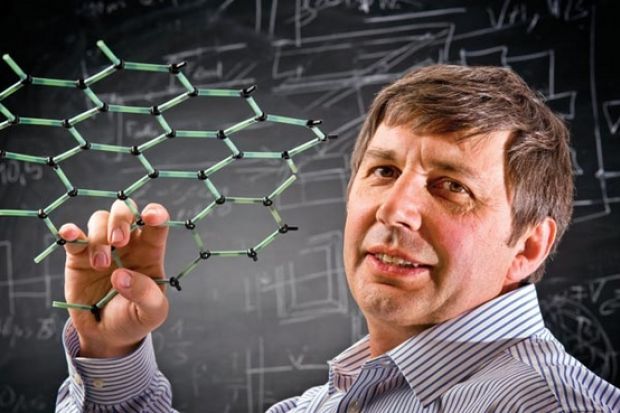

Source: Science Photo Library

Industrial strength applied research should be left to business, says Andre Geim

Forcing academics to carry out applied research is like forcing politicians to design aircraft, according to Nobel laureate Andre Geim.

The professor of physics at the University of Manchester told the Royal Society’s Astellas Innovation Debate last week that applied research should be left to industry, with academics funded to play to their strengths and carry out basic research.

Professor Geim added that he did not believe that requiring academics to address grand challenges, which he likened to “cherry-picking winners”, would lead to the kind of transformative innovation that produces revolutionary technologies.

“Imagine a bunch of chimps sitting in a banana tree pondering about their needs [for the next] 10 or 20 years,” he said at the event in central London on 20 November. “They would improve banana-peeling technology. As a society we are doing the same by investing in [directed programmes] instead of investing in good people.”

Professor Geim described as “peanuts” the £50 million the government is investing in Manchester’s research centre into graphene, the “wonder material” that is the focus of his work and for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics 2010. He said that about £1 billion a year was being spent on research into the material globally.

He was also scathing of the trend for companies to downsize their research and development, and to focus on projects that promised short-term returns. He said typically it took 40 years for a material to move from the lab to the market, and it was too early even to guess what uses graphene may have.

Professor Geim said that many of the world’s largest electronics companies had visited his lab to explore the material’s potential and had left “very happy because no competitor would manage to outsmart them” because of the long timescales he envisaged.

“I can’t find people in big companies to whom I can speak. They don’t understand my language,” he complained, adding that most longer-term research into graphene was being carried out in small start-ups run by his former PhD students.

He also criticised the tendency of many academics to spend their lives researching the same subjects that they addressed in their doctoral work: “We need to break this culture of self-indulgence…when we are talking about curiosity-driven research, it doesn’t mean your own curiosity: it means curiosity for something new as a society.”

The best model for innovation was an interdisciplinary approach to addressing decades-old problems using modern facilities, he added.

“We can ask the same questions but at another level and hopefully find some new answers. That is our competitive edge.”