New Times Higher Education data suggest that universities are not walking the talk on interdisciplinary science, with about a third of participating global universities failing to reward staff for cross-disciplinary research or to measure the success of such work.

Interdisciplinary research is often lauded as fundamental to solving the world’s most pressing problems, by university leaders, politicians and funders alike, and many higher education institutions have buildings, facilities and staff focused entirely on drawing insights from a range of scholarly fields. But recognition and reward for such work is less common.

More than 700 universities across 100 countries/regions submitted qualitative data to THE on several measures relating to interdisciplinarity, and the vast majority of those institutions said they provide specific physical facilities (92 per cent) and specific administrative support (86 per cent) for interdisciplinary teams.

However, lower shares of institutions said they have measures of interdisciplinary success (70 per cent) or a tenure or promotion system in place that recognises interdisciplinary research (62 per cent). And of those that answered “yes” to last two questions, just 12 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively, provided specific evidence to show that those processes were in place.

The data, which relate only to interdisciplinary research in science subjects, was collected for a preliminary analysis conducted in association with Schmidt Science Fellows. The aim is to develop a new ranking measuring universities’ contribution to interdisciplinary science.

Of the 629 institutions that submitted quantitative data, 85 per cent provided figures on their recruitment of interdisciplinary researchers, while 83 per cent supplied information on the proportion of research funding dedicated to interdisciplinary research. Asia accounted for the highest share of responding institutions, led by India, with 55 submissions.

On average, across all responding institutions, there were 0.07 job adverts for interdisciplinary science researchers per academic staff member in the 2021 academic year. However, there was wide variation by country: this figure was as high as 0.14 ads per staff member for Iraq (when analysing countries with at least 10 valid submissions), while Japan’s 27 responding institutions reported having no adverts for interdisciplinary science researchers.

Meanwhile, Egypt has the highest share of interdisciplinary research income – 48 per cent – while Brazil is bottom on this measure (3 per cent). The global average based on submissions is 28 per cent.

Duncan Ross, THE’s chief data officer, said “for universities to address interdisciplinary science research, far more importance needs to be placed on evidencing what they are doing”, particularly in “recruitment and recognition of interdisciplinarity”.

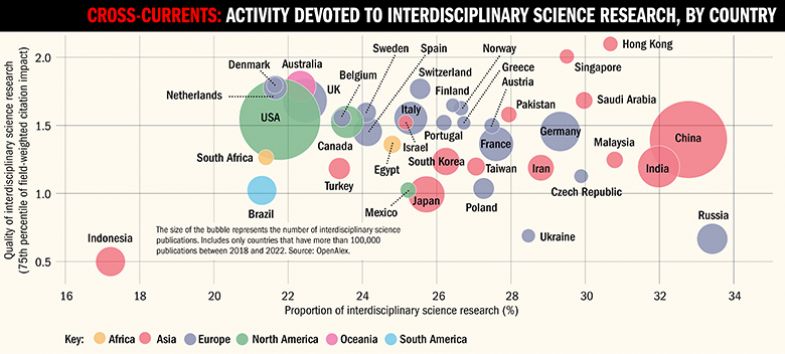

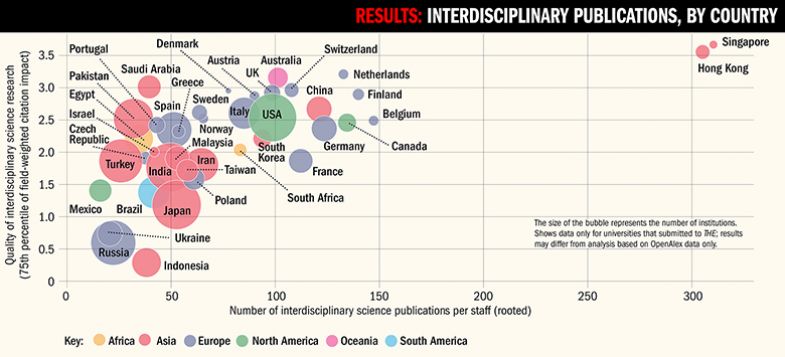

The research also analysed bibliometric data from OpenAlex to assess the quantity and quality of interdisciplinary publications in different countries.

The figures show that the world’s traditional research hubs – such as the US, the UK and Australia – are much less focused on interdisciplinary research than the main higher education systems in Asia.

Overall, China leads the world on both the overall volume and percentage of interdisciplinary research. The country published more than 1 million cross-disciplinary science papers between 2018 and 2022 – representing 33 per cent of its total scientific research output.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong and Singapore come out top when judged on the quality of interdisciplinary research, based on the 75th percentile of field-weighted citation impact.

The US is second on volume of interdisciplinary research, with almost 800,000 cross-disciplinary publications, but this accounts for less than 22 per cent of its scientific output.

One might assume that the leading Western nations have proportionally less interdisciplinary research because they are more focused on single-discipline fundamental research. This explains some of the gap in performance, but the US, the UK and Australia still trail China, Hong Kong and Singapore based on the volume of interdisciplinary publications per staff. South Korea is also fast catching up with those three English-speaking nations.

Rick Szostak, an economics professor at Canada’s University of Alberta and author of the book Integrating the Human Sciences, said the world’s top-ranked universities “may give lip service to interdisciplinarity but still prioritise publications in disciplinary journals”, while university administrators do not necessarily have “a very good idea about how best to support this” work.

“Countries that are developing their university systems later than happened in Europe and North America may recognise an opportunity to stress interdisciplinary research, and are better able to pursue this if disciplines are not yet entrenched in positions of power,” said Professor Szostak, who was formerly president of the US-based Association for Interdisciplinary Studies (AIS).

Machiel Keestra, assistant professor in the Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies at the University of Amsterdam and also a past president of AIS, said the variations between countries also reflected how science was organised in different contexts. China was “much more top-down oriented”, and its government had promoted interdisciplinary centres, he said.

On the relatively low share of universities rewarding interdisciplinary research, Dr Keestra said “even though interdisciplinarity is increasingly being promoted, the infrastructure and environment is still not up to the task in many ways”.

“Everything is still very much disciplinarily organised” in universities and journals, he said.

“Many institutions will have [interdisciplinary] education or research programmes, but they are often subsumed under one or the other department. In the case of budget crises, these centres or programmes tend to be vulnerable because people want to keep first their disciplinary orientation and programmes.”

Dr Keestra added that universities and journals tended to have promotion or publication criteria that could be generally applied across disciplines, without taking into account the unique characteristics of interdisciplinary research. For example, it generally takes longer for interdisciplinary research to both lead to publication and to gain citations.

Professor Szostak said he hoped that the research from THE and Schmidt Science Fellows “encourages universities around the world to revisit their approach to interdisciplinarity”.

“Ensuring appropriate career progress decisions is a first step they can take. Creating truly interdisciplinary teaching programmes – that teach students how to integrate insights from different disciplines – will then create faculty positions for interdisciplinary researchers. These programmes also need to be evaluated – and budgeted – fairly,” he said.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com