Nathan Abrams

Professor of film studies, Bangor University

I’m planning to reread Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (Vintage). This has become more pressing given recent developments in the US (and here to some extent), and also because of the excellent adaptation currently being broadcast on Channel 4. In terms of new books, I’m looking forward to David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon: Oil, Money, Murder and the Birth of the FBI (Simon & Schuster), a true story that explores not only a strange site of murders of oil-wealthy native Americans in Oklahoma but also J. Edgar Hoover’s role in solving them and, in so doing, helping to establish the modern FBI.

Geoffrey Alderman

Senior research fellow, Institute of Historical Research

The upcoming centenary of the Balfour Declaration will no doubt be celebrated and mourned in equal measure by many in academia. I shall be preparing for this event by reading Leslie Turnberg’s recently published Beyond the Balfour Declaration: The 100-Year Quest for Israeli-Palestinian Peace (Biteback). This has been highly recommended as an insightful account that asks the subversive questions – which are, after all, the only questions worth asking. The possibility that Turnberg and I may differ – perhaps radically – in our explanations of why there is no Israeli-Palestinian peace is an additional incentive for me to understand what this celebrated medical professor (and Labour peer) has to say. I’ll also be rereading Irshad Manji’s The Trouble with Islam Today (St Martin’s Griffin). First published in 2004, this page turner is a brave, astute and authoritative riposte to those Muslims who insist on denying still the historic link between Palestine and the Jewish people.

Susan Bassnett

Professor of comparative literature, University of Warwick

I shall be reading Bela Shayevich’s translation of a collection of interviews by the 2015 Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich, Second-Hand Time (Fitzcarraldo). This book, like her previous work, gives a voice to ordinary people living in the aftermath of the great seismic shifts that have changed the lives of citizens of the former USSR. I shall also be reading the latest Alex Rider book, Never Say Die (Walker), before my grandson gets hold of it, as I am big fan of Anthony Horowitz.

Heike Bauer

Senior lecturer in English and gender studies, Birkbeck, University of London

I’ll be heading off to the Sallie Bingham Centre for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University this autumn for a new project on women’s graphic memoirs about violence. In preparation, I’ll be rereading Joan Smith’s 1989 classic Misogynies (Westbourne Press). Many of Smith’s insights into how “hatred” against women is expressed in everyday life remain scarily, infuriatingly current. I’m very much looking forward to finally being able to settle down with Sara Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life (Duke University Press), already a classic of intersectional feminism. Having only had the chance to dip into the book so far, I can’t wait to spend time with the “feminist killjoy” and her hope and resistance.

Devorah Baum

Lecturer in English literature and critical theory, University of Southampton

This summer I aim to read the always brilliant Stephen Cheeke’s Transfiguration: The Religion of Art in Nineteenth-Century Literature before Aestheticism (Oxford University Press), a major study of key figures in the development of a modern sensibility, expressed in near-religious devotion to certain kinds of art. Critically aware of the historical and cultural changes underpinning this development, this is a book that thinks seriously about the spellbinding impact of beauty on us. I also aim to return to Leonora Carrington’s wry and uncompromising The Debutante and Other Stories (Silver Press), which has just been republished with a foreword by Sheila Heti and an afterword by Marina Warner. This year is the centenary of Carrington, whose remarkable but often unsung role within surrealism, as a writer and an artist, is the subject of two films coming out this year, both a documentary, The Lost Surrealist, and a psycho-thriller named after one of Carrington’s own works, Female Human Animal, a title that says it all.

Joanna Bourke

Professor of history, Birkbeck, University of London

Sun and sadism. As I catch the hydrofoil to a Greek island, my bag will contain a dozen or so books on sexual violence. One of these is a large volume titled Psychopathia sexualis (1886), written by Austro-German forensic psychiatrist Richard Von Krafft-Ebing. It is a classic text. Krafft-Ebing was the first major scientist to publish a comprehensive analysis of the sexual perversions. He also coined the word “sadism”. In Krafft-Ebing’s hands, sadism was concerned less with the fantasies of the Marquis de Sade but became tightly bound to the brutal crimes of extremely violent men (and a few women). In its first English translation, Krafft-Ebing devoted nearly 50 pages to sadism, “lust-murder”, and “active cruelty and violence with lust”. But what about 21st-century sexual violence? Anastasia Powell and Nicola Henry are about to publish Sexual Violence in a Digital Age (Palgrave). They explore technology-facilitated sexual violence, including virtual rape, image-based sexual abuse (such as “revenge pornography”) and online sexual harassment. They focus on structural inequalities as well as the gendered harms caused by digital violence. In combination, these books remind me of how sexual aggression has changed over the past 130 years.

Rebecca Bowler

Lecturer in 20th-century English literature, Keele University

Terri Mullholland’s British Boarding Houses in Interwar Women’s Literature: Alternative Domestic Spaces (Routledge) came out in September last year, and I’ve been meaning to read it since then. A lot has been written about space and place in modernist literature, but the focus in this book is very specific: the boarding house is presented as a kind of median point between the safe domestic sphere and lodgings as new spaces for independent modern women. The blurb also promises coverage of three of my favourite writers: Dorothy Richardson, Jean Rhys and Virginia Woolf. I’ll read it, hopefully, in the liminal and sub-domestic space of my garden, with a glass of wine. I also think it’s about time I read Hannah Arendt’s 1951 work The Origins of Totalitarianism (Penguin). I’ve heard it praised as a history and analysis of its own time, and I’ve also seen it used as a tool for understanding some of the scary developments of our time. I feel, like many people, that I desperately need a toolkit.

Tara Brabazon

Professor of cultural studies, Flinders University

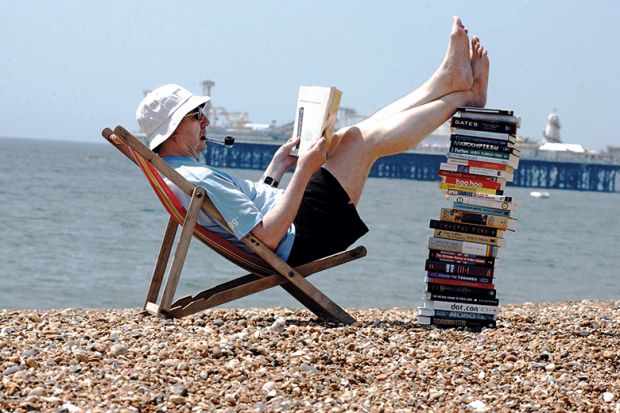

I’m not interested in desert island discs. I want books to read through the zombie apocalypse. I need to understand death, work, unemployment, underemployment and violent attacks on the self and society. Digitisation is not a metaphorical axe to a zombie’s head. Instead, the celebration of digitisation results in adding “2.0” to random nouns, as if a number offers an explanation. The two books that are carrying me through the zombie apocalypse are Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism (Polity) and Carl Cederstrom and Peter Fleming’s Dead Man Working (Zero). Both probe the slithering, creeping collusion between public and private, work and exhaustion, capitalism and death. As cars transform into terrorist devices and public housing explodes into flame through neglectful policies, planning and practices, we require books to understand the loss of agency, the loss of choice and the permanent revolution of fear, confusion and ignorance.

Josh Cohen

Professor of modern literary theory, Goldsmiths, University of London

I intend to return, after nearly two decades, to Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace (Routledge). Her enigmatic meditations on our proneness to fall into the lures of matter, to succumb to “gravity”, and on the possibilities of defying gravity and experiencing light or “grace”, have come to mind as I’ve been writing a book on inertia in psychic and cultural life. By way of apparent contrast, but in fact teeming with intriguing connections, I will be reading Chris Kraus’ novel Torpor (Tuskar Rock), a kind of prequel to her brilliant and notorious I Love Dick . I was late to the I Love Dick party but intend to make up for lost time and devour my way through the rest of this amazingly audacious writer and thinker’s back catalogue.

Sir Cary Cooper

50th anniversary professor of organisational psychology and health, University of Manchester

There are two books I will be reading by the pool in the Algarve in August, grandchildren permitting! The first is Monica Worline and Jane Dutton’s Awakening Compassion at Work (Berrett-Koehler). With “stress” now the leading cause of sickness absence and presenteeism in most workplaces, managers and others in organisations seem to have lost their capacity to be empathetic and compassionate. Often we see on the national news stories of the appalling treatment of patients in hospitals by nurses or among carers in care homes. The book explores issues of compassion and empathy, and what can be done to cultivate them. My next read is partly related because it goes back to 1937, just before the German annexation of Austria. Robert Seethaler’s The Tobacconist (Picador) explores the perceptions and feelings of a 17-year-old from the country who goes to Vienna to work in a tobacconist shop and sees at first hand the cruelty and inhumanity of the Germans. He meets Freud and develops a close relationship with him, and begins to understand (empathetically) what the Jews of Austria are going through. As someone from an Eastern European Jewish family, I am particularly interested in reading this book.

John Cornwell

Director, Science & Human Dimension Project, Jesus College, Cambridge

Ever since school I’ve returned again and again to Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. It is a poem of anguish, grandeur and complexity that invites the mind to wind and unwind again the golden thread that leads through so many mysterious places. Malcolm Guite, poet, literary critic and chaplain of Girton College, Cambridge, has written Mariner: A Voyage with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (Hodder). It promises a new departure on that strange journey. I can’t resist, even at 480 pages! Because of the Italian earthquakes, my thoughts have been much in Italy, not the Italy of Chiantiland, but of harsher, more sober, yet no less inspiring, realities. Every few years I return to Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli (Penguin), the poignant story of the author’s years in a southern hilltop village during the late 1930s. Levi, a physician, had opposed the fascist regime and was exiled to this poverty-stricken place where austerity and fear of earthquakes are a permanent condition. He sets up a medical practice. His love for the people, their courage and endurance, shines through. When he finally returns to the north, he is reminiscent of the Ancient Mariner, a sadder and a wiser man.

Sarah Cox

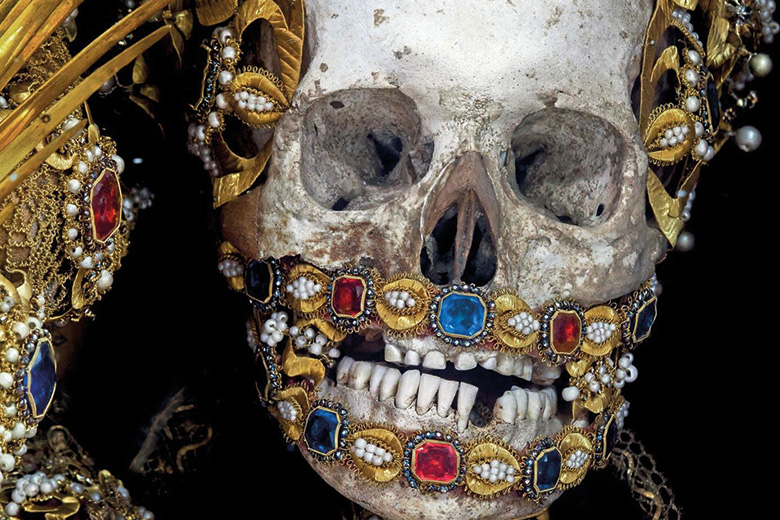

Senior media relations officer, Brunel University London

This summer I’ll be delving into the latest morbid photography tome/tomb by Paul Koudounaris, Memento Mori: The Dead among Us (Thames and Hudson). No one else makes human remains look quite so beautiful, with such absolute respect. His writing and taboo-defying images are a real eye-opener to the different ways cultures around the world respond to death. It’s also a gorgeous object to have on my coffee table, bound in blue silk – a very generous gift from the brilliant medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris, while I eagerly await her first book, The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine (out in October). I plan to return to the 1979 biography Allen Lane: King Penguin (Hutchinson) by Jack E. Morpurgo, having first picked it up years ago but I no doubt got distracted by something else with a nicer cover. Late last year, by coincidence, I moved into a wing of the publishing pioneer’s former home a few miles from my office at Brunel. My landlord reckons that they held a launch party for Lady Chatterley’s Lover there in 1960, and while I’m yet to find evidence, I won’t let that get in the way of a good story.

Nicola Dandridge

Chief executive, Universities UK, and recently appointed chief executive of the Office for Students

I am looking forward to reading a non-British perspective on the European Union in Yanis Varoufakis’ Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment (Bodley Head). The book should certainly make for an invigorating read, whatever you think about his politics and approach. I have just started Arundhati Roy’s wonderful The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Reviews have compared Roy’s unflinchingly intelligent synthesis of the personal and the political to George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I read Middlemarch when I was in my teens and all I remember of it now is a rather depressing plot where everything goes wrong. I am looking forward to rereading it this summer and appreciating it in rather more depth.

Lennard Davis

Distinguished professor of liberal arts and sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago

This summer I took a trip to Lithuania where my Jewish grandfather and many generations lived. So I’ve been reading rather downer books about the murder of the Jews in Eastern Europe. Not exactly beach reading material. But one of the books that I think is in the genre but totally readable, in fact a real page-turner, is the graphic novel by Rutu Modan called The Property (Jonathan Cape). I don’t generally read graphic novels, but this one is not only visually compelling but is both a love story and a tear-jerker. It’s about a granddaughter and grandmother who return to Poland to find the property owned by the rather cantankerous elder before the Second World War. The book is alternately funny, sad, poignant and, yes, emotional. Prepare to laugh and bring your Kleenex. Since I’m on a Zola jag, I’ll also be reading one of the Rougon-Macquart series I haven’t read. It will be either (or both) The Belly of Paris about Les Halles, the food market, or Money, which is about the financial exchange. While neither subject seems appropriate for the days of wine and roses, I trust that Emile will spin out a tale of great interest from the rather mundane subject matter he researches, as he did with the coal mines of Germinal and the department stores of The Ladies’ Paradise.

Sir David Eastwood

Vice-chancellor, University of Birmingham

My pile for summer reading grows, and I surreptitiously glance at my purchases anticipating immersive pleasure. At the top is Fritz Trümpi’s The Political Orchestra: The Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics during the Third Reich (Chicago), a magisterial exploration of the impact of the Nazi regime on the role, repertoire and personnel of the two orchestras. This traumatic transformation had profound and enduring consequences for both orchestras and indeed for the German tradition. I will then return to Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, whose lyricism and dramatic power make it one of the world’s greatest novels. Tears will overwhelm me as I read the closing paragraph with its incandescent images of beauty, love and hope, which ultimately endure, transcend and transfigure. I know of no more moving passage in literature.

Alun Evans

Chief executive, British Academy

The book I’m returning to is Wuthering Heights. Over the past year I have started to walk all of the Pennine Way. One wet afternoon I came over the hillside near Haworth and reached Top Withens, the ruined house on which, supposedly, Emily Brontë based the home of the Earnshaw family. It is such a bleak place that I would like to remind myself of the story and think of why she chose this location on which to base her novel. The new book I am looking forward to is Lenin on the Train (Penguin) by British Academy fellow Catherine Merridale. I heard her give a compelling talk at the Hay Festival this year. The book tells the story of 100 years ago, when Lenin made the journey from Zurich to Petrograd (St Petersburg) through Germany in the famous “sealed train”. The Germans facilitated the journey because they thought that helping Lenin foment revolution in Russia would help in their fight against the Russians on the Eastern Front. As preparation for writing the book, Merridale recreated Lenin’s 3,000-mile plus journey through Germany, Sweden and Finland, a journey that – literally – changed the world.

Mary Evans

Centennial professor in the Gender Institute, London School of Economics

My new book is to be Susan Bordo’s The Destruction of Hillary Clinton (Melville House). I am not sure that I will agree with all her conclusions (the back cover suggests a central emphasis on sexism rather than a combination of factors), but this author is always interesting. I am just very sorry that she had to write this book. The book that I shall return to this summer – although I have to admit not all of it – is Georg Simmel’s The Philosophy of Money (Routledge). But I’m working on contemporary detective fiction, and there are sections of Simmel’s book (for example, “Money in the Sequence of Purposes”) that I think are very relevant to my present subject. Not to mention, of course, more immediate UK politics.

Graham Farmelo

Fellow of Churchill College, University of Cambridge

I’ve been slightly depressed to hear that so many of my author-friends are being steered towards writing not full-length books but short introductions to topics that publishers regard as “hot”. But I have to admit that several of these mini-books really are rather good, and I can’t wait to get started on James Hawes’ promising The Shortest History of Germany (Old Street Publishing). Summer’s long evenings are perfect for reading classics that demand a lot of concentration and so are often more praised than read. But I know that rereading Leo Tolstoy’s short stories – especially those collected in The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories – will be a joy. The translators, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, have refreshed so many Russian classics for readers who have the time to tackle them.

Matthew Feldman

Professor of the modern history of ideas, Teesside University

I’m reading Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 It Can’t Happen Here, reprinted this year (Penguin) – and selling like hotcakes following Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration. Offering a standard Marxist view of fascism long ago historiographically discarded, the novel imagines business as the reactionary hand behind a quasi-legal regime; a mix of Nazi racism and fascist economic corporatism, encrusted with paramilitary violence. Liberals, “cramped by a certain respect for facts which never enfeebled the press-agents for Corpoism”, endure concentration camps and summary executions. Much of Congress is arrested and then Mexico invaded, climaxing in a second civil war. The journalist Doremus Jessup acts as dissident protagonist, watching with horror as a “program for revitalizing the national American pride” turns into bloody tyranny. Jessup ruefully concludes: “It can happen here.” Yet not precisely that way here and now, surely. An enfeebled liberalism, perhaps, but turbo-capitalists in jackboots? A more fitting account could substitute “Western” Muslims today for American Jewry. This is a fluid subject, as I am discovering in Douglas Pratt and Rachel Woodlock’s collection Fear of Muslims? (Spinger), mooting the overdue counter-term “Islamoprejudice”. The contributions are among the most detailed and wide-ranging to date in this comparatively and, regrettably, new field of study. Old wine for new bottles – and that includes its sickening, “mainstreaming” discourse.

Felipe Fernández-Armesto

William P. Reynolds professor of history, University of Notre Dame

Summer’s lease hath so short a date that I hardly expect to look up from my keyboard before it’s over. Optimistically stacked by my bedside, however, La libertà, per esempio: Questioni mediterranee e idee liberali (Marcianum) by Paolo Luca Bernardini will be on top of the new books. His is one of the best-informed voices in contemporary Italian libertarianism, and he always has fresh things to say on Mediterranean topics. Rereading, except of poetry and scripture, is, to me, usually a waste of time, but relevance to a book I’m writing (on engineering in the Spanish empire – I know it sounds boring but I’m going to make it out to be the fulcrum of global history) is driving me back to a former favourite: Thornton Wilder’s perplexingly amusing disaster-novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey.

Patrick Finch

Bursar and director of estates, University of Bristol

Having spent a lifetime in the land and property industry, I am always intrigued to uncover old title deeds and plans, with their wonderful descriptions of places, roads and byways often now lost in the passage of time. So I will be reading Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks (Penguin), which seeks to document the lost language of place. The book promises a fascinating blend of nature, culture, language and history and includes a glossary of terms that were once held dear in far corners of the British Isles. A quick glance reveals “letty” from my own home in Somerset, meaning rain that impedes outdoor working. I hope that our estates office will not be experiencing too many letties this summer. I often return to P. G. Wodehouse and have in my bag The Code of the Woosters. I wonder whether our campus still harbours any Gussie Fink-Nottles, Madeleine Bassetts or Roderick Spodes? Fairy dust may be in short supply just now, but it remains a wonderful place to pursue the study of newts.

Adrian Furnham

Professor of psychology, University College London

I spend a good part of every day reading and writing. I have developed painful arthritis in both hands as a consequence of this. Perhaps it is God’s way of telling me to write less and that “publish or perish” is a myth. So reading books can be something of a busman’s holiday. And yet I particularly enjoy a few hours reading after an early morning swim in an agreeable subtropical resort. For years I read books that my wife had brought along: nearly always fiction, which I rarely indulge in. But a visit to Amazon generally leads me to buying more and more books. I go looking for one and buy half a dozen. So piled against my study wall is a three-foot-high pile of books. I plan to read two: very different from each other. The first is DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing), the updated 2013 fifth edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the American Psychiatric Association’s classification tool. It cost more than £90.00 and is a surprisingly good read. The other book is Other Men’s Flowers: An Anthology of Poetry by Lord Wavell, great general and sometime viceroy of India. I find a great deal of solace in great poems…and look forward to 20 minutes a day with this classic.

Valérie Gauthier

Associate professor, HEC Paris

This summer I will read with particular attention a promise that has come true and is bringing a wave of joy and hope in France: Emmanuel Macron’s Révolution (XO Editions). Written before the man turned around politics and became the inspirer of a new generation of change makers, Macron (pictured inset right) traces the premise of a revitalised France and a rejuvenated Europe. On a very different note and to bring music to my ears, I will dive into the Complete Poems of Elizabeth Bishop (Chatto and Windus), which were a great source of inspiration to me as a student in the US. The voice of Bishop and her incredible sense of observation have always been a driver for my research into human behaviours and the capacity for leaders to use their senses more effectively to capture the reality of their environment. Sounds, sights, touch, smells, taste, all senses melting in synaesthesia and correspondences to be more perceptive and effective, lead the way to understanding nature and people for who they are in their uniqueness. Respect for others in their differences is a source of wealth that I believe the revolution brought by La République en marche will also instil.

Eliane Glaser

Senior lecturer in creative writing, Bath Spa University

Recent attacks by billionaire property tycoons and Oxford-educated government ministers on “experts”, professionals and intellectuals have prompted me to write a defence of these so-called “liberal elites”. The urban theorist Andy Merrifield denounces experts from a rather different perspective in his new book The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love (Verso), associating them with “box-tickers”, “bean counters” and other guardians of paid employment and commercialised leisure. I’m on Merrifield’s side politically, so I look forward to his critique nuancing my own. I’ll also be returning to the late 19th-century lectures and essays of William Morris, to see if his defence of high aesthetic standards for all can be updated for a digital age in which the levelling-down, or “democratisation”, of culture and education is used as a fig leaf to conceal soaring inequality.

Richard Joyner

Emeritus professor of chemistry, Nottingham Trent University

My choices show American politics at its worst and American journalism at its best. I’m hugely looking forward to P. J. O’Rourke’s account of the 2016 presidential election, How the Hell Did This Happen? (Grove). I expect this practised satirist to skewer everything and everyone from the Iowa caucuses to the inauguration, with special reference to “crooked” Hillary and “fake news” Donald. Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s account of the Watergate affair, All the President’s Men (Bloomsbury), is a true classic. Even on a third or fourth reading, I know that I will be gripped and sometimes surprised.

John Kaag

Professor of philosophy, University of Massachusetts Lowell

I am going to spend my summer breezing through one book and toiling over another. The breeze – I suspect – will be Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking (Granta). She’s such a lovely writer and walking such a natural, expansive subject, I’m sure I’ll move through it quickly. Here is the toil: Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra. Another great walker, but Nietzsche is never breezed through. I suspect it will take me many days, broken by my own wanderings around New England. I am writing a book called Hiking with Nietzsche – so both reads will be helpful. Summers are meant for reading, but also walking. I can’t wait.

Read part two of our 2017 summer reads

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login