Look at any nation’s policy aspirations on higher education or research and one word invariably leaps out: excellence. Everyone aims to build it, nurture it, promote it and leverage it. And why not? Who wouldn’t want excellent research, teaching and knowledge transfer?

But while the mantra of excellence might flow easily off the tongue, it is much more difficult to specify what excellence actually amounts to: how broadly it should be defined and how far it can and should be distributed across entire systems – as opposed to being concentrated in a few top institutions.

Concentration is often the preferred strategy, especially when – as it usually is – excellence is defined primarily in terms of research. So-called excellence initiatives are often established in countries seeking to rapidly catch up with more established systems in North America and Europe. These include China’s Double First Class initiative, currently being reformulated for another iteration, Russia’s 5-100 programme, launched in 2013, and India’s Institutions of Eminence programme, set to begin shortly.

There are also examples of developed higher education systems pursuing this approach, as they try to elevate the global status of their top institutions in a world where this can influence academic and student recruitment. Perhaps the most famous is Germany, whose Excellence Strategy is now entering its third iteration. France, too, has sought to amalgamate some of its top institutions into larger units known as ComUEs (communautés d’universités et établissements), in an attempt to boost their collective power and global prominence.

Arguably, excellence initiatives also exist unofficially in other systems whose funding schemes concentrate resources on institutions deemed the highest quality. A prominent example is the UK, whose £1.3 billion-a-year “quality-related” research block grants are distributed on the basis of the inevitably named research excellence framework (REF).

But does this promotion of “excellence” – by whatever mechanism – help to raise the performance of whole systems? That is, does a rising tide in elite institutions raise all boats? Or does it leave some universities and regions drained and marooned? And if it is the latter, is there a better way to approach higher education capacity-building – particularly in the wake of a global pandemic that has only further underlined how crucial universities are to human well-being?

One question is whether declared excellence strategies are effective even on their own terms. The answer appears to be a cautious “yes”, particularly in relation to research metrics and global ranking positions.

“When you look at those countries that have made a lot of progress, most of them would be countries that have an excellence initiative,” says Jamil Salmi, a former tertiary education coordinator for the World Bank who has been analysing the efficacy of such strategies for a number for years. However, Salmi’s analysis is based on one particular measure: performance in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (formerly known as the Shanghai ranking), relative to size of national populations.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford and director of the Centre for Global Higher Education, says that while the quality and quantity of research produced are possibly the most obvious indicators of excellence, there are other measures that can capture its wider effects. These include the number of students graduating with doctorates by field; changes in patterns of research collaboration locally, nationally and internationally; and the flow of people in and out of universities in the country. Another factor is “industry, social and governmental take-up of research”, although Marginson notes that this “is not so directly driven by an excellence programme, and depends on other conditions”.

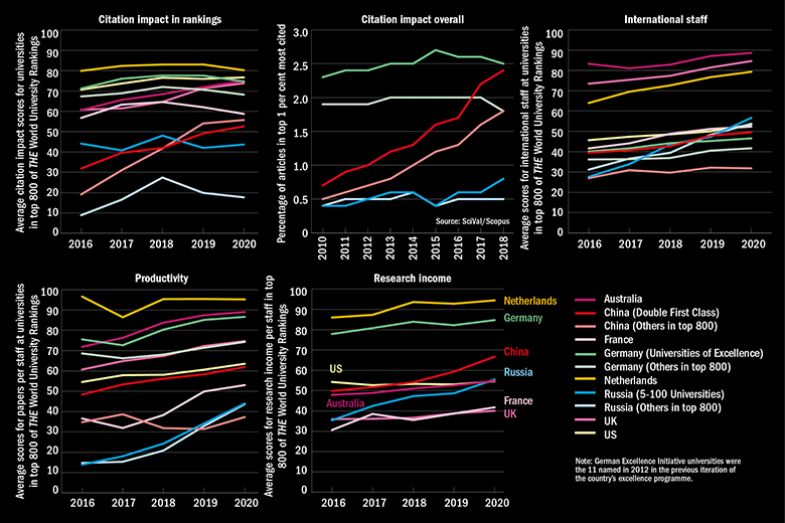

It is possible to examine some of these factors using data from Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings. Such an approach is inevitably limited by the fact that the rankings only feature the world’s top tier of research universities, but since this is the level at which excellence initiatives aim, it does cover many of their members.

Analysis of average scores for institutions that have appeared in the top 800 over the past five years suggests that some countries with flagship excellence initiatives have seen relative improvement on at least some measures. For instance, research productivity and internationalisation of staff bodies have increased in Russia, where about 20 universities have been part of the Project 5-100 strategy.

However, it is important to note that some strategies have been explicitly focused on the various metrics that feed into rankings. For instance, a key process among 5-100 universities is to move research activity – a big focus of rankings – inside higher education institutions that, in the past, were more focused on teaching (France’s ComUE programme also brings various formerly independent research institutes under university umbrellas). The natural result is a rise in publication quantity in 5-100 institutions – although the initiative’s initial goal to propel five of them into the world’s top 100 by 2020 is still far from being achieved; the only Russian university in the top 200 in THE’s 2020 rankings, Lomonosov Moscow State University, is joint 189th.

James Wilsdon, professor of research policy at the University of Sheffield and director of the Research on Research Institute, cautions that while “it is an entirely legitimate aspiration for governments to want to improve performance in their systems”, it is crucial to ask which “criteria are being valorised and counted and rewarded in that process” – although undeclared initiatives such as the REF can also introduce similar distortions.

Narrow definitions of excellence inevitably “deprioritise and gradually pull support and resource away from other sorts of activity,” Wilsdon adds. “The question is what is it about that other activity that might be quite precious and that you might want to preserve.”

Moreover, setting certain goals potentially risks unintended consequences. For instance, setting quantitative goals may introduce incentives to churn out poor-quality scholarship, while focusing on research quality metrics, as China’s Double First Class initiative does, risks incentivising research misconduct.

Xin Xu, a postdoctoral research fellow at Oxford’s Centre for Global Higher Education, believes that there are signs of the Chinese government trying to change tack as it devises the terms of the latest iteration of the Double First Class initiative: “Research evaluation is moving away from largely relying on publication numbers, impact factors or [publication in certain] journals, to highlighting peer reviews and the quality and contribution of the research itself,” she says.

There is also the issue of whether concentrating funding on an elite, however defined, opens up unacceptable performance gaps between those universities and the rest of the system. Separating out those institutions in the World University Rankings that are part of a country’s designated excellence strategy from those that are not does suggest that sometimes members of the initiative have improved more quickly.

However, this is not always the case. In China, for instance, the system as a whole seems to be on a rapid upward trajectory. Indeed, average citation impact scores for “other” top 800 Chinese universities in the rankings has overtaken that of Double First Class participants – although citation data from Elsevier’s Scopus database suggest that proportions of research in the global top 1 per cent have improved more quickly for Double First Class institutions.

It is also worth noting that similar improvements – or, at the very least, maintenance of high standards – are evident in countries that do not have declared excellence programmes.

But even if members of excellence initiatives do not conspicuously outperform non-members or institutions from countries that lack such initiatives, it is arguable that this should not be taken as a failure of the initiative. Advocates of the Double First Class initiative, for instance, may see China’s general improvement as a welcome and intended spillover from the increasing international prominence of institutions such as Peking and Tsinghua universities, boosting the reputation of Chinese science and drawing more top researchers to the country.

Excellent initiatives: What the numbers say

A nation with particular concerns about the potentially regressive effects of designating elite institutions is Germany. Some observers worry that its Excellence Strategy – originally launched in 2005 as the Excellence Initiative – is eroding what they regard as one of its great strengths: its egalitarian model of higher education.

The latest iteration of the programme, announced last year, awarded 10 universities and one consortium of institutions the status of “universities of excellence”, while a separate “clusters of excellence” stream provides project-based support for research areas that can involve several institutions.

Although the amount of money involved is relatively modest by comparison with some other schemes – a total of almost €400 million (£350 million) a year for the clusters and about €150 million for the institutions – critics still think that elevating a group of universities over others creates the potential for problems. Michael Hartmann, emeritus professor of elite and organisational sociology at the Technical University of Darmstadt, says that the “great danger is that the German university system will be profoundly divided”, with the “winners in the competition for excellence…permanently separated from the losers, both materially and symbolically”.

He says that in addition to the direct funding they are awarded, universities of excellence also attract a growing proportion of grants from the German Research Foundation. But the symbolic effect of the excellence designation is “even more important”, he believes: “There are now two classes of universities. In the long run, this will also change the social recruitment of students. Following the pattern of other large industrialised countries, such as the UK, France, Japan or the US, they will increasingly prefer universities of excellence.” This, he says, will “promote the homogenisation” of Germany’s social and economic elites.

However, Inka Sprang-Grau, who heads the excellence strategy unit for one of the two organisations running the programme, the German Council of Science and Humanities (Wissenschaftsrat), says that the country’s experience of running such a programme since 2005 means it has thought carefully about diverse definitions of excellence and how the whole system can benefit.

“The programmes were designed in light of the specific history, structure and broader development needs of the system of higher education in Germany,” she says. They embrace a “multidimensional and comprehensive definition of excellence” that factors in the “interplay between excellent research, teaching and knowledge transfer, as well as other aspects, such as supporting early career researchers, diversity and internationalisation”.

Moreover, while the initiatives can’t solve all the challenges faced by German universities, it is still an “overarching goal that the programme should leverage the potential” of the entire system. Specifically, Sprang-Grau says that other universities gain from the strategy directly, “by cooperating with researchers from the funded universities”, and indirectly, by, for example, “learning from the strategies of the most successful universities in the field”.

Sprang-Grau accepts that the question about elitism posed by scholars such as Hartmann “always remains one of the central challenges for any excellence programme” and is “still a cause for debates in Germany”. But she points to the programme’s periodic reviews and the fact that the clusters stream can involve more than just the universities of excellence (although Hartmann counters that they are still “concentrated predominantly” on such institutions).

In Marginson’s view, German policymakers understand “better than most” that if an excellence programme is about building national research capacity, it must factor in ways to ensure that “everyone is lifted”.

Wilsdon also points to Germany’s federal system of government as potentially helping to underpin such considerations, something that has arguably been missing from the UK’s approach to research funding. Although the REF’s “place-blind” nature has sometimes “been seen as a strength of the system”, it has led to regional concentration, Wilsdon observes.

“Then you get to the point we’re at now when suddenly you are saying: ‘Hang on…is that exacerbating all sorts of other socio-economic tensions in the country?’” Hence the current UK government’s focus on “levelling up” research funding and other factors in less prosperous regions.

Wilsdon notes the irony that Germany’s excellence strategy appears to be coming from the opposite direction in wanting to build the kinds of “peaks of excellence” that the REF enables.

Concerns about the regional effects of excellence programmes also exist in China, but Xu says that Double First Class seems to be making a greater effort to address these issues than did its predecessors, the 985 and 211 programmes, both launched in the 1990s. “For instance, it has included…universities from Xinjiang, Yunnan and Henan provinces, where there were no 985 universities,” she points out.

Another major risk of defining excellence narrowly is that it can create a tier of universities that become less innovative and overly focused on certain disciplines and fields – especially those seen as global priorities, such as artificial intelligence, where grants are easy to come by. Marginson warns that this can mean “lots of dross work” being produced at these institutions. “It is usually the unfashionable and half-glimpsed issues that are the real cutting edge,” he says.

Even in a diverse higher education system such as that of the US, there can be pressure to switch from conducting research with “local relevance and usefulness towards a single concept of ‘excellence’”, according to Caroline Wagner, Milton and Roslyn Wolf chair in international affairs at Ohio State University.

“Excellence programmes stifle variety and force what academics call mimetic isomorphism,” she explains: institutions mimicking each other because they believe that this is the path to success. “The most lauded [institutions] become less innovative over time – they must retain their reputation”, but “the best new ideas will come as a result of variety and true exploration by those willing to take a risk.”

Such considerations are “crucial” in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, Wagner adds. “Holding on high the medal of ‘excellence’ actually works against what we are trying to accomplish with Covid-19 research,” she warns. “The answer is likely to come from an unlikely place.”

Ellen Hazelkorn, founding partner of BH Associates education consultants and professor emeritus in higher education policy at Technological University Dublin, agrees that a key lesson of the pandemic is the “importance of multilateralism” in research because “no country, no centre has the capacity – or the resources, or the infrastructure, or the talent – on its own to resolve what are increasingly global problems.” Hence, concentrating funding on a small number of institutions would put a nation at a “huge disadvantage”.

A broad range of well-funded institutions is also important in terms of building human capital, Hazelkorn adds. “At the end of the day, the biggest outcomes of our universities are people,” she says. “And what we are now going to have is a huge responsibility for skilling, re-skilling and re-educating” to help economies recover from the pandemic.

Salmi too, points out that one of the biggest dangers from the focus on excellence relates not to research but to the effect on the wider system of higher education.

“If we keep pushing this notion of excellence and we equate excellence with top research universities then I think that is very dangerous,” he warns. “For me, you can have excellence in a community college and excellence in a Fachhochschule (University of Applied Science) in Germany that play a very important role.”

So where does all this leave excellence strategies? If, by their very construction, they are diverting resources and attention to one aspect of higher education, would it be better for policymakers to be more comprehensive in their strategies?

Cameron Neylon, a professor of research communication at Curtin University in Australia, co-authored a paper in 2017 that questioned the whole premise of a focus on “excellence” in academia. For him, it is difficult to point to any country that has defined excellence in such a way that it does not create distortions in the system as a whole.

“There are some countries that do a less bad job of this, but that is primarily due to their having more resources to spread around – so there tends to be a higher diversity of activities – or because the institutions are relatively wealthy and can support a wider range of ‘unfunded’ research work,” he says.

He points to nations such as Germany, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands, as well as funders such as the International Development Research Center of Canada, which are “focused as much on developing capacity and skills as they are on research outputs”.

But Neylon accepts that building national research capacity without resorting to some sort of concentration is a “wicked problem” since “with limited resources, choices need to be made. And, ideally, those choices would be as objective as they can be, supporting those efforts that will lead to most benefit,” he says.

The issue is that “there are no objective measures, and those that look the most ‘reliable’ because they are quantitative [such as citation metrics] are actually among the most biased and least useful, particularly in the context of low- and middle-income countries and regions”.

In Neylon’s view, one way to make progress when resources are limited is for prestigious institutions “to support and build capacity” elsewhere in the system, and then try to assess the effectiveness of such efforts.

Such “hub and spoke” approaches have often been mooted, but are arguably much easier to implement where regional governance structures are prominent, as in federal republics such as Germany and the US.

For Salmi, it is also important to consider other issues around governance and the wider structures that universities operate under, relating to issues such as their autonomy and legal status. “That is one of the limitations of the excellence initiatives in Russia, France and Germany,” he says. “If they don’t significantly alter the governance framework and give more flexibility [to university leaders] then that undermines the [additional] financial contribution.”

Perhaps, though, when all is said and done, the sheer amount of money that is invested in a research system is more important than the details of how it is distributed – especially in countries that are trying to “catch up”. Data from the World University Rankings illustrate this: across all Chinese universities in the top 800, the average score for research income per staff member has moved well ahead of some other major research nations in recent years.

China’s rise could be thought to raise particularly pressing questions for the US – which, owing to its status as the world’s research powerhouse, has never seen the need for any kind of national excellence programme.

For Salmi, the current Covid-19 crisis may accelerate scrutiny of how resources are allocated in US higher education – which has already seen the funding gap between top private institutions and state universities grow since the 2009 financial crash.

“The US has this paradoxical feature,” says Salmi. “Yes, it still has the top universities in the world, but, as a system, I am not sure it is top – and certainly it has many elements of dysfunction.”