"We all sat around talking about men who were sexually harassing and, by chance, the vast majority in the room all named a man who was a terrible predator – he had a bed in his office.”

The occasion, according to Miriam David, a professor at the UCL Institute of Education, was a mid-1970s meeting of female academics from universities across the south west of England, who were discussing forming a women’s network under the auspices of the British Sociology Association. Fearing that the authorities would not believe them, the group decided to warn fellow staff and students about the man by posting a notice in the ladies’ lavatories at the University of Bristol, where both he and David were employed at the time. They reasoned that putting it there was the only solution “because that was a place that men wouldn’t see it”, David recalls.

Meanwhile, in the early 1980s, a group of women on the west coast of the US turned up to a research centre at Stanford University to mourn the death of a colleague. Shelly Rosaldo, an associate professor of anthropology at the institution, had fallen off a cliff and died on a field trip in the Philippines. The impromptu vigil started almost immediately after the news of Rosaldo’s death broke. Myra Strober, who is now emeritus professor at Stanford’s School of Education and was one of the mourners, says that the women knew instinctively where they should meet.

“The entire academic sisterhood came together at the Centre for Research on Women without anybody sending a single message,” she says, adding that she still remembers to this day the feeling of support that she drew from the gathering.

These stories from several decades ago paint a picture of solidarity among female academics, of women looking out for each other in the face of male domination of universities. But what about the modern era? Does anything resembling an academic sisterhood still exist? And should it?

Although discrimination may in many ways be less overt and less conscious, the infamous “leaky pipeline” of female academics suggests that women still run up against both conscious and unconscious barriers to their progression. According to the most recent publicly available figures, for 2014-15, 40 per cent of all academic staff in UK universities are women, but only 23 per cent of professors are female. And of the 136 current UK university leaders listed on Universities UK’s website, only 37 are women. It is a similar story elsewhere in the world. In Australia, for instance, 12 out of 39 university leaders are female, according to the Universities Australia website.

And sexual harassment apparently remains a problem, too. In the wake of the recent revelations about the abuse of women in Hollywood and Westminster (in an echo of David’s story it emerged that a secret WhatsApp group warned female staff in Parliament about male MPs with a history of harassing behaviour), Times Higher Education ran a feature highlighting numerous recent examples of harassment in the academy (“Cultures of denial”, Features, 16 November 2017).

The second wave of feminism, also known as the women’s liberation movement, was in full swing at the time of the discussions about the now-deceased Bristol professor, who had visited David at home shortly after she arrived in the city and chased her through various rooms. David had moved from London, where she had been part of a consciousness-raising group in the late 1960s. “A lot of what we were doing was creating feminist knowledge to use it [for] political, personal and academic change. So it was extremely powerful: we felt very excited by these ideas,” she explains. “We used the concept of sisterhood – [although] whether or not sisters are that supportive of each other is a more contentious question.”

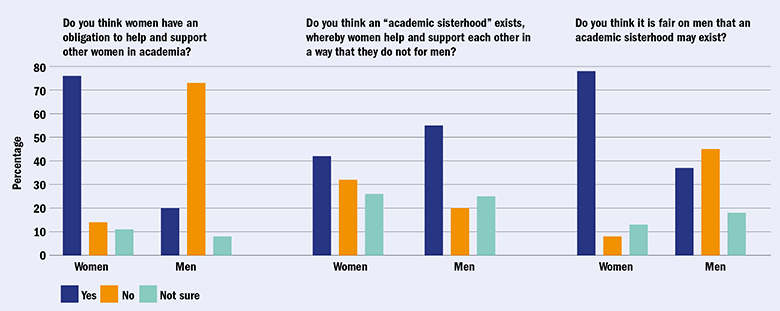

Academics are divided on the question of whether a 21st-century sisterhood exists. An online straw poll of more than 400 academics, conducted in preparation for this article, reveals that 44 per cent of the self-selecting respondents (44 per cent of whom describe themselves as early career academics) believe in the existence of an academic sisterhood, defined as a network whereby female scholars offer each other certain kinds of help and support that they would not offer to men. This compares with 30 per cent who do not believe that a sisterhood exists. Interestingly, women, who make up 86 per cent of survey respondents, are significantly less likely than men to believe that a sisterhood exists: 42 per cent of women have such a belief, compared with 55 per cent of men – although the number of male respondents to the survey is relatively small, so the figures should be treated with caution.

More than half of female respondents (51 per cent) claim to have personally benefited from the help of their academic sisters. Among them, the most common type of benefit is career mentoring and guidance, followed by confidence boosts, support through a difficult situation, and access to networks or influential people in their field. But female solidarity led to tangible career benefits such as promotion or getting a paper published for only a very small number of respondents (just 3 and 1 per cent, respectively, of those who felt that they had benefited from the sisterhood cited such results).

According to a UK-based early career academic in the arts and humanities, in her experience the sisterhood “is no more than personal supportiveness and solidarity among women who know what it is like to be shat on by men. It certainly isn’t some kind of exclusive cabal that is keeping men out of opportunities.”

When asked whether there exist gender-specific networks that benefit men, 69 per cent of all respondents agree, rising to 75 per cent among women (and falling to just 35 per cent among men). For related reasons, 78 per cent of female respondents (and just 37 per cent of male ones) believe that it would not be unfair to men if an academic sisterhood did indeed exist.

“Women are structurally disadvantaged in every aspect of society; why should they not support each other and fight this via a ‘sisterhood’?” asks a female UK early career scholar in the social sciences (social scientists account for 28 per cent of respondents, compared with 42 per cent from the humanities, 16 per cent from medicine and the life sciences and 14 per cent from the physical sciences, engineering and mathematics). “Men’s power has been solidified over centuries in a way that is inherently unfair for women...Men are still free to support each other in whatever way they feel is necessary, but they don’t need to as much.”

Meanwhile, a female academic in the physical sciences, engineering and mathematics believes that “men already benefit from the academic network, which is dominated by men and supports men more than it supports women. We need an academic sisterhood to balance up support – and then we can just have a supportive academic environment for all when we have equal gender representation.”

And while a junior social scientist in Canada is “sceptical” that a sisterhood exists, it “certainly couldn’t outpace the benefits male networks ensure” if it did.

But alongside the supportive tales, those asked about the academic sisterhood also cite stories of female-to-female hostility, bullying and even ideas theft. Of course, these behaviour patterns are also far from unknown among male academics, but there are those who believe that there is something especially reprehensible about a lack of female solidarity. That view was famously articulated by Madeleine Albright, the US’ first female secretary of state and a former Georgetown University academic: first at a 2004 discussion at her alma mater, Wellesley College, and several times subsequently, including during the presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton, another graduate of the women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts. There is, she believes, “a special place in hell for women who don’t help other women”.

The idea that some powerful women in male-dominated fields treat those below them more critically when they are female is nothing new. The phenomenon, known as queen bee syndrome, was coined in the early 1970s by psychologists at the University of Michigan. Popular theories of what motivates such behaviour include the fact that such women have struggled to the top without help and consequently feel that the onus is on others to do the same, almost as a rite of passage. Queen bees might even actively work to keep other women away from the top table, psychologists suggest.

An early career humanities scholar working at a large post-92 institution in the UK, who prefers not to be named, knows only too well how it feels to be the victim of such behaviour. She was left feeling humiliated by the “vitriol” spouted about her by some senior women in her department.

“Online, there’s a fan community, supportive and loving, with a strong sisterly feel. In my institution, however, I have faced some of the most horrendous attacks from older female academics,” she says.

Last year, for instance, she returned to work after a hysterectomy and experienced a backlash from female colleagues, who felt that she was causing them more work and that she was a “whiner”. “One [female] colleague also suggested I was faking the whole thing because I couldn’t hack ‘playing with the big boys’,” she adds, describing the comment as a “punch in the gut: it felt humiliating, as if everything that I’d done in my work with this person was of absolutely no consequence. It was definitely not a sisterly atmosphere.”

A PhD student, who also prefers her identity not to be disclosed, felt betrayed by her female supervisor, who would not fulfil a prior promise to support her application for an extension of her thesis submission deadline after returning from maternity leave. “She dropped me like a hot potato,” says the student, who later found out that the supervisor has been actively working behind the scenes to prevent the university from granting her the extension. Although she has “no idea” of her supervisor’s motive, the doctoral student wonders whether the need for women to “cover their backs all the time” can lead to a “habit of working behind closed doors instead of being transparent”.

Whatever the reason, her experience “made me feel really irrelevant and a failure, and I wanted to give up…I thought that she must be doing this because I am not a worthy scholar.” The incident has also made her more cautious about trusting other academics of either gender: “It is a scar that I will bear for ever,” she says.

Naomi Ellemers, a social psychologist and a distinguished university professor at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, has spent the past 20 years studying the queen bee phenomenon in workplaces, including academia. The mentality, she says, is a consequence of gender inequality, rather than a cause of it: “It is very clearly connected to personal career experiences of individual women.”

Women who have been victims of sexist treatment in academia can react by emphasising how different they are from a stereotypical woman, Ellemers explains. In doing so, they take on traits stereotypically found in men, such as overt ambition, competitiveness and other individualistic tendencies that they feel are highly valued institutionally. But Ellemers is “slowly becoming disaffected” by the term “queen bee” because it implies that there is something inherent to women in the workplace that entails an unwillingness to help each other, or even to tolerate each other’s presence. She prefers the behaviour to be labelled a “self-distancing response”.

“It not something that is dormant in all women,” she adds: it also happens to men from minority groups when they are confronted with stereotypical expectations at work.

Sister act: what survey respondents think about the ‘academic sisterhood’

It seems that even those involved in the original sisterhood movement are not immune from queen bee behaviour. UCL’s David says that some women in her emergent feminist network, who went on to become vice-chancellors and other senior figures in UK universities, became unsympathetic to other women.

“I have never asked them but they may have felt that it was very dangerous to become more supportive of women academics than male academics because it would have been seen as special pleading,” she says.

Susan Bassnett, who became the first female professor in humanities at the University of Warwick in the early 1990s, is “100 per cent opposed” to the queen bee mentality, but knows it exists – in both genders. She was left stunned by the behaviour of two colleagues at one of the women’s lunches that she organised after gaining her professorship. These events brought together a small group of female professors, readers and senior administrators from across the university to discuss their experiences: “All the women who came along thought it was great just to be able to sit and have Chatham House rules and seriously talk” about issues such as pay disparities, promotions and mentoring. But in one session, two “distinguished senior women well known as feminist scholars” flatly refused to do any mentoring. Their motivation, Bassnett recalls, was “more or less that they had better things to do”.

She thinks that such a stance is indefensible. “I think that it is the duty, not just the responsibility, of one generation to help the next. You help them in any way that you can by reading their work if they ask, and helping them to publish,” she says.

Meanwhile, a female professor in the sciences at a research-intensive university in the UK, who asked not to be named, says that in her experience men can be just as bad, if not worse, to each other as women can – but this is much less remarked on: “There is often talk of women in science being bitches to each other, but I have not come across similar talk about men being nasty to other men,” she says.

In THE’s survey, 80 per cent of female respondents report having been treated less favourably because of their gender at some point during their academic careers, but only 22 per cent say that this came at the hands of another woman (57 per cent of men report a similar experience; of those, 65 per cent say that it was perpetrated by a woman). In fact, research suggests that men engage just as often or even more often in the kind of behaviour that typifies a queen bee – such as using malicious humour, excluding people and making them feel inferior.

Although the science professor counts herself as “much nicer” than any of her male bosses, by virtue of being more considerate, offering praise and constructive criticism, and sending Christmas cards to underlings, she has still found herself with a “tough reputation”. She adds that she is often expected to do more nurturing of young talent than her male peers, and that women can be penalised for neglecting these duties in a way that men are not.

“This ‘niceness’ expectation might affect women’s progression to top-level jobs – less time for things that matter for one’s own career,” she says, adding that she feels, from her experience, that “niceness” and leadership may not mix well.

When asked whether women have an obligation to help and support other women in academia, 76 per cent of female respondents (but only 20 per cent of male respondents) agree. In a follow-up question, we asked whether women have a greater obligation to support other women than they do to support men. Although only 45 women responded, the response is interesting: 56 per cent agree that they do, against 29 per cent who disagree.

Countless women’s networks have sprouted up at universities around the world, putting just such an onus on women to support other women. The Women’s Classical Committee UK is one example. Established in 2015, it organises a regular feminism and Classics conference, offers financial support for the costs of travel and childcare for scholarly activities and runs a mentoring scheme for PhD students and early career researchers. One of its co-founders is Victoria Leonard, a research associate at the Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. Until she started a family, Leonard says that she had not noticed the lack of female role models around her because “the issue of gender didn’t always come up. My PhD supervisors were men, my external examiner was a man and my internal examiner was a man. Men have been influential on me.”

Leonard says that older female classicists who she spoke with while founding the committee told her that these networks have always existed informally. “But they are certainly not very visible and they are not easy to join if you don’t know which women are good at giving advice and who could be an informal mentor,” she says. “You can’t always expect solidarity from someone just because they are female – in the same way that you shouldn’t always expect men to be misogynistic and anti-feminist.”

The committee is predominantly for women but it is not gender-exclusive. This is because the goals of diversity and inclusivity are “not necessarily gender-specific and they help and harm people equally”, Leonard explains. Indeed, some academics remain wary of networks that work to further the cause of women exclusively. Dame Athene Donald, master of Churchill College, Cambridge and the University of Cambridge’s former gender equality champion, is one sceptic. She says that while it is tempting for women to want to share experiences with other women, she is “nervous about groupings that explicitly exclude men because women take exception to this in reverse. Social meetings are one thing, but formal structures that are gender-exclusive are another.”

Her point is that genuine progress towards equality relies on both genders working together: “Just because we know the so-called old boys’ network may traditionally have supported men only, that is not a reason to perpetuate a new girls’ network per se…We should shy away from anything that appears to pit half the population against the other half. There may be issues – such as how did you cope with pregnancy – that you really need to discuss with a woman, but general career advice can be offered by anyone with whom you have a good interaction,” Donald says.

Martha Nussbaum, professor of law and ethics at the University of Chicago, finds that she enjoys “an easy rapport with the female faculty that permits me to do things like going to the movies with them, or shopping, that would not be possible for a senior male to do”. But she agrees that “of course everyone ought to mentor untenured faculty”. And when it comes to hiring decisions, the whole department has a responsibility to search for and support female candidates (although not necessarily hiring them if the bar of quality is not passed). “An individual woman should not carry a lone secret crusade but should make her views known and persuade the group,” Nussbaum says.

Indeed, it seems that the hierarchy at Chicago is already persuaded: the institution makes available extra funds for departments that find an outstanding female candidate, according to Nussbaum. Such a thing was unheard of in the early days of Strober’s career at Stanford in the early 1970s – during which, as she vividly portrays in a recently published memoir, she became a feminist after being denied a tenure-track position by her faculty chairman for spurious reasons (“Work in progress”, Features, 9 June 2016). Reflecting on her experience of the sisterhood, Strober says that it has been “utterly sustaining. If you read the literature, men have been helping each other out forever.”

Since she earned her PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1969, she says, discrimination against women has become more subtle – which, in some ways, makes it more difficult to deal with.

“Back then, men would say things that they wouldn’t dare to say now,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean that they are not still thinking and acting on such things.” All the more reason, she adds, to have a sister on your side.

后记

Print headline: Are sisters doing it for themselves?