Australian authorities should pay less attention to the “front end” of the research funding process and take more interest in the finished product, according to a leading scientist.

Queensland University of Technology (QUT) nanotechnologist Christopher Barner-Kowollik said that his adopted country’s “bean counting” approach to research funding made the grant application process far too complex and inflexible.

“For pages [submitted] per A$100,000 [received], we easily hold the world record,” he said. “Yet I’ve submitted multiple final reports that no one’s ever read.

“There’s a tendency to micromanage every little bit of the way and be very soft on accountability.”

He said that the “detailed budget lines” in Australian grant documents specified exactly how much money could be spent on things like staff, travel and consumable materials, while recipients needed to outline the “deliverables” in “ever more specific” ways.

This betrayed the government’s misunderstanding of “how an innovation cycle functions”, he said. Breakthroughs like the laser and mRNA technology had come from researchers with no idea where their efforts would lead. “If you look into the history of great inventions, none has ever been made on a grant with a plan.”

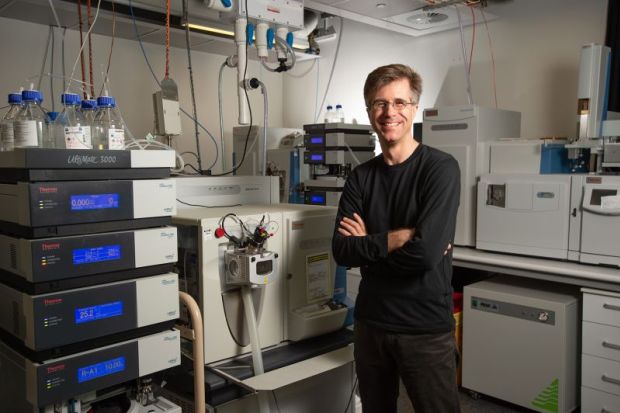

Professor Barner-Kowollik is QUT’s deputy vice-chancellor for research and principal investigator in its Centre for Materials Science. Recently named the winner of this year’s European Polymer Federation Prize, he has also claimed the Australian Academy of Science’s David Craig Medal for chemistry.

He said “milestones” could prove helpful in applied research involving industry partners, but not in basic research. Many of the “most sophisticated overseas agencies”, such as the research council in his native Germany, had “fully moved away from all of this”.

Grant winners were given free rein on how they spent the money, within legal parameters. “Whether you spend it on a postdoctoral researcher or equipment is totally up to you.”

Australian funders, by contrast, were constantly fielding requests from researchers wanting to adjust the amounts that could be spent on consumables or personnel. “It’s a lot of busy work [that] removes the agency from the researchers. A better approach would be to trust researchers, give them flexi-budgets and leave them alone,” he said.

“And when it comes to reporting the outcomes of the research, let them write a meaningful scientific report that is sent out to the reviewers of the original grant. Let the experts determine [whether it] is good scientific progress. The report gets reviewed and the researcher gets actual feedback – and the government or funding agency as well.”

Professor Barner-Kowollik said routine grants from the German Research Foundation came with flexible budgets, while the most prestigious awards did not even require applications or proposals. An example is the €2.5 million (£2.1 million) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, whose recipients are selected on the strength of their career achievements.

Max Planck Society institute directors have to survive a “gruelling” selection process, but are then given “absolute freedom to do whatever they like in research. The past 70 years have led to 37 Nobel prizes with that approach.”

Australia has the wherewithal to realise similar achievements, Professor Barner-Kowollik said. “We’ve got wonderful diversity. We attract people from all over the world. But when it comes to leveraging these strengths and trusting people, we fall short.

“It’s always geared towards the smallest common denominator. It’s like we fear our own courage.”

后记

Print headline: Stop bean counting approach to research funding, urges award winner