When the academic with the self-appointed task of resurrecting Australia’s answer to the dodo bared his research to ridicule from a troupe of stand-up comedians, he decided to land the first blow.

Fronting a small comedy club in one of Melbourne’s quirkier laneways, epigeneticist Andrew Pask related how he had almost let A$5 million (£2.9 million) of research funding slip through his fingers.

“This guy just emailed me out of the blue and said…‘I would like to talk to you about your mission to de-extinct the thylacine,’” the University of Melbourne professor explained. “I ignored the email for two weeks, as you do. I have a lot of crazy people email me all the time. Like, he’s clearly a serial killer. He wants to harvest my kidneys or something.”

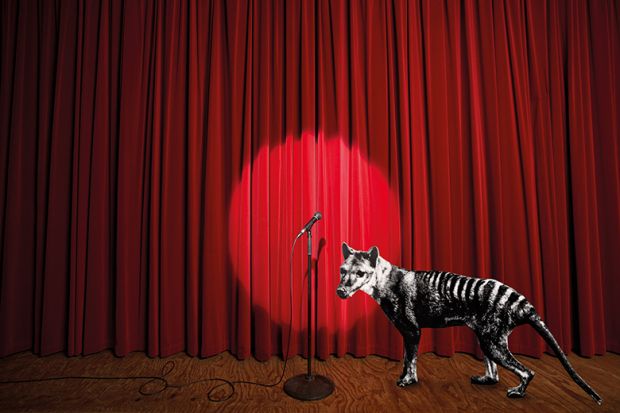

For scientists hankering to bring creatures back from the dead, Australia has plenty to offer. Some 100 endemic species have vanished since European colonisation, including 34 mammals. The holy grail of Australian de-extinction dreams is the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, a dog-like predator that lives on in some people’s memories. The last known specimen died in Hobart Zoo in 1936.

Professor Pask ultimately agreed to a virtual meeting with his emailer. “It was during Covid time, so we were all lonely. I thought, even if he wants to kill me, it might be a nice connection.”

In a subsequent Zoom meeting attended by mysterious business associates, the correspondent revealed himself as a “Bitcoin billionaire” keen to do his bit for biodiversity, and offered A$5 million funding over 10 years to bankroll the thylacine project. “Have I just created this whole fantasy in my mind?” Professor Pask later wondered.

It is not the usual story of tortuous grant applications. And it is not the usual venue for discussions of research funding. The Improv Conspiracy Theatre usually hosts workshops and comedy skits around themes like horror movies and world’s worst jobs.

But every four weeks or so, it stages “The Peer Revue”, where academic research is picked apart by comics. “Each month a different superstar researcher tells stories from their research, which will inspire a cast of talented improvisers to create brand-new, unscripted comedy,” says the show’s blurb. “You’ll laugh, and you also might learn.”

The show is the brainchild of Phillip Dawson, a Deakin University education professor who began moonlighting in improvisational comedy as an escape from the “very serious” world of academia. His research presentations and media interviews have improved as a result, he said.

“Improv is all about listening, first and foremost, and we need more of that. In research, in conferences, in any sort of debate around ideas, we really need deep listening so we can understand other perspectives.”

While researchers instinctively seek weaknesses in each other’s findings – to “shoot other people’s ideas down”, as Professor Dawson puts it – improvisation instead encourages questions such as “yes, and?” and “if this is true, what else is true?”.

“Improv definitely changed the way I am as a researcher,” Professor Dawson said. “I try to explore ideas with people instead of narrowing them down. I’d love it if maybe we tried to ‘yes, and?’ each other a bit more. In my field of education, we’ve had never-ending paradigm wars between qualitative and quantitative researchers that just make us look really silly as a research field.”

He said improvisational humour could also help with the important work of holding research up to robust scrutiny. “Humour can be one way to highlight those potential holes and to show how something is actually pretty funny. Our guests have laughed at those times when we’ve shown how what they do could be viewed as ridiculous.”

Researchers who have volunteered for this sort of treatment include experts in spider crabs, performance-enhancing drugs, koala conservation, the emotional impacts of interior design and religious disputes involving unleavened bread.

The series began with Felice Jacka, director of Deakin’s Food and Mood Centre, who discussed the relationship between gut bacteria and mental health. She was unperturbed by the evening’s scatological turn. “I’m very comfortable with poo and fart jokes – I’m a great fan of them myself,” she said.

“Some of the comedians were very clever. They managed some things that I found hilarious. I think most scientists would really enjoy doing it. It was fun.”

Professor Dawson said the approach brought different crowds together, allowing Friday-night revellers to interact with high-profile scientists such as Professor Jacka – who has featured in Time and The New York Times – and to hear the answers to questions everybody secretly wants to ask. “As the improvisers on stage, we are the buffoon,”Professor Dawson explained. “We are the stupid person able to ask the crazy question.”

The format allows for exploration of “incremental steps” too often glossed over in science news coverage, along with their potential spin-offs. “All of the things that we do along the way are technologies that we need for marsupial conservation right now,” Professor Pask told his audience.

“If ultimately we get to bring a Tassie tiger back, that is amazing. But we can do a lot for marsupial conservation with that basic science.”

后记

Print headline: No joke: academics stand up for research