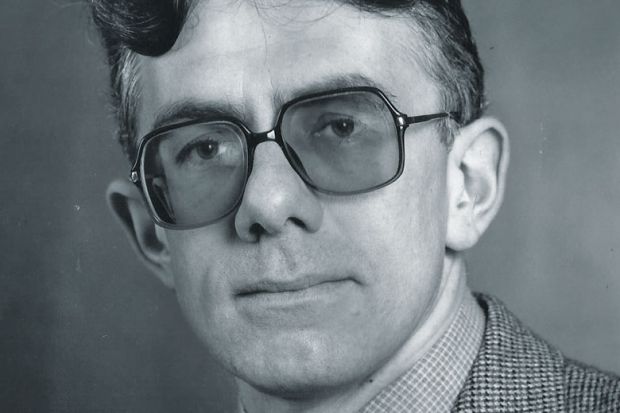

Peter Wright was born in Hull on 6 February 1941, although the family moved when he was six weeks old after an unexploded bomb was found in their garden.

He attended a number of different schools and studied sociology at the London School of Economics (1962). After a short period of postgraduate work, he became a lecturer at the University of Leicester, then one of the few in Britain to have a department of sociology. While there, he was briefly arrested in 1964 for organising a sit-in to break the “colour bar” in a local pub.

Over the following years, Dr Wright gained experience right across the spectrum of British higher education. He taught at Leeds College of Art and then joined the Bristol College of Commerce as a lecturer in sociology and politics shortly before it became a polytechnic in 1969.

He moved on to Sheffield Polytechnic as a senior lecturer in sociology in 1971 and was appointed head of the department of applied social studies at the then Portsmouth Polytechnic in 1982. Here he was responsible for incorporating the local schools of nursing and developing training for clinical tutors. He also acquired a PhD (1984) for a thesis about the rise of science in 17th-century England.

Moving out of academia, Dr Wright became HE adviser at the Manpower Services Commission. From there it was a natural step in 1992 to the new Higher Education Quality Council, where he wrote a highly influential essay that helped to redefine what we mean by “graduateness” and streamline the national qualifications framework.

When the HEQC became the Quality Assurance Agency in 1997, he took on the role of deputy director and helped to oversee the transfer from London to Gloucester. Although ill health forced him to retire from full-time work in 2004, he continued teaching, lecturing and supervising.

Roger Brown, former head of the HEQC, described Dr Wright as “always kind, courteous and supportive, with a lovely genial twinkle”. His many interventions into debates about higher education were always notable for “his knowledge of the sector, not only traditional areas of the curriculum but also newer ones like nursing; his rigorous thinking; his understanding of the issues, based on both intellect and experience; and his ability to convey his ideas in persuasive and often elegant prose”.

Dr Wright died of pneumonia and advanced Parkinson’s disease on 19 August 2016 and is survived by his wife Christine, their two sons, three daughters from an earlier marriage, 13 grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login