Are you a super-productive academic? And if not, can you turn yourself into one?

These are the questions that are raised by the striking finding that one in 10 of Europe’s academics apparently produce nearly half of its research output.

Marek Kwiek, director of the Center for Public Policy Studies at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland, bases this statement on an analysis of responses given by 13,908 research-active academics in 11 countries to two European research projects, CAP and EUROAC.

According to academics’ accounts of their research output, just 1,583 highly productive academics (11.4 per cent of the sample) were responsible for producing 32,706 out of 71,248 journal articles and book chapters (45.9 per cent) over a three-year period.

The UK-only results broadly reflected the Europe-wide picture: 89 of 1,467 researchers who responded (11.5 per cent) produced 1,740 of 4,215 papers (41.3 per cent).

The analysis indicates that the top echelon of academics was even more prolific: across the 11 countries, the upper 5 per cent produced 33 per cent of publications.

Professor Kwiek acknowledges that a researcher’s prolificacy cannot be assumed to be an indicator of the quality of their publications. But since it is often argued that there is a correlation, and given that advancement and esteem are often based on publication, he has set out to explore the characteristics of this elite group.

The first finding is that the group has certain demographic characteristics. The most productive researchers tend to be older: for example, in the UK, their average age is 46.3, compared with 37.6 among other academics.

They are more likely to be male and, significantly, this appears to go beyond the continuing under-representation of women in academic staff in general: the proportion of male staff who become top performers is considerably higher than the proportion of female academics.

However, super-productive academics also appear to have a distinct set of work patterns, Professor Kwiek says.

They work harder, the survey suggests. German top performers work the longest hours, putting in an extra 10.2 hours each week – equivalent to 66.3 additional working days every year. British top performers put in an extra 7.3 hours per week.

Super-productive academics’ jobs are research-focused, the survey says: having a job that is largely teaching in effect excludes academics from the elite category.

Other areas in which the most prolific academics excel is research collaboration, both internationally and domestically, and their research is more likely to be international in scope.

They are more likely to sit on national and international committees, to be a peer reviewer, and to be the editor of journals or book series.

Professor Kwiek concludes that the European academic profession is “highly stratified” and that the elite are a “highly homogeneous group of academics whose high research performance is driven by structurally similar factors which cannot be easily replicated through policy measures”.

“With the increasing role of individualised competitive research funding in most European higher education funding architectures...the role of research top performers in national systems is bound to increase in future,” he concludes.

Professor Kwiek’s findings are published in an article published online by the journal Higher Education, and in a chapter of the forthcoming book The Transformation of University Institutional and Organizational Boundaries, edited by Emilia Primeri and Emanuela Reale.

Appointments

Lancaster University has named five new professors from the worlds of business, academia and conservation at its Environment Centre. Paul Carmichael, a senior toxicologist from Unilever, Jon Grey, research and conservation officer for the Wild Trout Trust, and Rob Lamb, chief scientist at environmental and engineering firm JBA Consulting, have all joined. Júlio Louzada, professor of ecology at the University of Lavras in Brazil, and Felix Wäckers, director of R&D at Biobest, a company producing pollinators and biological control agents, have also been made professors.

Kate Tedford, head of the University of the West of Scotland’s Graduate School, has been awarded a personal professorship. Professor Tedford has more than 20 years’ experience in the sector and has previously worked at the universities of Strathclyde and Edinburgh.

The Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama has made Simon Phillippo head of keyboard studies. He will take up his appointment following the retirement of Richard McMahon at the end of this academic year.

Craig Jeffrey, a leading expert on contemporary India and professor of development geography at the University of Oxford, has been appointed director of the Australia India Institute, based at the University of Melbourne.

POSTSCRIPT:

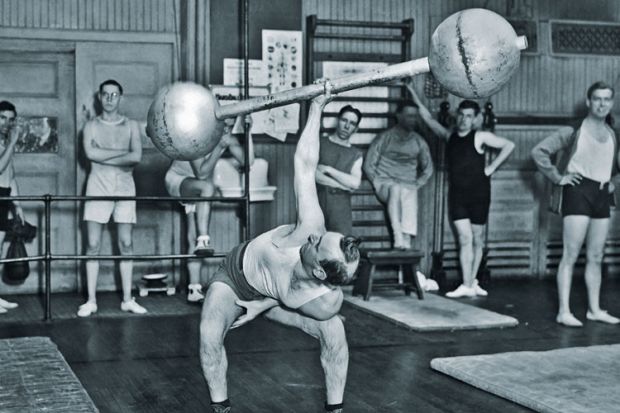

Article originally published as: Doing the heavy lifting: the academy’s super troupers (9 July 2015)

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login