The greater prominence enjoyed by scientists during the Covid-19 pandemic has led to some individuals gaining a high profile – with the attendant praise and demonisation that this can bring. But these public figures are just the visible tip of a huge iceberg of effort taking place to combat the pandemic.

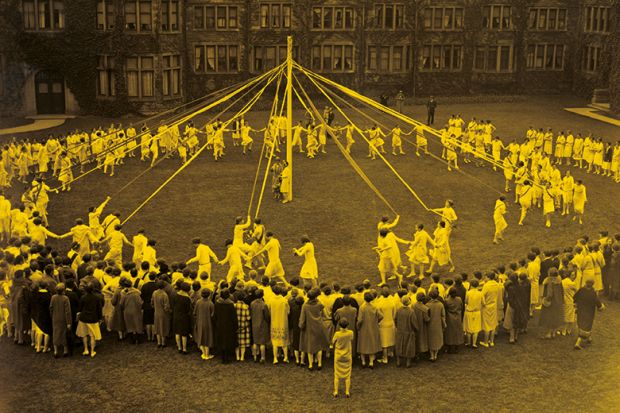

To convert one bright idea into 7.5 billion doses of vaccine will take a huge team of people. This includes not just the lab team developing and testing the vaccine, but also the animal care staff enabling the pre-clinical studies, the safety staff maintaining a safe environment to work with a potentially fatal pathogen, the lab managers ensuring that essential reagents are available, the administrators preparing the relevant grant applications, the ethics boards reviewing the trials, and the trial managers, doctors, nurses, medical students and volunteers. Not to mention the contracts team negotiating with equipment manufacturers, the accountants moving the money around, the security officers keeping the doors open and the communications experts informing the public of progress.

That is just at one institution. And the work is not performed in isolation: there are external funders, suppliers, manufacturers, regulators, toxicologists, shippers, couriers and warehouse staff, all of whom are vital to the process.

Unlike the standard image of an old white academic, staff in professional roles tend to be more diverse, with more women, more BAME and more LGBT people. But these colleagues are likely to become less international given that skilled but low-paid roles will be excluded by the UK government’s proposed post-EU new immigration rules. This would be deeply counter-productive: if the pool of skilled individuals is reduced, there will be a clear impact on the ability to deliver cutting-edge research, particularly in a time of crisis.

Highlighting the role of these critical core staff is vital. They are often under-represented in the media. For example, coverage of the recent UK pension strikes focused on the academics taking part, rather than on all the other higher education staff who shared the picket lines with them.

As well as not accurately reflecting science as a collective endeavour, a focus on individuals can, in fact, be toxic. Much of what is wrong with academia is driven by the narrative that it is a zero-sum game, where only one person can come out on top. This leads to the back-stabbing, bullying and bitchiness that characterise the very worst of our sector.

Now, as never before, kindness in the workplace is critical. Developing the vaccine that the world so desperately needs can serve as a demonstration that great things can be done collaboratively rather than competitively, belying the inaccurate depiction of it in some places as a race between different universities. In the UK’s case, the race is supposedly between the University of Oxford and Imperial College London – but the fact that some of the ChAdOx (Oxford vaccine) trials are being performed at Imperial tells a very different story.

Thinking ahead, maybe we can use this time as a trigger to rethink the whole of academia. The first step is acknowledging that it is about more than the academics. It’s been said before, but when you look at the numbers, academia is actually the alternative career for science trainees: most enter other sectors – including academic support roles. All these paths should be supported and celebrated equally.

If none of the above persuades you, then consider this. Representing the team nature of science de-risks the process for the individuals, the institutions and the ideas themselves. People sometimes make mistakes, often unrelated to the science itself, but this can tarnish the idea. In an increasingly combative media space, any perceived fault can be manipulated to damage a broader theme. Demonstrating that science is collective removes one tool from the arsenal of those that seek to discredit ideas that have universal benefit, such as vaccination or combating climate change.

The Wellcome Trust’s Reimagine Research campaign is currently looking into ways to rebalance the research space. But you don’t need to be a funder to make a difference. We can all play our part to make higher education kinder and more inclusive. Take time to say thanks. Reach out to teams outside your immediate remit. Be public in your praise, raising awareness of the whole team, not just the star signing. Applaud the whole community of effort.

Let me start by making an Oscars-style acknowledgement of some of the amazing team at Imperial (and sorry if I missed you). Thank you Kasia, Kat, Kai, K, Krunal, Kostas, Catherine, Tessa, Anna, Hannah, Hadi, Michelle, Glenda, Genevieve, Paul, Paul, Carolyn, Ruth, Jennifer, Tom, Lesley, Sharron, Jesse, Leon, Aaron and Jo.

I know that most people reading this will not know who they are, but without them none of us might ever get back to work.

John Tregoning is a reader in respiratory infections at Imperial College London.

后记

Print headline: Scientific breakthroughs: it takes a village to make the progress we need