Over the past few years, I’ve had a couple of conversations with friends that left me wondering exactly what universities have become.

These friends are either in the middle of a PhD or contemplating doing one, and inevitably we turned to discuss whether a career in academia would be worthwhile. They wanted, simply put, a life that gave them time to think deeply about their chosen subject.

This is still, on the whole, what we think should be the essence of academia. Universities are supposed to provide space for serious thought. But I came away from our chats wondering whether my friends might have better luck pursing this goal outside the academy (more on this later).

These conversations came to mind last week when I discovered a rare treasure trove of data about how researchers in the Netherlands spend their time.

What emerges is a disheartening picture of professors who have little time for research (despite promises to the contrary from management) and work scarily long hours.

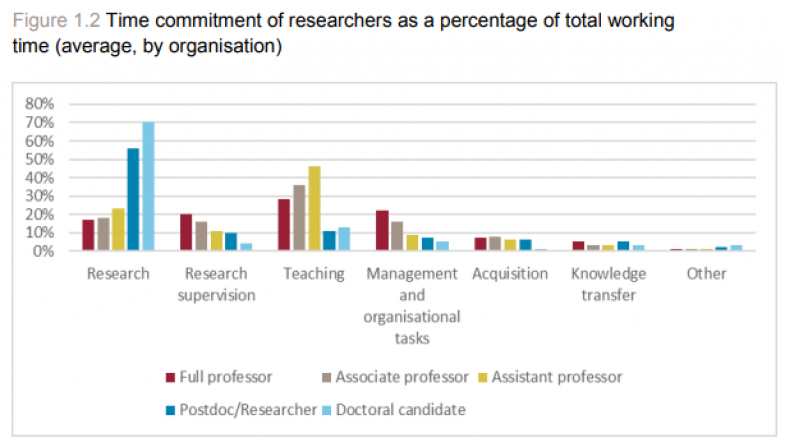

Those lucky enough to have become full professors – supposedly the light at the end of the tunnel for struggling junior scholars – spend just 17 per cent of their time on their own research. Teaching, research supervision and “management and organisational tasks” were all bigger commitments. Associate and assistant professors fare little better carving out research time for themselves.

This is not what many signed up for. Nearly half of university researchers complained that they had ended up doing less research than agreed (women got a particularly raw deal in this respect). But as the survey results also revealed, doing good research is by some distance still the main reason academics get out of bed in the morning.

These figures may come as no surprise to many readers. But it’s worth stepping back and sighing at what it all means: progression in academia is often progression away from why you got into it in the first place.

Overwork is also brutally common. On average, full professors work 45 per cent longer than their contracted hours – assuming a 38-hour contract, as the report does, that means a 55-hour working week, or an 11-hour working day. Those at the assistant and associate professor level put in an extra 29 per cent on top of their contracted hours.

Let’s run the numbers on these. If the average full professor is working a 55-hour week, and spends 17 per cent of their time on research, they get about 9 hours 20 minutes a week to pursue their own research interests.

Now, as I asked my friends, if you worked part-time to pay the bills, and fitted your research around that, how much time would that give you?

Working a 55-hour week like a full professor, and doing a four-day, 30-hour a week job to keep the wolf from the door, you’d be left with about 25 hours a week of research time. That’s starkly more.

There are obvious caveats. If your research requires, say, a million-pound microscope, you’ll unavoidably need an institutional position. If you like teaching, then the trade-off isn’t nearly as worth it. Keeping up your research commitment is bound to be harder when not physically surrounded by students and colleagues – scholarship is collective, after all. Library and journal access could be tricky. And credentialing is also a problem – will you be taken seriously by conferences, journals, potential collaborators or the media as an “independent scholar” without a university’s seal of approval?

But for humanities and social science scholars at least, the question is whether these hurdles are big enough to justify entering the university system and potentially ending up with no time left at the end of the day for their real passion.

This is why, as I’ve said to my friends, if your goal is pure research, the time to think and write about your own interests – as opposed to a structured career, ready recognition, teaching or working with business – then perhaps academia is not for you.

David Matthews is a Times Higher Education reporter based in Berlin.