With the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol in June 2020, the growing visibility of black characters in historical dramas from Bridgerton to The Last Kingdom and recent TV documentary series by David Olusoga and Lenny Henry, the profile of what is often called “black British history” has never been higher.

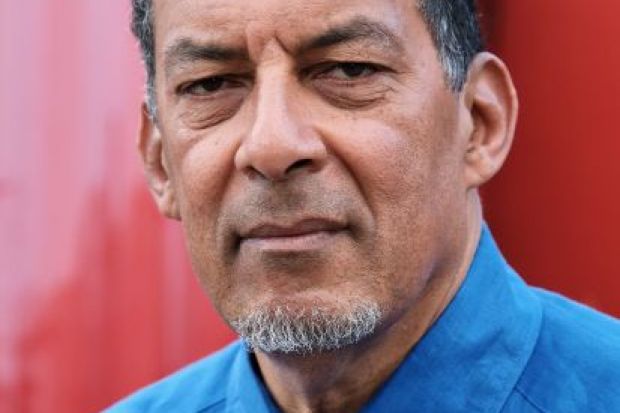

But Hakim Adi, who became the UK’s first black history professor in 2015, is not entirely happy this label has become so popular. “It suggests there is white British history and black British history,” said Professor Adi, now professor of the history of Africa and the African diaspora at the University of Chichester.

“If someone announced they were writing a ‘white British history’ – which, for a long time, is what was studied in universities – I wouldn’t be too pleased. Presenting these histories of Britain as separate things is not helpful,” explained Professor Adi, who himself has nonetheless used the “black British history” tag for books given its name recognition.

His new book African and Caribbean People in Britain: A History, which will be published by Allen Lane in September, aims to tackle this problem of “white” and “black” history, demonstrating how black people lived, worked and prospered on the island for centuries before the Empire Windrush docked on British shores – often seen as the starting point for black history in the UK.

The myth that these individuals held mainly subservient positions in households or were slaves is also addressed; Libyan legionnaires patrolled Hadrian’s Wall, he notes, while Rome’s first “African emperor” Septimus Severus died in York. Two hundred years before Alfred the Great ruled the Anglo-Saxons, a North African scholar named Hadrian was sent by the Pope to England, where he taught and travelled before leading a monastery in Canterbury, he adds.

“A friend visited an exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral and told me there was no mention of Hadrian at all – it is part of this Eurocentric approach to history that takes a lot of effort to change,” reflected Professor Adi, a trailblazer in this field, who, until recently, has been a fairly lonely voice.

Focusing too much on the arrival of the Windrush liner in 1948 – even though it “wasn’t even the first ship from the Caribbean in the post-war period” – risks excluding the stories of millions, he explained.

“We focus on Windrush because Pathé filmed it and [calypso singer] Lord Kitchener sang a nice song but it wasn’t the start – when the passengers got off in Tilbury they were greeted by people from the West Indies,” he noted.

“These weren’t the only people to come in this period too – even if you exclude those from India and Pakistan – there were also a lot of people from Africa who came before 1948; it means millions of people are written out of history,” said Professor Adi.

Correcting this exclusion of African émigrés from British history was a key reason why he become a historian, he said. “I became interested in history at the age of five watching a series about Robin Hood – someone who took from the rich and gave to the poor, which was intriguing. As I began reading history, I realised there was no one who looked like me or my family,” said Professor Adi.

“I began investigating myself, which was very difficult before the internet, and went to university because I wanted to study African history, with the hope of becoming a history teacher,” he continued.

Having been rejected from several teacher training colleges, he took a PhD at SOAS, University of London, and was later appointed lecturer at Middlesex University’s history department in 1995. Getting on in academia was still hard, he reflected. A retired Edinburgh professor, George Shepperson, was the only person who encouraged him and he would only get invited to speak at conferences in the US, Europe or the Caribbean, not the UK.

Through the Young Historians Project he founded, which encourages historians aged 16-25 from black and African heritage, Professor Adi is working hard to ensure more black historians follow him in the academy.

Back in 2014, there were just six black PhD students studying history working in UK universities, noted Professor Adi. “Today I have a dozen PhD candidates studying with me alone,” he said.

The country is now entering a “new era of looking at British history” following the unceremonious removal of Colston by protesters in Bristol two years ago, he continued. “People realise it was unacceptable to have a statue commemorating human traffickers and people who committed crimes against humanity – the powers that be refused to listen to what people said and they felt forced to take matters in their own hands,” he said.

Whether this will translate into a continued growth of black history in UK universities remains unclear, despite several high-profile appointments in recent years, including David Olusoga at the University of Manchester and Olivette Otele at the University of Bristol, to be based at SOAS as of September.

“Many factors have to be aligned if we’re going to see these appointments continue and it’s also important that these academics are getting the right support from their departments too,” said Professor Adi. “But more young people are coming forward to study history – I hope they can get the support that I did not have when I was young."