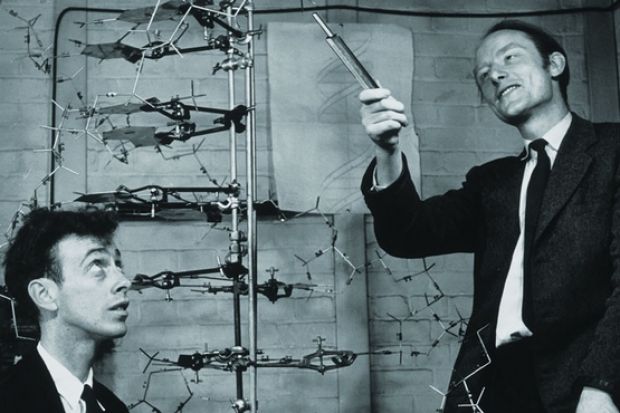

Beautiful minds: Watson (left), Crick and the structure of DNA – just one of the discoveries made at the MRC’s ‘Nobel prize factory’

At the turn of the 20th century, tuberculosis was one of the UK’s worst killers. To investigate the disease, in 1901 the government set up a Royal Commission to answer fundamental questions such as whether TB was the same in humans and animals, and whether cross-infection was possible.

Under the National Insurance Act 1911, the commission was allocated a penny per working person per year to fund TB treatment and for “purposes of research”. No one could have predicted that from this humble national fund – £4 million in today’s money – would spring the Medical Research Council.

As the MRC celebrates its centenary on 20 June, there seems little doubt that the government sees it as a jewel in the UK’s research crown. While other research councils suffered 3 per cent cuts in the 2010 spending review, the MRC received a 5 per cent rise to offset the effects of inflation. In contrast to the modest coffers of 1913, in 2011-12 the council was able to spend £759 million on research and supported 5,700 researchers.

A list of its key achievements over the past century (see timeline below) makes it easy to understand why the MRC seems to have captured both the public’s heart and the government’s wallet, but what underpins those successes? Is it the same body it was in 1913?

Documents show that when it was established as the UK’s first national research council, the MRC had a remit that mirrors its tasks today: to fund institutes, award salaries to “exceptional” researchers and retain the young and talented investigators who would “otherwise tend to drift into other lines”.

Many of the MRC’s most famous discoveries – including the structure of DNA – have been made on one site: the MRC Laboratory of Mo-lecular Biology in Cambridge, sometimes dubbed the “Nobel prize factory” for the nine such awards that have stemmed from its work.

For current director Sir Hugh Pelham, the lab’s success is down to the combination of pressure and freedom that comes with a pure research remit. Without teaching or significant administration duties, “if you don’t do well on your research and you’re failing, you don’t have any other excuse”.

Like other UK research institutes, the lab receives a block grant that allows both flexibility and engagement in long-term projects. As the grant is dependent on the entire lab’s performance there is a community spirit, as it pays for staff to share with and help their neighbours, Sir Hugh added.

Serendipity and flexibility

Of course, the MRC has not backed every major medical breakthrough: Robert Edwards, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2010, was famously denied a grant by the research council in 1971 for his work with gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe on in vitro fertilisation.

But it is only in hindsight that such decisions seem misjudged, argued Tony Peatfield, the MRC’s director of corporate affairs.

“Things could have gone in a very different direction,” he said.

Research is naturally a game of serendipity, and flexibility and independence are two factors that have been key to the MRC’s success.

“The council has always been able to use [its] discretion about what the most effective ways are to deliver that ultimate aim of improving human health,” Dr Peatfield said.

Since the MRC’s inception, the Haldane principle – that scientific decisions should be made at arm’s length from government – has remained vital and has inspired similar set-ups in research councils around the world, he added.

“Ministers always want to do the right thing, but I think if the research councils were formally part of the government there would always be more expectation and pressure, even if subtle, that research would become more short-term and departmental mission-oriented,” he said.

Within the MRC’s budget, funding is split roughly evenly between its units and institutes and competitive grants. While the first two have enabled the council to change direction in response to crises such as the Aids pandemic and do research in fields where universities were weak, its presence within the academy has allowed it to forge links to other disciplines and undergraduate training.

And as university medical research has blossomed, the two sides have moved closer together over the past 20 years, said Dr Peatfield, a trend that has led to a “step change” in the number of MRC units now based in the universities.

The logic is for units, with their multimillion annual budgets and MRC branding, to save infrastructure and administrative costs by being owned and run by universities, gaining access to fresh funding streams and interdisciplinary research by doing so.

The universities of Cambridge, Glasgow, Southampton and Dundee are just some of those to have established MRC units in recent months, a bonus for the universities as it comes ahead of the October deadline for the submission of researchers to next year’s research excellence framework.

MRC funding has also grown more multidisciplinary and collaborative in recent years, with a continuing trend towards bigger, longer-term and more coordinated initiatives such as the UK Biobank, the Francis Crick Institute and the MRC’s network of e-health centres.

Although directed research has always played a part in the council’s history, including, for example, a programme to study influenza in the 1920s, over the years the council has become more strategic, Dr Peatfield said, although this did not have to mean a decline in blue-skies research.

“It’s part of our strategy to sometimes have no strategy,” he added.

Wealth injection

Over the past seven years the MRC has also moved towards more translational and industry-linked research, engagement that was perhaps overdue, Dr Peatfield said.

Being seen as a supporter of UK wealth as well as health is likely to bolster the MRC’s case ahead of the government spending review, to be announced on 26 June.

Speculation about its future has been rife: one proposal, reported by Times Higher Education last month, called for the MRC’s budget to move from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to the Department of Health.

Heavyweights in the medical research world, including Sir Paul Nurse, president of the Royal Society, have warned against the move, saying it would jeopardise the council’s independence and put in “significant danger” its ability to look simultaneously towards the NHS and the research councils in other disciplines.

For Dr Peatfield, if there were one take-home message from the MRC’s first 100 years, it would be that research funding is a long-term game.

“That the MRC has been around for 100 years must say something,” he argued. “It’s not necessarily a rationale for saying it has to be around for the next 100 years, but something must have been going right.”

elizabeth.gibney@tsleducation.com

Impressive Medical record: MRC timeline, 1913-2013

1913

Established as the Medical Research Committee and Advisory Council

1918

Lord Haldane’s report proposes ‘Advisory Councils’ for research

1919

Committee receives Royal Charter and becomes the Medical Research Council

1920s

MRC-funded work on vitamins wins Nobel prize

1930s

Influenza virus in humans isolated

1940s

Randomised controlled trial design pioneered; the first British cohort study begins; Haldane arm’s-length principle enshrined in law

1950s

Structure of DNA unravelled by MRC scientists James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, alongside Rosalind Franklin. Link between smoking and lung cancer one of “direct cause and effect”, special MRC report says

1960s

Clinical trials of radiotherapy treatment for cancer begin

1970s/80s

Discovery that high blood pressure causes heart disease and strokes. Asbestos’ cancer link proved

2000s

First draft of the complete human genome sequence is published