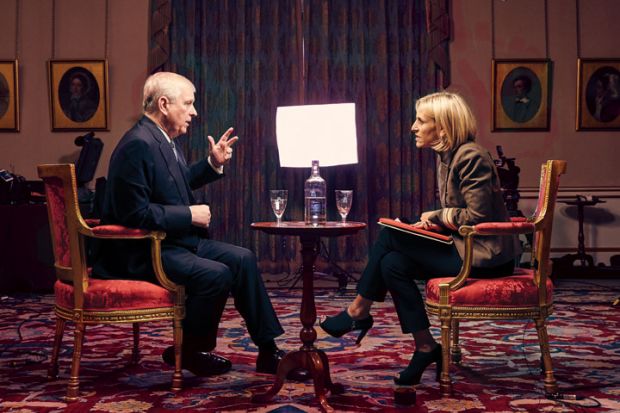

The story of how Prince Andrew came to sit down with Emily Maitlis for the interview that ended his career as a public royal is perhaps even more extraordinary than what he said (and didn’t say) during the Buckingham Palace encounter itself.

So it was unsurprising that Netflix snapped up the rights to Scoops, Sam McAlister’s candid account of how she persuaded palace officials and then the Duke of York himself to do a one-to-one that would also lead to his agreeing to make a reported £12 million payment to Virginia Giuffre over claims she was forced to have sex with the prince by his paedophile friend Jeffrey Epstein.

“It’s literally astonishing,” reflects the former Newsnight producer on the movie-length adaptation starring Rufus Sewell as Andrew and Gillian Anderson as Maitlis. “I had three months to write a book which I thought that maybe my mum, three or four other people and some PhD students researching the monarchy in 20 years’ time might read. Now my dream actress, Billie Piper, is playing me on screen – it’s absolutely insane.”

That film version will focus on the unseen events around the November 2019 interview, but Scoops is equally compelling for its insider view of how TV newsrooms work and its reflections on what makes a great interview. McAlister worked at Newsnight, the BBC’s nightly in-depth news programme, from 2008 until 2021 and describes the relentless pressure of crafting video packages and finding studio guests in a matter of hours as the clock counts down to the opening credits at 10.30pm.

“The life of a producer is a relentless hamster wheel of trying to get content, getting rejected, securing guests and content and then starting again from nothing the next day,” reflects McAlister. “Every day is fraught with anxiety because a lot of people will be watching that evening and you have to deliver a 10-minute segment or find good people to interview – your neck is on the line.”

McAlister was often described as Newsnight’s “booker extraordinaire” for her ability to secure big-name guests that bigger BBC prime-time shows failed to book. But those exclusives did not come along every week. “Interviews like Prince Andrew or Stormy Daniels are 0.1 per cent of the average content of Newsnight – the daily life of the programme relies completely on experts,” she tells Times Higher Education. “Our viewers were addicted to experts. My job as a producer was to find those experts in areas of interest to Newsnight – geopolitics, social affairs, science, education – and get them on the show.”

As a former producer, too, on BBC Radio 4’s Law in Action programme, few people are better qualified than McAlister to explain how an academic with no prior media contacts might force their toe in the door at expertise-heavy shows. But she warns that it isn’t easy.

“Most producers, if they’re desperately looking for content, want shortcuts. That means relying on someone who has been on the programme before,” she concedes. For her part, she “didn’t like that – I wanted to have different people and was willing to put in more work to get that diversity”. But the required work was not one-way. “Everything requires graft – and academics have to put in the hours if they want to get noticed,” she says.

Nor can that work be passed on to press officers. “Those press releases often look like spam that is never read,” says McAlister. “After more than a decade at Newsnight, I could count on the fingers of one hand where I’ve positively responded to pitches from university press offices.”

Instead, scholars should think strategically and use their research skills if they are serious about getting on producers’ radar. “That graft starts with identifying TV or radio shows that you need to be on and where your research will fit, and then finding those people who make decisions about content,” she explains. A scroll through the show’s title credits followed by searches on Twitter and LinkedIn are the most obvious starting places.

While academics might instinctively recoil at the idea of advertising themselves to TV or radio shows, producers are open to a well-judged pitch, particularly if it relates to a potential exclusive story, says McAlister. “You need to market yourself, which means knowing your strengths and weaknesses. You need to explain what your research is on, why it would be important to the programme and interest viewers, and why you’re the best person to explain it. Even if you are the next Einstein, you’ll need to give a good top line for any email – and the shorter, the better. Verbosity can sometimes be valued in intellectuals, but producers don’t have the time for it. Attaching a research paper is a waste of time as it will be ignored.”

Getting a succinct knock-back, or no response at all, is more than likely, but producers will not begrudge a follow-up, explains McAlister, whose book, recently published in paperback, chronicles the repeated rejections that producers themselves endure in their quest for top guests. “Most producers are very busy so you need to be persistent without becoming a pain,” she explains.

Those scholars who manage to pique the interest of a producer are, however, only halfway to making it on to the airwaves. “Emails alone won’t cut it – you’ll need to get in front of a producer. That’s often difficult but if you suggest taking them for a nice coffee – or even better a fancy lunch – they might say yes,” adds McAlister. If they do, scholars should prepare for the meeting with the same diligence as they do for a job interview, she advises: “Face to face is everything in television, so you need to show them why you are the right guest and what you’d bring to the programme.”

Those hoping to bypass producers altogether by approaching the show’s presenter directly will be disappointed, continues McAlister. “There is an idea that interviews will magically arise if you make contact with a presenter, but the truth is that 99 per cent of content comes from producers, so your relationship with them will decide if you’re on or not. So that’s where you should be directing your efforts.”

Nor does the work end there. Appearing on Newsnight – or any high-profile live TV news show – is far from a stroll in the park, as Prince Andrew learned to his cost. Scholars might be ecstatic to come into the studio, but they should think seriously about whether they are ready – or well suited – to the cut and thrust of TV news shows, says McAlister.

“Every public appearance is a cost-benefit analysis,” she says. “There is great strength in saying ‘I’m not good enough yet’ and seeking help from your press office on how you come across. You wouldn’t expect to enter the Olympics and win a gold medal if you’d never played competitive sports, but some people do convince themselves that they’re excellent on the media just because they’re well regarded by their colleagues or researchers.” Putting yourself in a “position of massive vulnerability” without adequate preparation or honest feedback from peers is a mistake, and the best university press offices will privately warn producers about poor media performers that might seem like a decent fit for a story.

That said, this doesn’t always happen, and university professors could learn from the Duke of York’s mistakes, believes McAlister, who was executive producer on the recent Channel 4 documentary, Andrew: the Problem Prince.

“He had been told he was amazing for so many years – no one was willing to tell him his answers were actually really bad, even after the interview,” she says. As Scoops explains, the Duke of York was “euphoric” afterwards, even inviting Maitlis to join the royal family for their weekly cinema club that evening.

“Unfortunately, that same dynamic is often [at play] in the hallowed halls of academia,” McAlister says. “When was the last time that a professor was told their lecture was boring or their last interview went terribly? It usually doesn’t happen.”

But there is no such reticence among producers once a show has gone to air, she explains. “Every contributor will literally get graded. The next time a producer asks about them, they’ll be told ‘They were 6 out of 10’, or ‘They were an 8 but difficult to deal with.’”

Being rude to producers for asking basic questions about a story is a sure-fire way to not get invited back, continues McAlister, a University of Edinburgh law graduate who had to brief lead presenter Jeremy Paxman on everything from the intricacies of neo-Keynesian economics to the latest ructions inside Northern Ireland politics during her time at Newsnight.

“A producer is not an expert but they might need to brief a presenter so might ask questions that are annoying, even ridiculous. If you show your irritation with a producer – and people do – you will never be invited back,” she says. While certain prickly academic guests referred her to written papers, McAlister was charmed by one Nobel prizewinning economist, who patiently answered all her questions. “He told me never to apologise for asking dumb questions, adding that if he couldn’t explain these questions then the failure was on his part,” she says. “In short, don’t make people feel small.”

McAlister’s insights into why some interviews make compelling viewing while others, despite brilliant inquisitors and intriguing guests, fall flat is one reason why Scoops should be required reading not just for media insiders but for anyone thinking about a media appearance. For instance, a long-sought interview she arranged with Julian Assange when he was holed up in Ecuador’s London embassy was a complete let-down, she admits, because the Wikileaks founder insisted on just 10 minutes of airtime and blustered his way through it, refusing to waver from his narrow talking points. And even Paxman, arguably the UK’s greatest political interrogator, blew a hard-won and potentially sensational interview with Paul Flowers, the Co-operative Bank chairman and Methodist minister filmed buying cocaine not long after his resignation from the bank over a £1.5 billion black hole in its balance sheet, by failing to ask him questions about allegations involving male prostitutes, McAlister believes.

For academics entering the Newsnight cauldron, it is vital to anticipate what questions or counter-arguments will come your way, advises McAlister. “It’s easy to know what you think but it’s harder to think of what the other person is going to say. I used to teach schoolchildren how to debate by asking them to describe one of their favourite things. Then I’d ask them to put forward three arguments against that position. You have to think about follow-ups and arguments of your adversary, which involves listening carefully to what they’ve said – if you don’t, you’ll look like you’re falling back on generalities or talking points.”

Having some zinger lines in your back pocket might also seem like a smart move, but interviewees should make sure they answer the question first as viewers are quickly irritated by soundbites. “If you’re not going to engage with the questions properly then don’t put yourself in this kind of national forum,” says McAlister.

Academics should also consider how they might “leave a piece of themselves” in the discussion to avoid things becoming too dry or intellectual, she says. “A news programme might have 20 or 30 people being interviewed, so you need to work out how to make your mark. That might mean showing a bit of your character, describing the circumstances you’ve found yourself in recently or just something interesting that will set you apart. While academics are there for their intellect and expertise, you are still trying to create a connection with the viewer or listener – the best way to do that is to show you are really a person whom people can relate to in different ways.”

Even if prestige news programmes’ viewing figures aren’t what they were a decade ago, getting an appearance right can lead to kudos from colleagues, students and friends, along with invitations to return for repeat appearances. In some cases, TV shows and book deals follow. But a fumbling performance is now liable to rattle around on Twitter for years to come, seized on and weaponised by ideological enemies. And, as Prince Andrew will attest, the fallout from a real car-crash of an appearance can be immense.

Reading Scoops is one way an academic can minimise the chances of that happening to them.

POSTSCRIPT:

Scoops: The BBC's Most Shocking Interviews from Prince Andrew to Steven Seagal (OneWorld Books) by Sam McAlister is out in paperback.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login