We’re in the middle of a higher education cost-cutting frenzy – and one class of expenditure being targeted is the conference travel budget.

Before the pandemic, it was uncontroversial for universities and grant funders to help researchers attend conferences by covering some or all of their costs. But as conferences moved online during the pandemic, many people suggested that this made them more inclusive, more environmentally friendly and more time-efficient. With travel and hotel costs stripped out, conferences also became significantly cheaper.

The environmental case against academic travel is undoubtedly the most powerful. According to one estimate, aviation is responsible for about 2.4 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions and 5 per cent of global warming, even though just 3 per cent of the global population (12 to 15 per cent of people in richer countries) take regular flights. Online meetings are not carbon neutral either since broadband connections, servers and devices require significant amounts of power, but catching flights to attend short conferences is clearly not sustainable.

Does that mean all conferences should go permanently online, though? The inclusivity argument is less persuasive. The idea is that everyone around the world can attend an online conference from their home, whereas cost, disability or time may prevent them from going to in-person meetings. This conceals the technical infrastructure required for online conferencing, however. Stable electricity and reliable internet access are patchy in even the wealthiest countries and near absent in others.

Attending conferences in different time zones also takes a mental and physical toll, which can deprive people of sleep and erode their work-life balance – especially if they have significant caring responsibilities. While pets can be a welcome distraction when they appear on screen, screaming babies, rampaging toddlers or teenagers in search of more bandwidth are not. Generational differences should also be borne in mind; conference organisers have told us that older scholars are less likely to join online than younger ones.

In addition, the inclusivity argument obscures other barriers to conference participation. Being present is not the same as being included. Participation requires training and knowledge of disciplinary etiquette, which is more difficult for newcomers to learn in cyberspace than in person.

Why do we go to conferences? Ever since they became regular events in the 19th century, scholars have questioned their usefulness. Couldn’t research results just be communicated in print? Aren’t the accompanying dinners and excursions, in the words of mid-20th-century chemist Raymond Delaby, just “pretexts for travelling, festivities and mutual congratulations”?

They might be that, but they are much more. Delaby’s contemporary, the anthropologist Margaret Mead, studied conferences as a form of social interaction. She pointed to their miscellaneous overlapping functions, from taking political decisions to formulating a consensus, reporting on new work and stimulating new thinking.

Some of these interactions can be replicated online, but important things happen at in-person conferences that are hard to do without. The most significant encounters are often those over coffee or dinner or while queuing for the loo; that’s when we gossip or share ideas not yet ready for print or even email.

Spending time with people you only know from their publications can lay foundations for new collaborations. Virtual drinks, breakout rooms and private messages get halfway there but lack the spontaneity and freedom of real-life interactions. Nor is it simply a matter of waiting for better software. There are no technological fixes for the complex social phenomenon of the conference. As lawyers arguing against virtual hearings have noted, “expression, atmosphere and manner count for more than we realise, and…are only partly conveyed by remote video”.

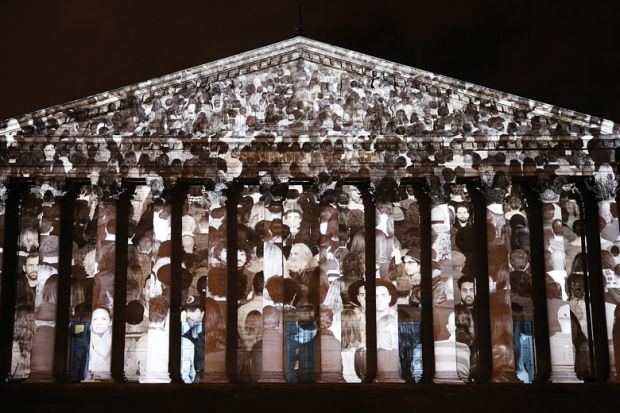

Perhaps most importantly, conferences are reminders that research is not an individual endeavour but a collective undertaking. They build and strengthen communities and professional identities. At their worst, they encourage grandstanding, solidify professional feuds and exclude valid perspectives. But at their best, they integrate new members, honour senior ones, establish relations of trust and identify collective problems and strategies. They are a tool for the communal advancement of knowledge.

By thinking about what we want to achieve at conferences, we can make more deliberate choices about their format. The future will no doubt be hybrid, with online and in-person interactions – possibly at regional hubs – complementing each other. But university leaders and funders need to recognise the essential ongoing roles for in-person conferences in the complex ecosystem of research.

Virtual conferences may be cheaper, but all of us will bear the cost if researchers and their funders are seduced by utopian promises of an online panacea.

Charlotte Bigg is a permanent research fellow at the CNRS Alexandre Koyré Centre. Jessica Reinisch is professor of modern European history at Birkbeck, University of London. Geert Somsen is associate professor in history of science at Maastricht University and the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. Sven Widmalm is a professor in the department of history of science and ideas at Uppsala University. They are investigating scientific conferences from the perspective of social, cultural and political history as part of a project funded by the European network HERA.

后记

Print headline: No amount of technology can replicate the magic of in-person conferences