limited.” Another says, “UK government hostility to higher education, to international students and to funding is a continuing problem, likely to last as long as the present government does.”

The leader in Ireland says, “Legislative constraints do not permit us to do certain things, like borrow money to develop infrastructure that is needed. Also, the funding model in Ireland is not satisfactory.”

Tanioka, in Japan, says: “Internally, I have enough freedom in the university. But the regulation of the government works towards limiting the freedom.”

This year’s figures represent a slight deterioration in perceptions compared with last year, when THE asked the same question in its leaders survey. Then, 74 per cent of respondents agreed that they had the necessary freedom to take the best decisions for their institutions. And only 8 per cent disagreed.

One decision that is often considered to be in universities’ best interests is to increase international student recruitment, for either financial or cultural reasons – or both. But do leaders predict changes in student migration after the tumult of the past few years?

Asked whether they think their institution will increase international student recruitment over the next 10 years, only 1 per cent of respondents disagree, while 2 per cent are unsure. More than half (52 per cent) strongly agree.

All European leaders expect their international recruitment to increase, although Andy Long, vice-chancellor of the UK’s Northumbria University, admits that while he believes his university’s “improving reputation” (on the back of an excellent result in this year’s Research Excellence Framework) should enable more international recruitment, “there are so many forces outside of our control now”.

The same is probably even more true regarding academic recruitment, and leaders are less confident that their institutions will recruit more international academics in the next 10 years. While 84 per cent of respondents agree that this will happen and only 1 per cent disagree, 14 per cent are unsure.

“Gradually and progressively, a general understanding is being gained about the importance of the participation of international academic staff for both teaching and research,” says a Mexican leader.

However, “The current conditions of service in Nigerian universities will not encourage recruitment of international academics,” says a leader from that country. And Shigakkan’s Tanioka warns that “mainly because of the language barrier, taking care of the foreign student takes much energy and time of the staff. Internationalisation of the campus is important, but the health of the staff is more important”.

In some countries, a threat to internationalisation is posed by ongoing border restrictions due to Covid-19 or tightened visa restrictions intended to limit immigration. An alternative to direct international recruitment, which gets around such issues, is transnational education, whereby students are taught by staff from overseas universities in their own countries. Asked to what extent they agree that their institution will deliver more of its courses as transnational education in the next 10 years, 66 per cent of respondents agree, 30 per cent strongly, while only 12 per cent disagree. Leaders in Asia and Oceania are especially likely to believe that transnational courses will grow.

And, global tensions notwithstanding, cross-border research collaborations remain firmly on leaders’ agendas for the next decade, with 93 per cent agreeing that they will form more. Such collaborations are “important for reputation and reach”, according to a UK-based leader.

The positive picture is similar when it comes to institutional-level international partnerships over the next 10 years, with 93 per cent of leaders agreeing there will be an increase, and none disagreeing.

Another factor that affects international recruitment and collaboration is the experience of others who have already taken the plunge. It has been a frequent criticism of some Western universities, particularly in high-fee countries, that while they are very solicitous in the recruitment phase for international students and staff, they are much less assiduous in making sure those they recruit are happy and successful after they arrive.

However, asked whether their institution provides as welcoming an environment as it could for international students and scholars, only 2 per cent of respondents disagree. All of the latter are from Europe; a leader from Romania admits that “we could do better”, while a UK vice-chancellor says there is “still a lot more work to do”.

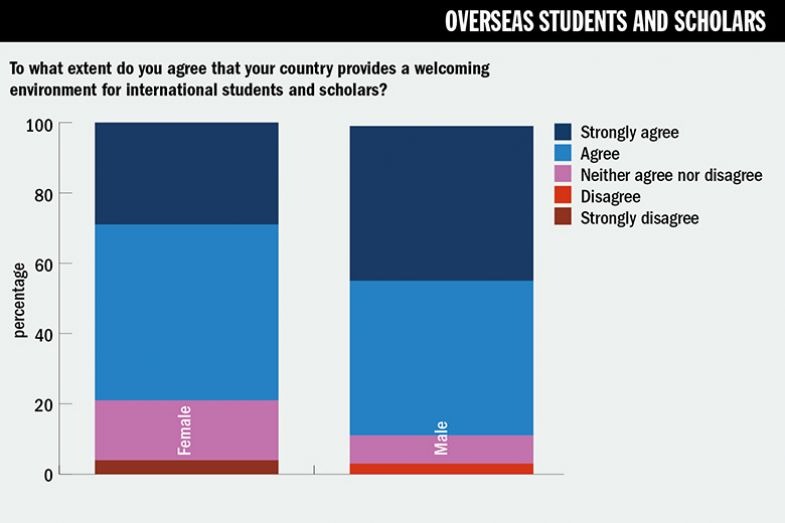

On the question of whether their countries provide a welcoming environment, leaders are slightly less sure, but 85 per cent still agree, 40 per cent strongly, and only 3 per cent disagree. Interestingly, all of the last were women who have been in post for less than a year, suggesting that younger women may have higher standards for describing a country as welcoming.

Northumbria’s Long says that he would certainly have agreed 10 years ago that the UK offered international staff and students a welcoming environment. “But the Brexit vote and, more importantly, the media narrative that surrounded it have changed things. This year, we saw the first significant media campaigns against international student recruitment, amplified by some politicians – even though their party’s stated policies promote higher education as an export.”

In other parts of the world, very different hostile actors are preventing international flows. The Mexican leader says that while Mexico has an “open door” immigration policy, “the environment of violence, due to organised crime, is hostile”.

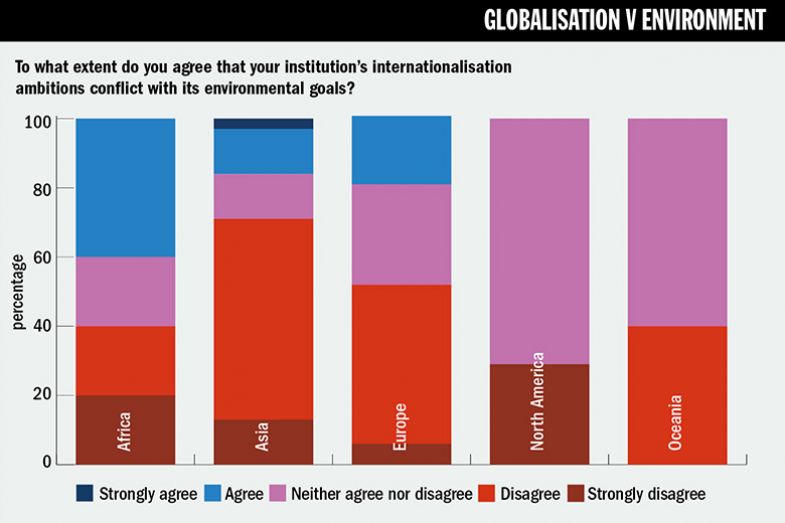

For some environmentally minded academics, a downturn in international recruitment would have a silver – or green – lining given the amount of air travel that it relies on. But only 16 per cent of respondents agree that their institution’s internationalisation ambitions conflict with its environmental goals, and only 1 per cent strongly. Nearly half (45 per cent) disagree, 12 per cent strongly.

Long says universities “have to take this argument head on and be confident that the education that we deliver and the research we conduct in collaboration with international partners will have a net benefit to the future of the planet”.

Global tensions and the climate emergency may be causing big shifts, but are they changing how leaders feel about the future of their institutions generally? While several respondents cite geopolitics and conflict as the single greatest threat to their universities over the next decade, 96 per cent agree that they feel positive about their institution’s prospects over the next five years, 60 per cent strongly. In last year’s survey, the positive response was slightly lower, at 91 per cent.

When it comes to overall student recruitment over the next five years, the differences between this year and last year are reversed, but perceptions remain bullish. Eighty-four per cent agree that they feel positive about it, compared with 88 per cent last year. Only 2 per cent disagree.

That confidence about the future is no doubt a big part of the reason why a full 97 per cent of respondents agree that they enjoy their jobs, 61 per cent strongly. No one disagrees.

“It is challenging, at times exhausting, but very satisfying when it works,” says Phil Deans, president and vice-chancellor of Richmond, the American University in London. Another UK leader notes: “I am relatively new. It is too early to have become cynical!”

Many respondents cite financial factors as the biggest threat they face in the next decade, but the worries relate not so much to student recruitment itself as to wider economic conditions and government funding trends. For instance, UK-based leaders frequently cite the declining real-terms value of the maximum fee they are allowed to charge their domestic graduates: £9,250 a year.

Domestic demographics is also a worry, with a leader in Portugal fearing a “decrease in student candidates as a result of the low birth rate in Portugal. A greater effort will have to be made to attract international students.”

Political interference is another concern, but, perhaps surprisingly, only one respondent mentions the threat to in-person education potentially posed by the rise of digital instruction during the pandemic. Commentators have suggested that this may open the door to tech firms able to offer such instruction more cheaply than universities can.

Students themselves, of course, have generally expressed a preference for a return to in-person teaching, but leaders’ opinion is mixed about whether this is still the most effective mode of instruction. Asked whether universities are maximising their potential to benefit their students, 82 per cent of leaders agree, 40 per cent strongly. But some respondents clearly feel there is room for improvement, with 6 per cent disagreeing.

A leader from the UK says, “We work hard to do this but there is too much regulation, which limits scope for agility.” The leader from Ireland says their university needs “better facilities”.

Shigakkan’s Tanioka is more upbeat: “I do not know a university which tries harder than our university to maximise the benefit to students.”

“Quality of teaching” is by far the most common response when leaders are asked what the highest priority of their office is, cited by 24 per cent of respondents – compared with 14 per cent for “quality of research” and 11 per cent for both “student satisfaction” and “internationalisation”. But confidence in their student offering is evidenced by the absence of pedagogical considerations from leaders’ reflections on what the most important thing is for their institutions to achieve in the next 10 years.

Many are concerned with improving the quality of their research and recruiting more academic talent. Other targets include increasing student numbers, environmental sustainability and global reputations. But achieving financial stability, once again, figures prominently.

Leaders may largely be confident that the words and actions of belligerent global leaders won’t affect their own universities unduly, but it is clear that many are not so confident about their universities’ bank managers.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login