Sometimes the obstacles to research can prove unexpectedly illuminating.

In our occasional Outer Limits series celebrating academics who have gone “outside the comfort zone”, we have profiled a number of bold and inspiring figures who have brought back important insights by venturing into tribal war zones, working among child labourers in remote Himalayan villages or even putting tags on sharks and other fierce creatures.

Yet some equally promising projects fall foul of universities’ and insurance companies’ security concerns, not to mention the objections of researchers’ families. There are times, however, when this proves a blessing in disguise…

Take the case of Ruben Andersson, associate professor of migration and development at the University of Oxford, who I profile in a feature article this week. Long an intrepid traveller, he had hoped to research undocumented African migrants to Europe by crossing the Sahara with some of them. When this proved impossible, he carried out his investigations in North Africa and Spain and interviewed potential migrants in Dakar, the capital of Senegal.

What he soon discovered was that he was part of a minor industry of academics, journalists, policy makers and NGOs all keen to interview, understand and control the very same people. It was this central insight that formed the basis for Andersson’s first book, Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe. He may not have learned first hand about often terrifying migrant journeys, but he was able to illuminate instead what he calls “the early stage of the border control industry”, which was soon to be ramped up at the time of the 2015 refugee crisis.

Something similar happened during Andersson’s work on his new book, No Go World: How Fear Is Redrawing Our Maps and Infecting Our Politics. He was keen to visit places in Mali such as the military training camp in Koulikoro. But his then employers, the London School of Economics, sunk this plan when they put him in touch with a security company which told him that he would have to pay an extra £1,000 in insurance premiums if he left the capital, Bamako.

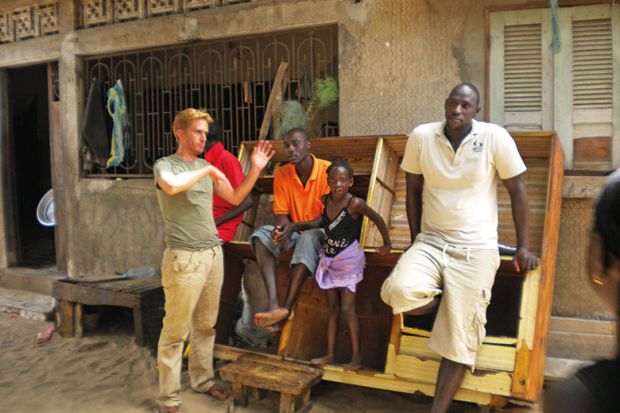

So Bamako, disappointingly, it was. Yet hanging out there soon made Andersson realise that he was far from alone. Many Western governments were involved in peacekeeping and humanitarian operations in Mali (often with the more or less overt goal of clamping down on the perceived dangers of migration, smuggling and terrorism). Yet most of their staff were stuck behind bunkers in Bamako and engaging with the war-torn parts of the country only at a distance.

The reality and futility of such hands-off involvement provides the sobering theme for No Go World. What a very different book it would have been if Andersson’s initial research proposal had been accepted unchanged.

Matthew Reisz is a reporter for Times Higher Education.