The world’s top universities expect to continue to thrive over the next 12 years, but foresee their curricula, funding streams, student bodies and workforces evolving significantly.

These are some of the conclusions that can be drawn from Times Higher Education’s first major survey of the leaders of universities in our World University Rankings.

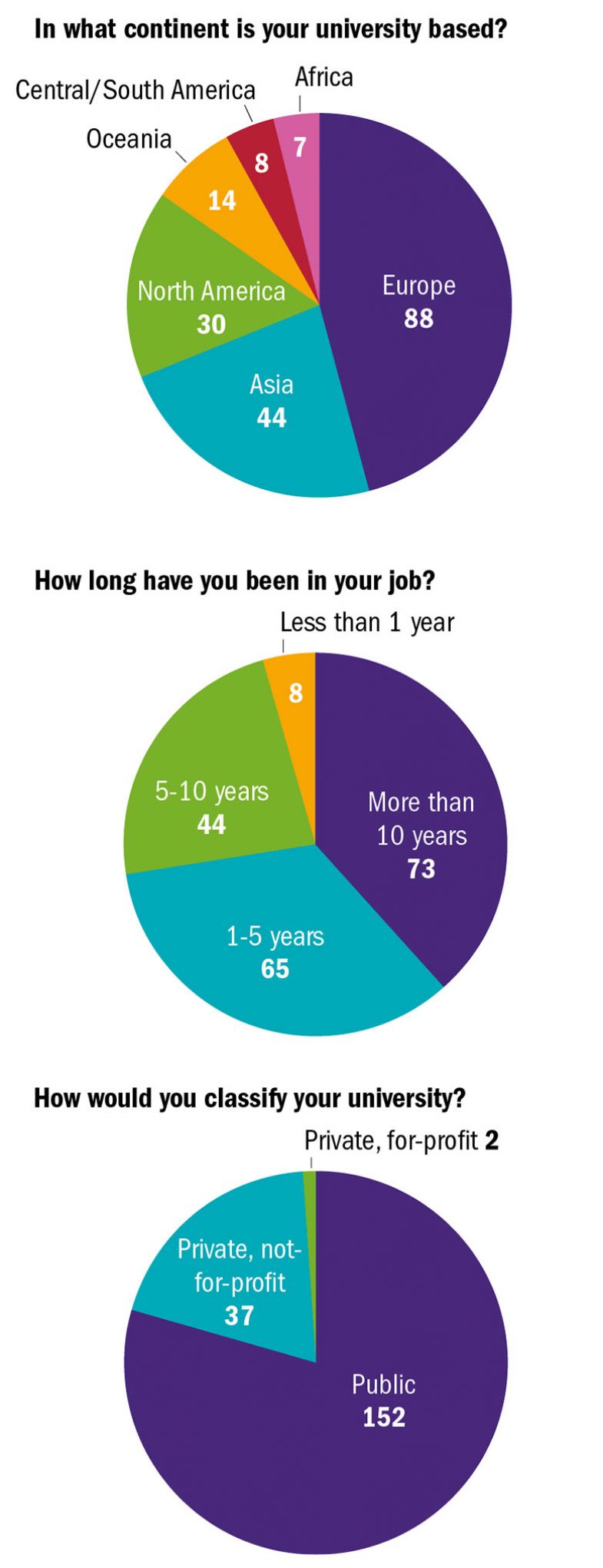

Ahead of our World Academic Summit at the National University of Singapore between 25 and 27 September, we asked university leaders a series of questions around the theme of the university in 2030. The result is nearly 200 individual insights, from leaders in 45 countries, across six continents, into the trends, threats and priorities shaping higher education nationally and internationally in the short to medium term.

Among the findings of the survey are that:

- Universities are expected to work more closely with industry, make greater economic contributions to their nations and increase their STEM provision and the proportion of their research that is applied

- No leaders expect their institutions to close by 2030, despite threats to their incomes, particularly public teaching grants

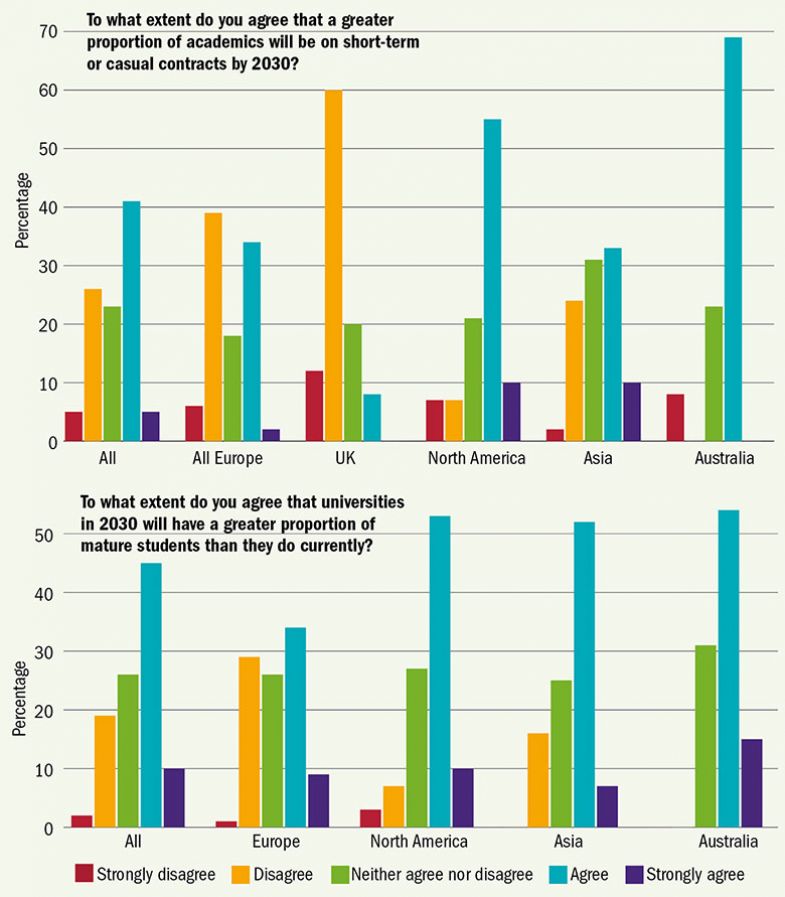

- Workforce casualisation is expected to increase, especially in North America and Australia – but not in the UK

- Mature students are likely to increase as a proportion of the student body, while the length of degrees is expected to shorten in North America and Australia.

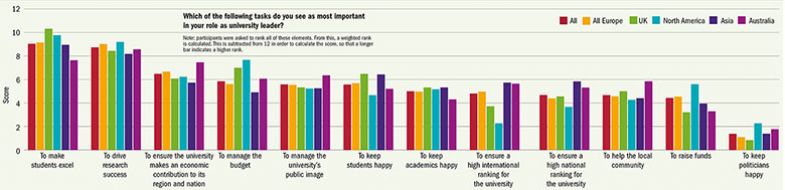

Priorities, priorities: how university leaders see their role

Central to the question of how a higher education institution should chart its course to 2030 is the issue of what a university is for. The answers, in university leaders’ minds, are clear. Asked to name their most important roles, the biggest proportion of leaders opt for “to make students excel”, followed by “drive research success”.

Making students excel is not, of course, the same as maximising their satisfaction, and some university presidents pointedly object to the suggestion that their roles include keeping students – not to mention academics or politicians – “happy”.

“Our contributions to the people and communities are of paramount importance,” says Yang Hai Wen, vice-president of Southern Medical University in Guangzhou. “In China, students who have been recruited by the universities feel relaxed. If the universities consider much about how to make the students happy, they won’t work hard and learn well.”

Funding that teaching mission, though, is not always expected to be easy. While China might be pouring money into its universities, the same is not true across large swathes of the globe.

The trust factor: will trust in universities grow?

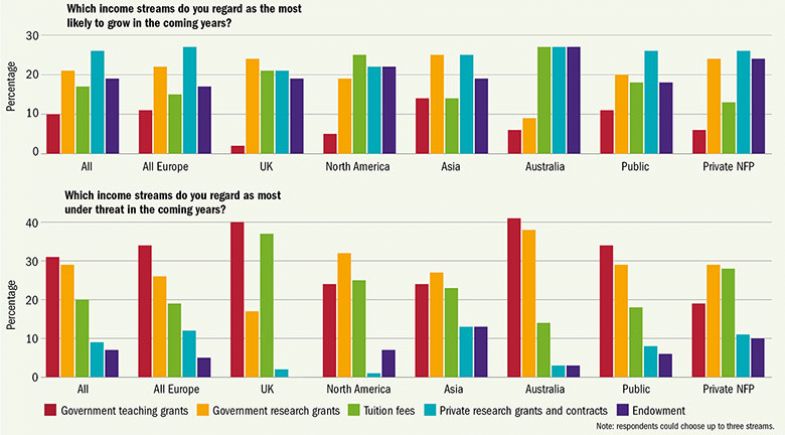

Almost half of respondents expect university teaching to account for a lower proportion of overall public spending by 2030, while only one-third expect the opposite. Teaching grants are considered the most threatened income stream in Europe, Oceania (all of whose respondents are from Australian institutions), Africa and Latin America (there were only seven and eight respondents respectively from these continents, so the results should be treated with some caution).

Tuition fees are also seen as a highly jeopardised form of revenue in North America, parts of Asia and the UK, and a mere one-10th of respondents overall say government teaching grants are the revenue stream most likely to grow in the coming years.

“There is persistently downward pressure on public spending of all sorts, particularly at the state level,” says one US university president. “Further, there is increasing public perception that higher education does not provide a good dollar return on investment, despite objective evidence to the contrary.”

Tim Sands, president of Virginia Tech, says that state support for higher education has halved over the past two decades, on a per-student, real-dollar basis, while the cost of delivery has not changed, and there is “nothing happening now that would suggest that this trend will be reversed”.

If the government won’t pay for university teaching, the individual must – and public US universities see tuition fees as the income stream most likely to grow. However, according to Sands, universities do not hike their tuition fees without considerable qualms.

“The challenge is, what kind of a university are you going to be?” he says. “Quite a few potential students from high-income families would love to be at Virginia Tech. The problem is that we’re a land grant institution, a public institution, and we try to serve the broadest population we can. The student from a lower- and middle-income family is really stretched by our net price. We’re trying to bring in more students in [those] income tiers, and in doing that we have to discount the tuition.”

Sands says Virginia Tech is relatively fortunate because it experiences high demand, and therefore only has to cut its prices for disadvantaged students. Some institutions have to offer discounts to get anybody through the door: “Hundreds of private non-profit institutions’ discount rates are starting to hit numbers above 45 per cent or so, [but] if they don’t have a large endowment they’re really struggling to find students who can pay even the heavily discounted tuition fee rate.”

Who and where: the respondents

Gloom about teaching funding reigns elsewhere in the Anglo-Saxon world, too. According to Brian Schmidt, vice-chancellor of the Australian National University, there is a “strong need” for a greater share of Australian public spending to be dedicated to higher education teaching. “But the political will seems unlikely to materialise,” he adds – although “[it is] hard to know exactly what government will do in this age when the politics of the day trumps long-term policy”.

Fellow Australian vice-chancellors have dim views of politicians’ motivations. “Our government has absolutely no idea how to create a dynamic and innovative society to drive national prosperity,” one complains. “They regard higher education as a cost and a political football opportunity.”

Another perceives “no political appetite to increase per-student spending, and any volume growth is likely to be moderate”.

UK university chiefs also cite recent trends, expenditure priorities and an unfavourable political climate in explaining their pessimism about the prospects of a boost in teaching funds.

Money matters: universities’ projected income streams

Elsewhere in the world, the prognosis for teaching funding is more mixed. Lino Guzzella, president of ETH Zurich, is not optimistic, noting that “although I would like this to happen, the trend [in Switzerland] goes more towards less support for academic and high-level education”. But in neighbouring Germany, all but one out of six respondents expects a higher share of the country’s GDP to be devoted to university teaching.

Chinese institutional leaders are more upbeat still, with all seven respondents expecting an increased share of spending for higher education teaching. Some say accelerating economic development and rising prices mean it is inevitable.

For instance, Yang of the Southern Medical University says that the healthcare demands of “ordinary” people, coupled with Chinese president Xi Jinping’s Healthy China 2030 policy, will oblige the government to “devote more GDP to medical education”.

Elsewhere in Asia, Hassan Amir Shah, vice-chancellor of Government College University in Lahore, acknowledges competing priorities and political agendas but predicts that “demand for knowledge-based economies and international integration” will force governments to spend more on public sector education.

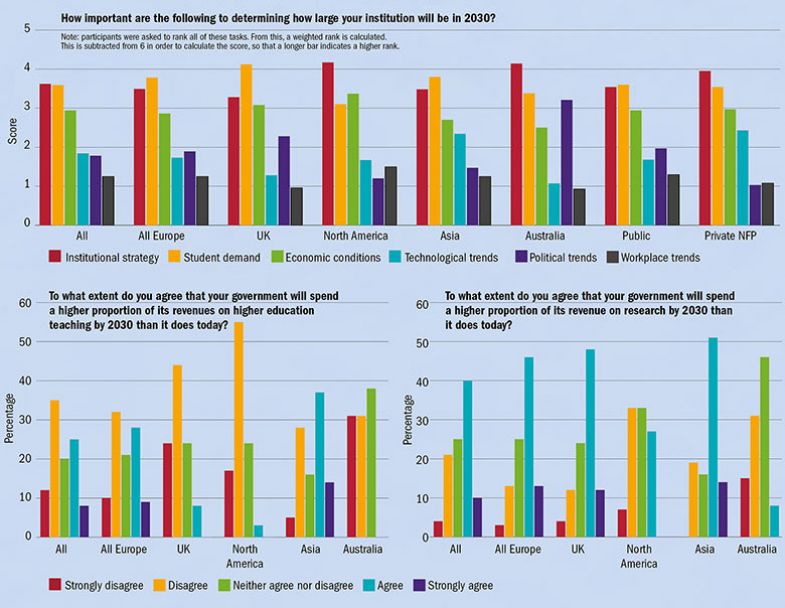

Growth factors: size matters and government support

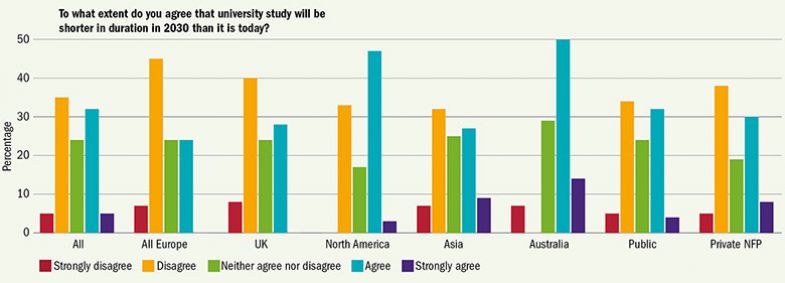

The pessimism about teaching funding may help to explain why many respondents expect the duration of undergraduate degrees to be shorter by 2030. Overall, 37 per cent do so, against 40 per cent who do not. However, the regional differences are marked. European leaders do not generally expect degree duration to contract: “If anything, it will get longer to cope with the need to broaden [higher] education to more people with poorer levels of basic education,” says Peter Slee, vice-chancellor of Leeds Beckett University.

However, leaders in North America and, especially, Australia do expect degree durations to shorten. In the case of the US, this is tied to the issue of keeping tuition fees affordable.

“Part of our work in helping students to succeed at our university has to do with making sure they understand their degree requirements” and don’t take courses that are neither necessary nor interesting to them, says one president of a US public institution. “This work is taking place at institutions across the country as we focus on helping students graduate with less debt.”

Time is of the essence: will degrees become shorter in duration?

Other leaders expect that even if traditional degrees maintain their current durations, shorter qualifications will evolve alongside them. Klaus Capelle, former rector of the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) in São Paulo, Brazil, says: “Shorter degrees and microcertifications/nanodegrees will respond to demands from society and markets. However, these possibilities will complement, not eliminate, the traditional academic degrees, for which there will still be demand.”

That demand for shorter qualifications relates to the so-called fourth industrial revolution, in which artificial intelligence and robots are expected to take over many jobs previously done by graduates, requiring the latter to retrain.

This is also one reason why university leaders on all continents expect the average age of their student cohorts to be higher by 2030; in Australia, every respondent has that expectation, while in North America only 10 per cent disagree with the suggestion. As one Australian leader puts it: “Lifelong learning will be key in the Western world.”

However, in some countries, there are also financial reasons for universities to look to mature students. In the US, for instance, “the traditional-age student population is shrinking and is increasingly [made up of] economically disadvantaged groups that will require substantial financial assistance to attend college,” says the leader of a US public university. On the other hand, the huge youth populations of some developing countries mean that the focus of universities there is likely to remain on 18-year-olds. “Given the demographic makeup of Pakistan, with current growth rate in population, the percentage of students who are mature is not likely to increase,” says Hassan Amir Shah, vice-chancellor of Government College University Lahore.

A mixture of financial pressures and the coming changes to the world of work also account for the likely rise in casualisation in the academic sector. Overall, 46 per cent of respondents expect this to occur, against 31 per cent who do not, with the expectation particularly strong in Australia and the US.

The president of a US public university says: “Elected officials regularly question the tenure system and it is cheaper to hire faculty members on short-term contracts.”

Changing faces: how will the make-up of staff and students change?

ETH Zurich’s Guzzella says that “the rising number of people in science and the reduced financial support, unfortunately, renders this trend most likely”, while the leader of a Japanese private university says that while an increase in “short-term or casual contract academics is undesirable, the university needs it for business stability”.

The leader of a US private university suggests that the American tenure system needs to be modified: “Career-long contracts are not sustainable as they do not allow institutions to be nimble and responsive to changing social needs and demands. Long-term contracts need to pivot to five- and 10-year horizons, rather than tenure.”

The leader of an Australian university adds that shifting student and industry demands mean that “universities will need to be able to adapt their workforce. Growth in the demand for learning experiences that reflect only part of a degree – a few subjects or a single subject – means that churn could be more intense, and the need for a flexible workforce more acute.”

However, the president of a North American public university notes that “if short-term or casual contracts become the norm, it will be considerably more difficult to attract qualified individuals to our faculty positions”, forcing universities to become “more competitive with regard to quality of positions”.

UK vice-chancellors appear particularly opposed to casualisation. Only 8 per cent expect more of their academics to be on casual contracts by 2030, compared with 72 per cent who do not. One notes that such a trend would “damage the sector” – but adds that “I think there may be a view that it is necessary to find ways to manage academics more flexibly on permanent contracts”.

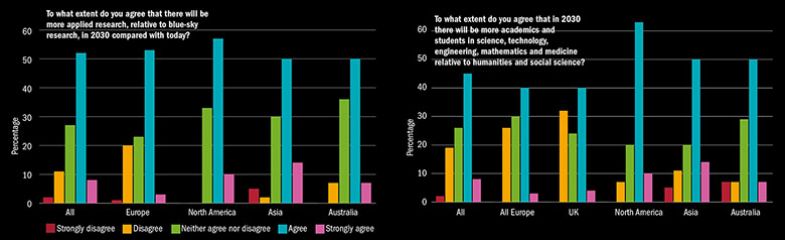

Appliance of science: what does the future hold for blue-sky research and STEMM subjects?

While the focus of the casualisation debate is often on teaching positions, many junior researchers are, of course, also on short-term contracts. Here, however, the funding pressures are expected to be less acute.

Half of our respondents believe that their governments will allocate a higher proportion of their expenditure to research in 2030, while only a quarter expect less to be allocated.

Eurasian institutional leaders are most sanguine, with 59 per cent of European and 65 per cent of Asian respondents expecting an increase. But that optimism is shared by just 38 per cent of university chiefs in Latin America, 33 per cent in Africa, 27 per cent in North America and a bleak 8 per cent in Oceania.

Australia’s vice-chancellors say that the fiscal situation and political climate militate against more GDP being directed towards research in their country. Politicians have a “flawed concept” of how research supports a vibrant economy, according to one leader – and those who understand it do not deem research a “terribly electorally appealing expenditure priority”.

Another Australian university boss acknowledges that the government plans to increase research and research infrastructure, but doubts that this will come to fruition – especially beyond medical research.

In the UK, by contrast, 60 per cent of university bosses expect the share of spending allocated to research to rise, citing promises from the government and early evidence that these promises will be kept.

One UK vice-chancellor has a simple explanation for his confidence in increased research funding: “Technological change and social problems demand it”. But another warns that progress could be tempered by Brexit’s handbrake on the economy, adding that “seed funding for true innovation is required to assure a strong pipeline of high-quality research for the future”.

Elsewhere in Europe, rectors have generally buoyant expectations for research funding, while, in Asia, the optimism is palpable. Mitsunobu Sato, president of Kogakuin University in Japan, says the share of spending allocated to research in his country will at least double. All Chinese respondents also expect to see their research funding increase; most of them are strongly of that opinion. Southern Medical University’s Yang explains why: “Research, especially innovative research, will be the most efficient way to promote economic power.”

Outside the Chinese juggernaut, however, public funding overall remains a preoccupation of university leaders. Asked to name the single greatest threats to their institutions over the next 12 years, many leaders cite underinvestment and competition for the public purse.

Political interference, policy volatility, short-termism and “government stupidity” are also high on the list, along with demographic decline and waning public appreciation, trust and awareness of science.

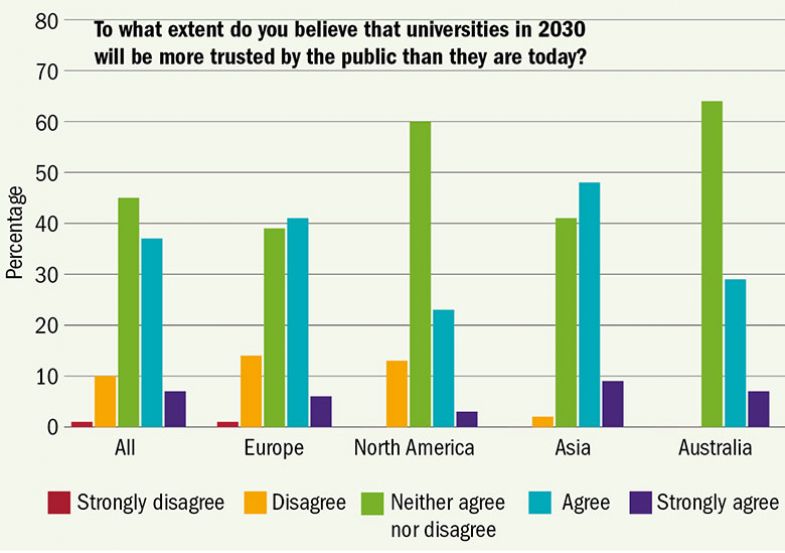

On the last point, however, 44 per cent of respondents expect universities to be more trusted by the public in 2030 than they are today, compared with just 11 per cent who think the opposite. Optimism is strongest in Asia (57 per cent agree with the proposition), and weakest in North America (26 per cent).

Other major worries include technology, overzealous regulation, lack of autonomy, rising teaching costs, an academic publishing monopoly, the cost of investment in campus real estate, the relevance and cross-border recognition of qualifications and “low-cost, low-touch, expedient degrees offered by competitors from around the world”.

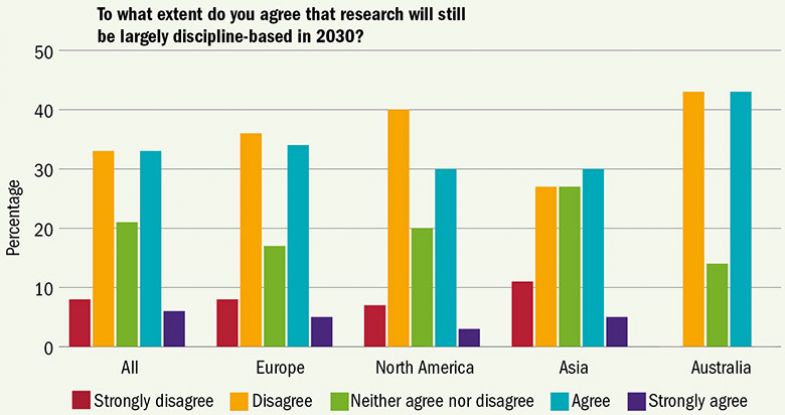

Degrees of separation: the strength of disciplines

One trend that many universities expect to transpire is that an increasing amount of their provision will be in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine.

Over half of respondents say there will be more academics and students in STEMM, relative to humanities and social science, in 2030. That view is strongest in North America, followed by Asia and Oceania.

The leader of one US public university puts the reason succinctly: “Jobs, jobs, jobs.” The president of another such institution adds that “the head-in-the-sand behaviour and entitlement of faculty in the humanities and the arts guarantees this outcome”.

Rectors in Europe, however, are more sceptical. Leeds Beckett’s Slee says such a phenomenon has been predicted ever since C. P. Snow’s 1959 lecture on the “two cultures”. But “human nature and culture override technology”, he insists. Meanwhile, Fabio Massacci, rector’s delegate for national and international rankings at the University of Trento, thinks that many students will still see humanities and social science subjects as easier and therefore more desirable than STEMM subjects: “You can rote-learn your way through law. Doing that through engineering is harder,” he says.

Ewe Hong Tat, of Malaysia’s Tunku Abdul Rahman University, says that the fourth industrial revolution will spawn occupations requiring mastery of both science and social sciences: “The trend is towards more integrated study.”

Not even STEMM disciplinarians are convinced that its ascendancy is desirable. “This is not a good outcome,” says the ANU’s Schmidt, a Nobel prizewinning astrophysicist. “The pressures of the immediate crowd out the long-term importance [of social science and the humanities].”

Meanwhile, another American university president says metrics that focus on salaries – especially salaries in the short term – tend to unduly promote STEMM degrees. “Colleges and universities must do a better job of demonstrating that graduates from the arts, humanities and social sciences live good and rewarding lives. Dollars at graduation are not the best measure of a college education.”

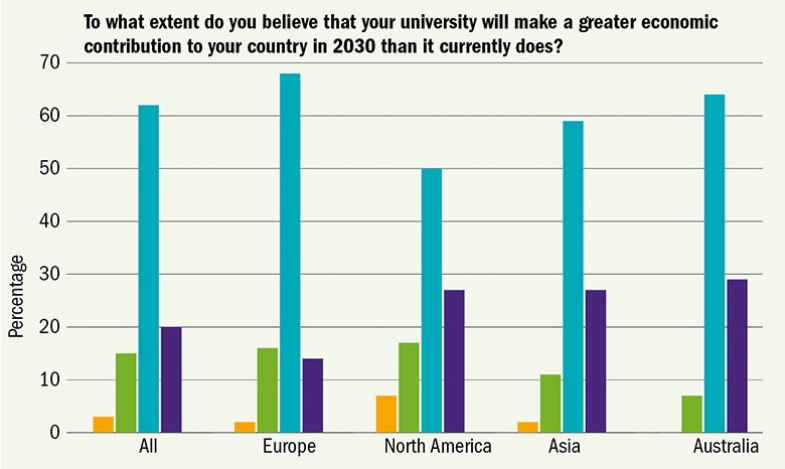

But if dollars are not the best measure of a graduate, they’re increasingly the measure of a college. Asked whether they believe their institutions will make a greater economic contribution to their countries in 2030 than currently, an emphatic 83 per cent of respondents agree, and just 3 per cent disagree.

Asked to explain their confidence, many university chiefs have simple answers. “Japan is an industry-oriented country,” offers Masato Murakami, president of Shibaura Institute of Technology in Tokyo. “Universities will become more rooted in local economies,” adds Albert van Jaarsveld of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban.

“The strong research focus of my university is in a field – economic and social sciences – where serious science [does not currently have] sufficient public impact,” observes Ernst-Ludwig von Thadden, rector of the University of Mannheim. “This will change, partly because of our efforts.”

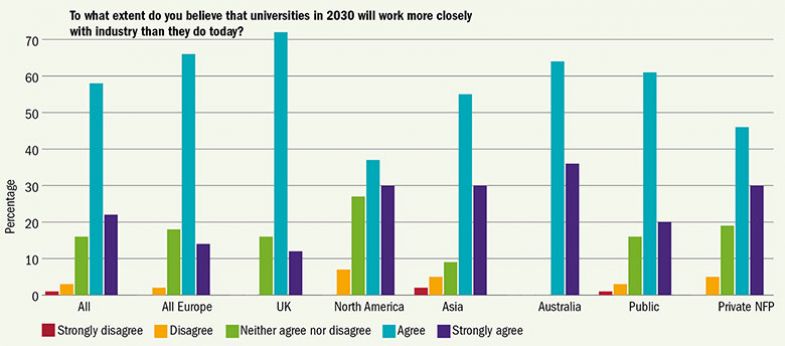

Economic drivers: contribution to the economy and industry collaboration

But if universities are expected to do more for industry, industry is also expected to do more for universities – at least in financial terms.

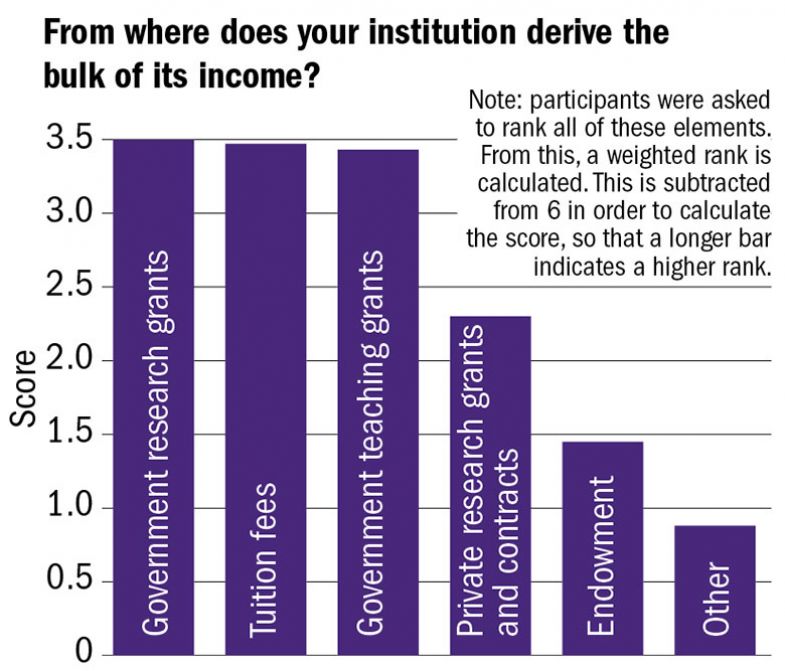

Private research grants and contracts – currently the fourth biggest source of income after government research grants, tuition fees and government teaching grants – are tipped to be the revenue stream that grows the most in Europe and Africa. They are the equal-top growth stream in Asia and Oceania and second from the top in North and Latin America. Some leaders also foresee strong growth in business activities, consultancies and commercial development of their land.

In line with this, an emphatic four in five university leaders expect to work more closely with industry over the next 12 years. Only 4 per cent expect the reverse.

“This is the economic reality,” says the head of a public US university. “Industry needs partnerships with universities to better prepare students and to perform research and development that industry no longer has the capacity to perform.”

The ANU’s Schmidt adds: “We will work closer with industry because that is where funding opportunities lie. Industry also needs our graduate talent. It is incentivised to work with universities like never before.”

Ana de Freitas, vice-rector of the University of Algarve in Portugal, sees more engagement with industry as “a natural result of the policy to improve applied research”.

Respondents are in no doubt that research is becoming more utilitarian. Three in five agree that there will be more applied research, relative to the blue-sky variety, in 2030, and just one in eight disagrees.

“Global challenges will continue to increase and compound. It is entirely possible that more research will, by necessity, need to address applied research challenges,” says one US president. Echoing that sentiment, Xu Xiaodong of Huazhong University of Science and Technology says applied research “comes from people’s needs”. People come first, he adds.

But many university leaders see the shift to applied research as being driven primarily by the search for funding.

“There is more budget available for applied research, even if we do not totally agree with this tendency,” says Luc De Schepper, rector of Belgium’s Hasselt University. “Research follows funding, and applied research is where funding is going,” echoes an Australian vice-chancellor.

The University of Edinburgh’s Peter Mathieson ascribes this trend in funding to “politicians’ short-term thinking”. Another UK vice-chancellor adds that it smacks of a “narrow approach to research and innovation” that is “linked to a funding mentality which does not appreciate the long-term outcomes, but short-term fixes”.

A Brazilian counterpart also blames “near-sighted economic and political pressure”, while a Romanian university administrator blames the younger generation, which “keeps asking for more applied teaching and research. Fundamental research will become a niche area.”

A US university leader predicts that while the trend towards increased funding for applied research will continue, particularly in the biomedical arena, “paradoxically, this may actually inhibit the development of breakthrough drugs, since applied research tends to be much more incremental”.

Mannheim’s von Thadden adds that “given the increasing complexity of science and the increasing cross-fertilisation across fields, it will become more important to understand basic principles rather than applications.”

But Martin Paul, president of Maastricht University, says the applied/blue-sky distinction is ultimately “an artificial separation which should be abandoned. Many applications have actually been derived from blue sky research.”

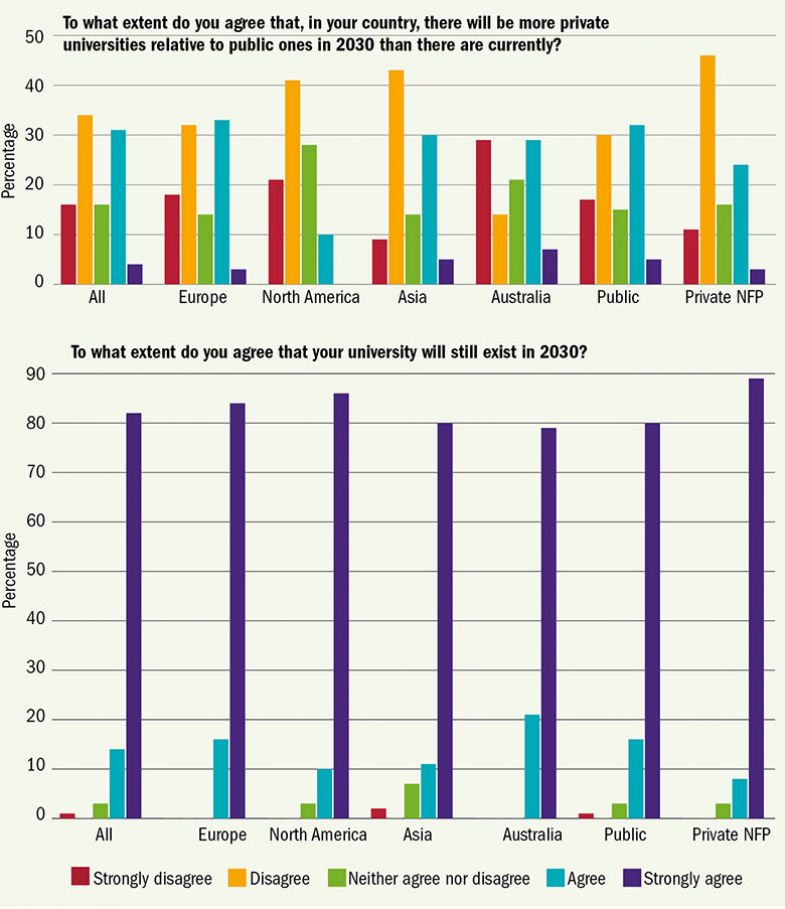

Survival strategies: how will the market play out?

Whatever the external pressures on them to move in certain directions, university leaders still believe they remain masters of their own destinies. Asked to rank the factors most likely to influence institutional size in 2030, many put economics, technology, politics and workplace trends towards the bottom of the list. Instead, institutional strategy is most frequently nominated as the key determinant of growth.

“Institutional strategy trumps all, but is of course moderated by the financial constraints,” notes the ANU’s Schmidt, while the president of a Midwestern university in the US says issues such as economics, politics and demographics are all taken into consideration “in developing and adjusting our institutional strategy to accomplish our mission”.

But in the UK, barely one-quarter of vice-chancellors place institutional strategy at the top of the list of influential factors, with most pointing instead to student demand. This factor is also considered key in Germany, where it tops the lists of two-thirds of respondents. “But [demand], of course, is strongly determined by institutional strategy,” notes Mannheim’s von Thadden.

In general, however, university leaders put such store in their strategies that almost all agree that their institutions will weather whatever storms are thrown at them over the next dozen years.

Asked whether they agree that their universities will still exist in 2030, nearly every respondent concurs – and most strongly do so. Only one Chinese leader disagrees.

Virginia Tech’s Sands suspects, however, that questions about the chances of other institutions going under would elicit different responses. He says the existential threat to US universities is “very serious” – particularly to regional public universities that “don’t have broad alumni support or the other income streams [and] that maybe haven’t developed significant partnerships across the sectors. Those are vulnerable. We’ve seen a bit of that in states like Illinois, where they’ve had a higher education funding crisis. The institutions haven’t closed [down], but they’ve gotten really close.”

Sands expects the next recession to be “a big weed-out scenario” for public and private institutions alike. While each of the last four recessions was “different in detail…each one of them has had about the same impact in terms of the financial loss to the institution”.

And since the effect of recessions on state funding levels tend to be cumulative, the inevitable next recession could be the last straw. “State funding typically doesn’t come back to where it was before the recession,” he notes. “It comes back part way, but it does not recover.”

So while the world’s top universities may continue to sail on through whatever storms may assail them, smaller and less prestigious vessels may have much greater reason to fear hitting the rocks if the political winds do not change before 2030.

Note: the survey also contained questions on the role of technology in shaping the future of universities. The answers to these will be featured in a separate article in Times Higher Education next week.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login