In the early 1980s, around the time he was completing a PhD at the University of Kent, Abdulrazak Gurnah spent three years lecturing at Bayero University in Nigeria. He had fled his native Zanzibar to come to England after the 1964 revolution and had never since set foot on African soil.

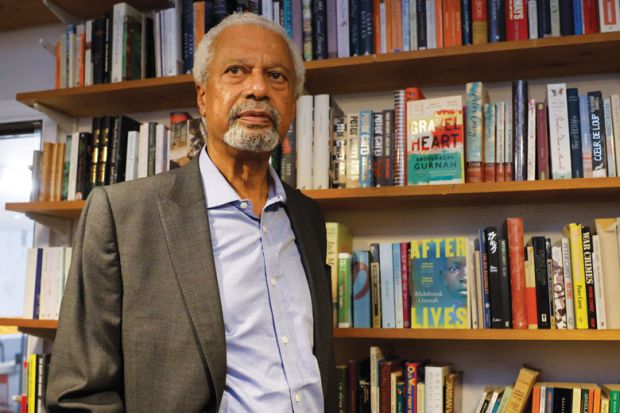

“I had a rather romantic idea of ‘going back to Africa’,” he recalled, “and discovered a different place entirely. Of course I didn’t expect to see another Zanzibar, but I was startled by how different it was from what I had expected.” Challenging and enriching our images of Africa has proved central both to his academic work – he retired from Kent as professor emeritus of English and post-colonial literatures in 2017 – and to the 10 powerful novels that won him this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”. He is due to receive it at a ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December.

So why did Professor Gurnah pursue these dual careers, and how did he keep them going alongside each other?

Even as an undergraduate, he replied, he was both “thinking of doing postgraduate studies and starting to write. Once I had started, I wanted to do both things. At various times, one or the other became the more dominant activity, at least in terms of time, though not in terms of motivation or desire…I was already writing before I became a full-time academic, so I simply accommodated one to the other.” Things broadly became easier as he took on more senior roles as head of department and director of research, since he found that administrative responsibilities were less of a “toll to the mind” than the constant burden of teaching, marking and course preparation.

His research initially focused on African writing, Professor Gurnah went on, because “certain kinds of criticism made me angry, and I wanted to engage with them”. He was particularly wary of “prescriptive or nationalist-minded” approaches that tended to treat literature “like something issued from a platform”. In teaching, too, he was always committed to looking at how every text had “its own integrity and concerns and preoccupations, which you have to bring out for students to see and engage with”.

In graduate studies, Professor Gurnah reflected, “you often start from a position of opposition and want to put things right, and then you see the broader context”. His own later work has moved beyond Africa to the post-colonial literatures of the Caribbean and Pacific, but also to Romanticism and modernism, all linked by what he described as “a whole web of literary and intellectual connections which you can fruitfully study and enjoy”.

In novels such as Paradise (1995) and Afterlives (2020), Professor Gurnah takes us into the largely unfamiliar world of east Africa in the early 20th century, where the few European characters are just ominous presences on the edge. Anyone writing a historical novel set in Victorian London or Weimar Berlin, say, can turn for help to dozens of academic texts. But what sources are available for Tanzanian social history?

Academic material was limited, Professor Gurnah admitted, but he was able to draw on childhood memories of “people in their sixties and so on, who would have been around at the turn of the century and lived through it themselves. My grandfather was a conscript in the German army in the First World War. There were still people alive talking about these things, even if the books weren’t there yet.”

Today, however, in Professor Gurnah’s view, “the scholarship on that period is building up nicely”, with scholars in Africa, the US and the UK, often working in collaboration, now producing “much richer research, using material objects or oral evidence to help us understand more profoundly the cultural practices” of the time and place.

Asked about the arguments for decolonising the curriculum, Professor Gurnah declared them to be “a matter of phrasing”.

Although “the current way of speaking is much more challenging and perhaps aggressive”, he explained, “what people who champion the idea of decolonising the curriculum are after is not much different from what people of my academic generation were trying to do. What is being proposed – including more of the kind of work they champion, making sure that critical positions are not so centred on the supremacy or centrality of British writing – is nothing new…I’m not going to get worked up about what name this process is given. It’s the process I’m interested in – the continuation of the process of broadening what we look at when we talk about literature.”

后记

Print headline: The parallel pursuits of a Nobel mind