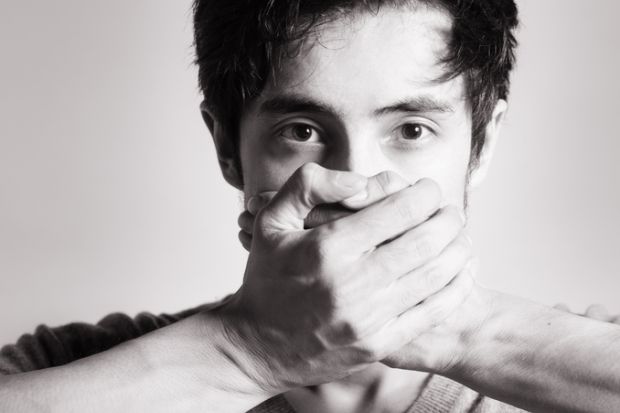

Most US psychology professors self-censor controversial research on “taboo” subjects because they fear sharing it would increase their risk of being fired, a new paper suggests.

In the study, published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, researchers asked nearly 500 psychology academics at leading US universities whether they were worried about sharing a belief likely to be “socially costly”, even if it was backed by robust empirical evidence.

Examples of “taboo conclusions” that respondents were asked to consider included the belief that biological sex is binary for the vast majority of people, that diversity in the workplace did not necessarily lead to better performance, or that men and women have different psychological characteristics because of evolution.

Most respondents were worried about being attacked on social media, being ostracised by academic peers and being stigmatised or labelled in pejorative terms if they put forward a genuinely held, empirically backed belief.

Campus resource: Engaging in controversial topics in teaching and research

A significant proportion also feared disciplinary action, student boycotts, “guilt-by-association harm to students and colleagues” and career-damaging biases against them if they voiced a controversial opinion, even one backed by evidence, the study adds.

“The majority of professors hold empirical beliefs that they perceive to be sufficiently socially unwelcome that it would increase risk of termination if others were to discover those beliefs,” the paper concludes.

Tenure made little difference to whether staff feared repercussions for voicing controversial views, the study also found.

“Tenure does not protect against the most feared consequences among psychology professors – ostracism, social-media attacks, and name calling,” the paper adds.

Lead author Cory Clark, a behavioural scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, told Times Higher Education that she had embarked on the research because “many professors, including many I have never met in person, have confided in me about these concerns” about growing self-censorship in psychology.

“I knew many psychology professors were self-censoring their own empirical beliefs and were quite afraid of social media attacks and peer ostracism,” said Dr Clark.

According to the study, most faculty believe the fact that an empirically sound scientific paper could cause harm to a vulnerable group or even be hijacked by extremists to argue an ideological position is not a good reason to retract a paper.

“To me, these results suggest that a vocal minority of professors – who are broadly and strongly disliked by their peers – have successfully intimidated the majority of professors into silence on these issues,” said Dr Clark.