If, in 2013, there was anything anywhere in higher education more hyped than massive open online courses, I missed it

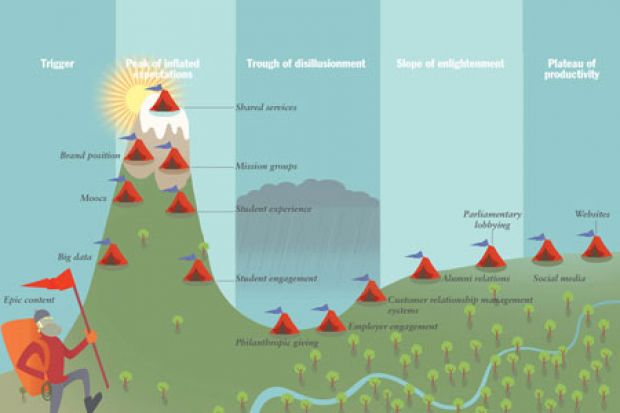

A high-powered group of marketing and communications directors visited the University of Greenwich recently. In my welcome talk, I introduced this forward-thinking bunch to a device called the “hype cycle”. Originally developed by the IT research consultancy Gartner to describe emerging technologies, I thought it would stimulate debate if I applied it to university marketing communications.

The classic hype cycle follows new ideas or technologies as they track though five development phases: initial trigger; “the peak of inflated expectations” when things are talked up as the latest and greatest; “the trough of disillusionment” when commentators seek to bring them back down to earth; “the slope of enlightenment” when people begin to find out that new things are good in some ways but less useful in others; and finally “the plateau of productivity” when realism sets in and people see how things can actually be applied in a useful way.

I began by discussing some of the ideas being billed as “the next big thing”, such as the marketing concept “epic content” – the importance of focusing on content that prospective clients really want to engage with. Another is “big data”: the idea that complex datasets generated from, for example, social media analysis, can be used to profile and target groups more effectively. Will big data get bigger in 2014?

Then I moved up the curve. If in 2013 there was anything anywhere in higher education more hyped than massive open online courses, I missed it. Moocs are, we are told, a disruptive technology that will change universities for ever and will send some to the wall. Sadly, I still think that more hype will be piled on top of the already very large mound and the Mooc balloon is still going up. In 2013 more was written about Moocs than is actually known. Watch out for the naysayers in 2014.

Right at the top of the peak of inflated expectations is the concept of “shared services”. The idea that universities can radically reduce the cost of business by simply sharing between them services such as payroll, IT, security and catering is much oversold. If it is so obvious and the savings so great, why hasn’t it been done already? Or have all the easy wins already been achieved?

For me, two ideas that are sliding down from their inflated peak are the concepts of “the student experience” and “student engagement”. For some time, we have been exposed to the mantra that students have new rights and expectations as consumers, and that we must engage with them at every opportunity because co-production of knowledge is central to learning. There is also an arms race under way, as universities try to build the biggest and best student housing, climbing wall or swimming pool to entice new “customers”. But has anyone tried to get students involved in quality enhancement these days, or asked them how important vanity buildings are to their choice of institution?

Bang at the bottom of the trough of disillusionment, I place philanthropic giving. A few years back, many universities invested to take advantage of the government’s matched funding scheme: development staff were hired, giving campaigns spun up and worldwide alumni contacted. Outside a small group of old universities, however, vice-chancellors are now wondering: “Where’s the real return on investment?” But, I contend, fundraising is set to climb the slope of enlightenment. Realists are beginning to see that this is a long game and that many of its benefits are not financial in nature, such as mentoring, internships, advisory board memberships and guest lectures.

One much-hyped government initiative of recent times is employer engagement. “It’s easy to solve the funding crisis in higher education – we’ll just get employers to pay” the logic goes. Employers take a different view. They see universities simply as an extension of their training departments and want a production line of “work-ready” graduates. CBI members in particular have been quick to draw alleged shortcomings to the attention of government ministers, the right-wing press and anyone else who will listen. Are we at last beginning to see that employers are, by and large, hard-nosed and that in a recession they don’t have to try too hard to recruit good employees?

Also rising from the depths of the cycle trough are customer relationship management systems which have been grossly over-hyped for many years now, often by marketing departments wanting their own toys. Populating the databases, connecting the systems to the rest of the IT enterprise and integrating with business processes was a challenge. But to my mind, at that stage CRMs were talked down too far and now we can evaluate them more dispassionately, seeing them as useful marketing and student recruitment tools.

Then there is parliamentary lobbying, a topic much loved by mission groups and the biggest mission group of them all, Universities UK. Do parliamentarians really take notice of academics? How high on their list of vote winners/losers is higher education? Would we be better keeping our heads down and spending our money on academic staff instead of endless meetings with policy wonks? Or should we divert a larger proportion of UUK subscriptions into the “wining and dining MPs fund”? Lobbying seems to have emerged from the bottom of the hype cycle as we now recognise both its limitations and its ongoing value.

I sometimes wonder what is fuelling this hype cycle. Is it government pressure, consultants who want to offer their services, thought leaders who want to create an agenda, an overactive media? Or perhaps it is just a natural consequence of the diffusion of innovative ideas. Whatever the answer, universities should be first to cut through the hype.