A “conference and festival” is being held to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the death of radical historian Raphael Samuel.

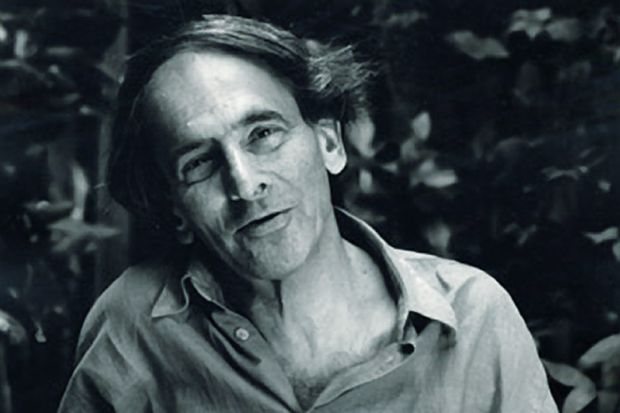

Samuel (1934-96) was the founder of the History Workshop movement, explained Barbara Taylor, professor of humanities at Queen Mary University of London, which “came out of his work with trade union students at Ruskin College” in Oxford.

“He was impatient with the way history was taught at Oxford, where the syllabus included little about working people, so he encouraged students to look into their own industries.”

This led to a series of popular annual workshops at Ruskin, and later elsewhere, which attracted at least as many “students, community historians, teachers, social workers, activists, those working in what are now heritage centres” as it did professional academic historians.

Further links were forged when the first national women’s liberation conference was held at Ruskin in 1970. The highly influential History Workshop Journal was launched by Samuel in 1976.

Towards the end of his life, Samuel moved to the University of East London to set up and run the Centre for East London History, which was renamed the Raphael Samuel History Centre in 2008.

It is now a partnership between UEL; Birkbeck, University of London; Queen Mary; and the Bishopsgate Library. To mark the 20 years since his death and the 40 since the birth of journal, said Professor Taylor, one of the centre’s three directors, they decided to hold their largest event ever “to commemorate Raphael Samuel and the type of history he stood for and did so much to promote”.

“Radical Histories/Histories of Radicalism” will take place, at Queen Mary and other venues, from 30 June to 1 July.

It will open with a discussion of “feminism and radical utopianism”, while plenaries will look at “History Workshop and its legacies” and “radical histories then and now”.

Broad themes include “diversity, difference and beyond”, “local and global histories” and “history, policy, and the idea of politics”. Individual papers will consider everything from “radical squatting” to “coalfield solidarity”, pubs, council estates, domestic labour, Palestinian children’s literature and “anti-racist lesbian thought”. There will also be walks, installations, debates generated by documentary films and performances of radical Yiddish songs.

Although the speakers are likely to be “broadly left of centre”, Professor Taylor said that she “wouldn’t want to guess what perspectives will be presented. I expect some lively debate – what Raphael would call ‘comradely discussion’”, addressing what we can still learn from the History Workshop movement, some of its blind spots and how it can be adapted to the needs of today’s academy and society.

The event, in Professor Taylor’s view, may also stimulate new political thinking, since this depends crucially on “changes in what people imagine is possible”.

“We do feel part of a movement. We are not just backward-looking academics. There has been a real resurgence of feminism, challenges to the neoliberal paradigm students have grown up with which it has been difficult to think past. Young people are very restive about what is happening in education. Dialogue between past and present opens up people to other possibilities.”