As 2021 progressed, many university presidents and vice-chancellors were starting to breathe a sigh of relief as the green shoots of recovery in international student mobility finally seemed to be taking root after the pandemic brought the shutters down on most international travel.

The early indications for the 2021-22 academic year in some key northern hemisphere recruiting nations suggest that there has been a strong rebound in recruitment, and November’s release of one of the first harder datasets, the Covid-19 snapshot survey produced by the US-based Institute of International Education (IIE), was the clearest sign yet that mobility could be approaching pre-pandemic levels.

However, while universities in the US, Canada and the UK dared to hope that they are emerging from the storm, those in nations where borders have been slower to reopen, such as Australia, face a much more anxious wait. Although a decision was taken by the Australian government to ease travel restrictions just in time for the new academic year, many students may have already diverted their applications elsewhere. And the emergence of the Omicron variant in late November has threatened a further spanner in the works of this attempted reopening, reminding us that travel restrictions can still be reimposed in a matter of hours.

So what is the current state of play in Australia and the other major recruiting nations for international students? Could some of the tectonic shifts that we have seen over the past two years in student flows now be solidifying into something that damages recruitment in the southern hemisphere more permanently? And what other factors are going to be important for students choosing a study destination if and when Covid finally recedes and travel fully opens up again?

We take a look at the most recent data on mobility, including student visa issuances, sector-wide surveys and individual university recruitment figures to get a sense of where cross-border study is and where it might be heading as Covid continues to cast a shadow over the sector.

Australia

The announcement by Australia’s federal government in November that those travelling on student visas would once again be able to enter the country without special exemptions provided they were vaccinated was the green light that universities in the country had been waiting for after nearly two years of closed borders. However, the extreme fragility of the situation was brought into stark relief by the emergence of the Omicron variant and subsequent decision, with barely 30 hours’ notice, to delay the reopening by a fortnight. The plans – also complicated by Australian states’ own rules around quarantine and concerns about airport capacity – were also made just weeks before the start of the new academic year, raising questions about whether the announcement was too little too late, given that many students would already have made plans to study in a different country.

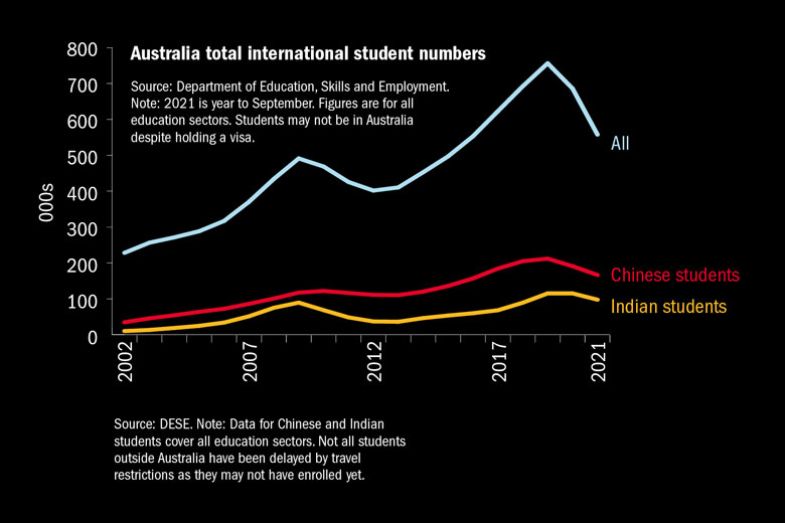

According to statistics on student visa holders studying at Australian institutions, the total number of international students who studied at some point from January to September 2021 was almost 560,000. This figure, which includes those outside the higher education sector, represents a 17 per cent fall on the same period in 2020. This may not be hugely different from the experience of other anglophone systems, but the real problem for Australia becomes clear when you scratch beneath the surface of these data.

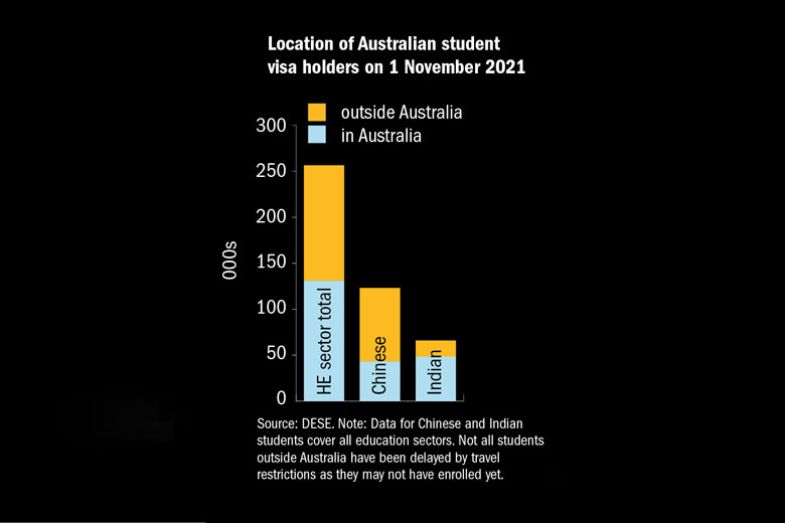

Crucially, the figures include students who have a visa but are nevertheless stuck offshore and forced to study remotely. According to data from the federal government, exactly half of the roughly 260,000 people holding a valid student visa for the higher education sector in November 2021 were outside Australia. In the case of Chinese students, the most numerous overseas cohort at Australian universities, around 120,000 held a valid educational visa, but about two-thirds of them were outside Australia. Couple that with the likelihood that many visa holders will be students who were already on multi-year courses – and so naturally would want to continue in any way they can – and it becomes clear that Australia’s main issue is how many new students are choosing it as a study destination.

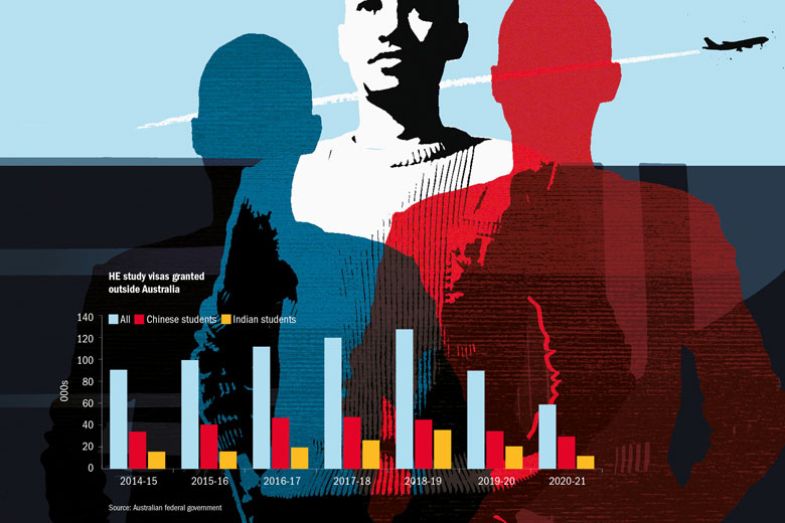

One set of data that may make worrying reading for Australian universities is the number of new student visas granted outside Australia over the past two years, which has been on a clear downward path. The total number of visas issued in 2020-21 (up to the end of June 2021) was down 34 per cent year-on-year, with those granted to Indian citizens seeing an even bigger fall of 43 per cent. There was a smaller (14 per cent) fall in the number of new visas for Chinese citizens, but the first quarter of 2021-22 (July to September) saw these drop by more than half compared with the same period in 2020.

It remains to be seen whether the changed signals from Australia – borders finally reopened to international students on 15 December – managed to reverse this trend in time for the 2022 academic year, beginning in late January. The government’s launch of a new international education strategy in late November, with a beefed-up offer on post-study work rights, shows it is well aware of the situation it needs to reverse. But the fear will be that the clear decision by thousands of students to stay away from Australia in the short term could translate to a long-term diversion of international students to other countries as word-of-mouth recommendations from former students dwindle.

The UK

Unlike Australia, the UK never really closed to international students. However, while it did not impose major border closures, the relatively high prevalence of Covid-19 in the country – alongside government policies around testing and quarantine – has made travelling more onerous and may have affected students’ willingness to undertake it. Initial lockdowns in Europe also led to the UK’s student visa services overseas grinding to a halt in the spring of 2020.

The effect was to truncate international student recruitment in 2020-21, with many students from popular destinations such as China and India starting courses later in the year or keeping to an autumn enrolment but studying online initially. Others may have remained online for the duration of 2020-21.

Although the data on UK enrolments for 2020-21 do not differentiate between start dates or how long students stayed online, they do show that overall the sector managed to avoid the major losses in overseas recruitment that were initially feared at the start of the pandemic: in total, there were 4 per cent more new entrants from outside the UK in 2020-21.

But there was a clear shift in country of origin, with entrants from India rising 27 per cent and those from China falling 5 per cent. There were mixed fortunes for universities too: among large research-intensives, the University of Glasgow boosted non-European Union enrolments by 40 per cent and the University of York by 32 per cent. Conversely, the University of Liverpool (which has strong links to China through the joint-venture Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University) and Newcastle University saw drops of 18 and 15 per cent respectively.

Visa data and statistics for undergraduate applications from admissions body Ucas also give a good indication of how international numbers may be shifting into 2021-22. For instance, the number of student visas issued has seen a major bounce back. The 430,000 granted in the year to September (including those for dependants) is the highest annual number on record.

Another unusual aspect of the latest figures is that the bulk of the visas were granted very close to the start of the academic year: September 2021 itself saw 140,000 visas issued, more than double the number in September 2019, before the pandemic began. There has also been a continuing shift in countries of origin. While China remains the biggest source country, with 135,000 student visas issued to its nationals in the year to September 2021, that 13 per cent increase on the year to September 2019 is dwarfed by the 197 per cent increase in visas awarded to Indian students, taking their total issued to more than 90,000. Meanwhile, Nigeria saw a 368 per cent increase, from just under 8,000 in the year to September 2019 to almost 37,000.

India and Nigeria are among the nations that the UK wants to target as part of its international education strategy, announced in 2019, which is seeking to grow overseas student recruitment to 600,000 by 2030 – a figure that, arguably, has already been met. Comparing the UK’s visa figures with those of Australia, where there has been a large downturn in visas issued to Indian nationals in particular, suggests that countries like the UK may have picked up some of that demand.

One reason why the UK may have a particularly keen interest in boosting its international recruitment from countries such as India is the effect that Brexit has had on the number of students coming from the European Union. Acceptances of EU students on to undergraduate courses at UK universities plummeted by 56 per cent in 2021-22 compared with the year before, according to Ucas, with a major reason likely to be that they are the first cohort to face international fees and to be denied the same access to student finance as UK domestic students.

Most EU students, apart from those from the Republic of Ireland, also now require visas to study in the UK. The data on these show that only 20,000 were issued to students from the EU and other single-market members, such as Switzerland, between last January and September. Given that 60,000 EU students started UK courses in 2019, that again indicates a major fall in recruitment from the European continent.

The US

The US has published the most detailed early data of any northern hemisphere country on international student recruitment for the new academic year. The IIE’s 2021 enrolment snapshot survey, involving the recruiters of about 60 per cent of the country’s international students, shows new enrolments bouncing back strongly from 2020. The 860 surveyed institutions reported a 68 per cent increase in international entrants, compared with complete sector data showing a 46 per cent decline from 2019 to 2020.

However, the magnitude of the bounce back needs to be set in context, for a number of reasons.

First, although there has been a big increase in new enrolments, this is from a relatively low base, owing to the major downturn in 2020. The overall numbers suggest that, unlike the UK, the US may not quite have recovered to pre-pandemic enrolment levels just yet.

For instance, the IIE snapshot says the total number of enrolled international students at US universities increased by 8 per cent this autumn, but the IIE’s Open Doors report, which gives comprehensive figures for the previous academic year, recorded a 17 per cent fall in total enrolments, from about 850,000 in 2019-20 to around 710,000 in 2020-21. Applying an 8 per cent uplift to this (assuming the snapshot figures are replicated across the sector) would leave total international enrolments at almost 770,000 in 2021-22, still a long way down on 2019-20.

Second, in response to the fact that thousands of international students have been forced to study online from their home countries during the pandemic, the IIE has begun including distance learners in its figures. It says that at least 65 per cent of the international students reported in the 2021 snapshot were on campus in the US, a higher proportion than the 47 per cent who took classes in person at some point during autumn 2020. However, this leaves the potential for a significant chunk of students to still be studying offshore, for reasons ranging from travel restrictions to concerns about the continued prevalence of Covid on US campuses. As in Australia’s case, that may not be an experience that lends itself to sustained recruitment in the longer term.

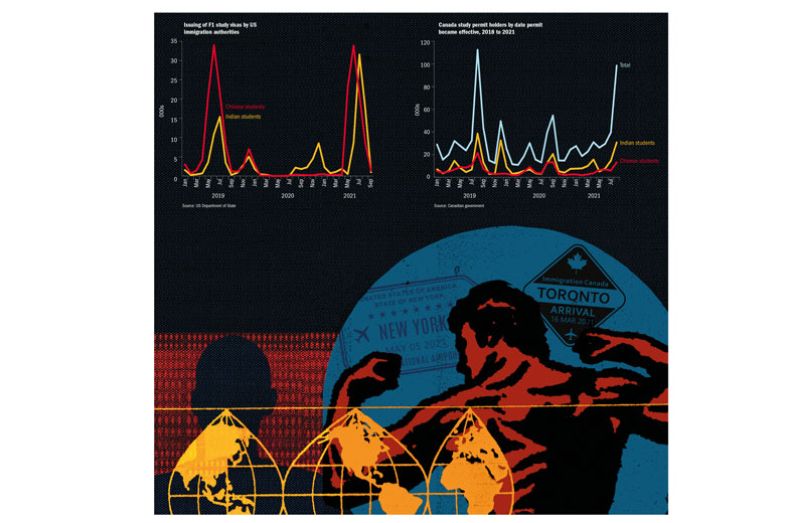

Third, the IIE snapshot does not provide a breakdown by country or institution. Open Doors reported a fall of 15 per cent in 2020-21 enrolments from China, which is still the biggest source nation, sending 317,000 students; numbers from India saw a slightly lower fall of 13 per cent (to 168,000). But data on the number of study visas issued by US immigration authorities over the past three years show that those nations’ students have adopted very different attitudes towards travelling to the US during the pandemic. Chinese issuances flatlined from the onset of the pandemic until spring 2021, when they rebounded strongly, but Indian students were still being granted visas throughout the intervening period, with a mini-spike towards the end of 2020.

It is also likely that any rebound will not be equally felt by all institutions, with enrolments at 20 per cent of respondents to the snapshot survey falling last autumn, compared with last year; 10 per cent of institutions reported no change. A Times Higher Education snapshot survey of universities in the top 50 of the World University Rankings also shows a mix of experiences. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, an institution with a stellar global reputation, recruitment from China continued to rise through the pandemic, with 2021-22 enrolment up 7 per cent on 2019-20 (although recruitment from India has fallen 4 per cent over the period). However, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, ranked 48th, the situation is reversed: a huge uptick in Indian recruitment this year translates into a 58 per cent rise since 2019, but its China enrolments are down 7 per cent.

Canada

Canada’s latest official international enrolment data only go up to 2019-20, a peak year that saw recruitment hitting almost 240,000, after growing 40 per cent over four years. However, a more up-to-date picture of how the country has fared during the pandemic can be obtained by examining the figures on the issuing of study permits, which international students need from institutions to travel to Canada.

The latest data, which show the number of study permit holders by the date the paperwork became effective, indicate a strong bounce back in 2021. The number of permits effective in August 2021 was higher than the number issued in August 2018 and almost as high as the record 113,000 issued in August 2019. This rebound was confirmed in a report from student recruitment platform ApplyBoard, which said in a November report that 175,000 permits had been issued in the first six months of 2021, double those issued in the whole of 2020.

What is also noticeable from the study permit data is that, as in the UK, 2020 did not see a complete stalling of visa issuances. In fact, activity in the spring and summer of 2020 still had noticeable peaks, as Indian and Chinese students received permits. This contrasts sharply with Australia and the US, where 2020 appeared to see a bigger fall-off in mobility.

However, Canada has not exactly sailed through the pandemic without any problems. A backlog in applications for study permits earlier in 2021 led to long processing times and the data bear this out: the normal winter peak in issuances failed to materialise in 2020-21, especially for key countries such as China and India, and there is a chance this may have affected autumn 2021 enrolments, especially if students frustrated by the process chose to apply to other destinations.

Two Canadian universities in the top 50 of the THE World University Rankings that replied to THE’s request for autumn 2021 data reported a fall in enrolments from China: at McGill University they were down 6 per cent and at the University of British Columbia they were down 4 per cent. But neither university appears to have suffered a major enrolment setback overall. For British Columbia, total international numbers are now 6 per cent higher than in 2019, with Indian enrolments 50 per cent higher. So while visa processing may have caused some teething problems, Canada’s general openness during the pandemic appears to have paid dividends.

Germany

Flying slightly under the radar in analyses of how international recruitment has shifted during the pandemic has been Germany. This is partly because it has historically had fewer students from outside Europe and also because its universities do not rely on international student fee income in the way that institutions in anglophone systems do. However, Germany’s international recruitment statistics show that it is not a country to be ignored.

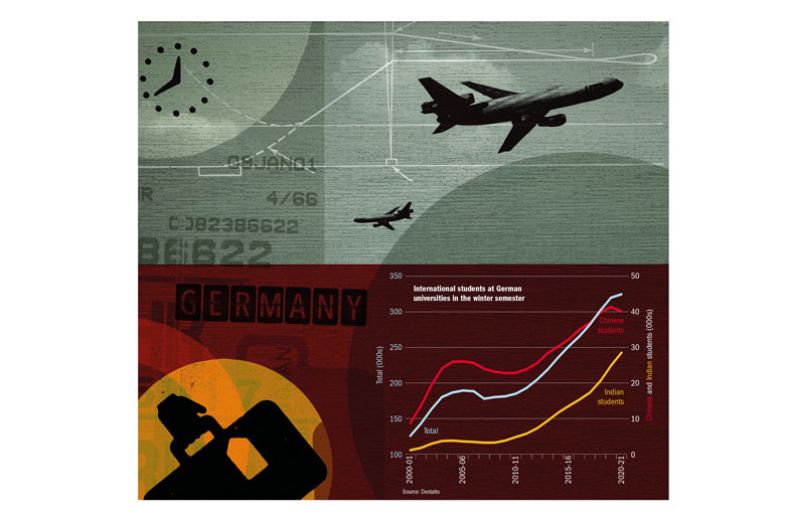

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco), more than 330,000 students from outside Germany were enrolled at the country’s universities in 2019, more than Canada’s 280,000 and not vastly far behind the UK’s 490,000 and Australia’s 510,000. Around a third of these were from Europe, with numbers from China relatively small. However, Germany has been increasing its international intakes steadily over the past decade, particularly from India. For instance, in 2010-11, according to data from the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), around 185,000 students from outside Germany were enrolled during the winter semester, with about 23,000 from China and 5,000 from India. By the start of 2019-20, overall numbers had grown to 320,000, with 41,000 from China and 25,000 from India.

Although no official data are yet available for enrolments last autumn, it is very noticeable that this growth trend has not been greatly impacted by the pandemic. In 2020-21, total international student numbers crept up by about 2 per cent, although numbers from China did fall slightly. Data on residency permits issued to students, which are needed by those from outside the EU who want to stay in Germany for more than six months, also suggest that students from India continued to travel to the country during the pandemic, while those from China seemed more reluctant. Chinese issuances dropped by about 13 per cent.

Separate data for the number of entrants starting undergraduate modules suggest a downturn in this category, falling from about 91,000 in 2019-20 to 76,000 in 2020-21. However, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) says that many of these new starters were “visiting and exchange students”, and were therefore not enrolled on German degree courses.

Jan Kercher, a senior researcher on student mobility at the DAAD, attributes Germany’s relatively robust enrolment performance during the pandemic to its decision, after the initial lockdown, to exempt international students from travel restrictions, even if they were from countries or regions with a high incidence of Covid.

“This is a striking difference to other important host countries like the US, Australia or New Zealand,” he says.

Looking to the future

The latest data on these five nations by no means perfectly encapsulate the shifts in international student mobility over the past two years. For starters, there are many more key recruiters of international students. But we can at least point to some broad trends.

“Early data, such as immigration statistics, shows the UK and Canada are performing better than countries with restricted travel, such as Australia and New Zealand,” says Janet Ilieva, founder of international mobility research consultancy Education Insight. This claim is backed up in surveys of recruitment agents, who report that the UK and Canada have been seen by would-be students “as the most open and welcoming countries”, she says – and even among the safest during the initial rollout of vaccines, in which Australia was perceived as a laggard.

However, whether this will turn into a longer-term problem for Australia and New Zealand is still open for debate. Gavin Moodie, adjunct professor in education at both the University of Toronto and RMIT University in Australia, says Australia’s border closures “may be too brief to affect its relative competitiveness in attracting international students” over the long term. But he stresses that another long-term factor driving mobility – Australia’s relations with China – could end up being “more worrisome”.

“Australia seems keen to act as the US’ proxy in confronting China and is not too big for China to consider retaliating against by restricting Chinese nationals’ enrolments in Australian universities,” he warns.

The other important aspect to consider with China, according to Anna Esaki-Smith, co-founder of consultancy Education Rethink, is that growth in outward student numbers was already declining pre-pandemic. She believes that in the short term, there may be “considerable pent-up study-abroad demand from Chinese students”, but factors such as the improvement of in-country provision in China, an ageing demographic and a slowing economy may suppress demand in the longer term.

So will countries with more favourable demographics, such as India, fill the gap for recruiting nations? The UK clearly believes that there are other nations worth targeting for growth: hence the focus of its international strategy on the likes of India and Nigeria. But as Ilieva points out, the character of student demand can vary considerably from country to country, which can have consequences for university systems. In her view, “there is no substitute for the loss of talent in subjects reliant on high-calibre students from China, such as master’s-level students studying mathematical sciences and engineering. Growth in Chinese PhD students was one of the few sources of growth in global demand for UK research degrees.”

She adds that the decline in EU students in the UK will “result in a much less diverse campus. EU students make significant academic and cultural contributions to university life.”

The Brexit effect could aid countries in continental Europe that have been slowly expanding their recruitment, especially given their low fees (Germany’s fees are zero in most of its federated states) and the growing options to study in English there. Meti Basiri, co-founder of ApplyBoard, says there is no reason why Germany and other major continental systems, such as France or the Netherlands, can’t become serious challengers to the anglophone nations, especially given the recruitment agency’s own data indicating that international students have been looking for cheaper courses because of the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, perhaps the biggest trend to watch off the back of the pandemic will be how the shift online affects future demand. As Esaki-Smith points out, it may be difficult to compare mobility pre- and post-pandemic for this reason.

“This broader acceptance of online and hybrid learning, both of which have met with considerable resistance in the past, could garner more interest from students as a convenient and often less-expensive option than the traditional study-abroad experience,” she says. “It will be important to measure a potentially larger cohort of students gaining international experiences in less traditional ways.”

In other words, the longer-term impact of the pandemic may be a major expansion in new forms of transnational education. If that transpires, the pandemics of future may pose rather less of a threat to anglophone universities’ business models than the current one has done.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Has the pandemic changed international student flows forever?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login