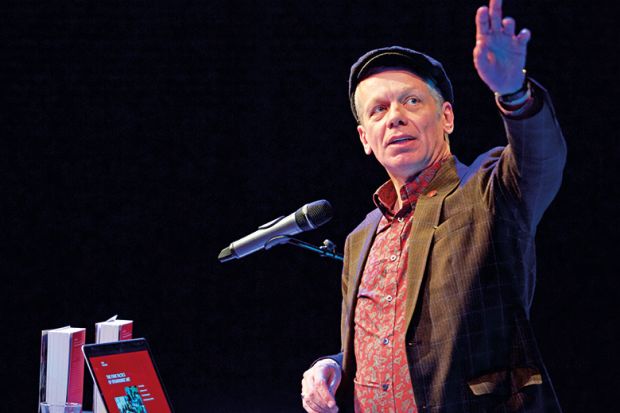

Richard Barbrook is a senior lecturer in the department of politics and international relations at the University of Westminster. He has written widely about radio, the internet, political theory and games. He was closely involved in the creation of the Corbyn Run video game, which went viral just before the 2017 UK general election. Since the end of last year, he has been working for the Labour Party as a digital democracy and games strategist.

Where and when were you born?

Nottingham in 1956, but I spent most of my childhood in Loughborough and Canterbury.

How did you experience your undergraduate days?

It was Cambridge in the late 1970s and I got a very strong dose of class hatred. I really didn’t like the oligarchy reproducing itself. I had read Lewis Namier at secondary school, and he writes about the Whig oligarchy in the 18th century. They were still there at Cambridge! They had just been reproducing themselves generation after generation. It was quite a shock.

What were your most memorable moments at university?

There was a man called Walter Ullmann who taught medieval critical philosophy at 10am – and there was standing room only. I went every week, regardless of how wasted I’d got the night before, because he was brilliant. I realised later that he was the first Hegelian Marxist who taught me, so I think that he shaped me intellectually. The other memorable thing was a place called the Midland Tavern, run I think by Jamaicans, that had a disco with lots of reggae and funk.

What do you mean when you call yourself ‘part of the punk generation’?

It’s an attitude thing: not taking any nonsense and not being deferential to authorities. It meant that you could “do it yourself”. You could make your own band, make your own family, make your own film. I got very involved in pirate and community radio.

How did your research interests shift from radio to the internet?

I went to Paris quite a lot because they had free radio and something called Minitel, a sort of protointernet. So I was just waiting for it to arrive. As soon as it arrived, I got a job teaching about it.

What led you to give serious academic attention to games?

I shifted from the media to the politics department and wanted to write a book about [the French ‘situationist’ political thinker] Guy Debord. I then discovered that he had made a war game and we started playing it around Europe, Russia and Brazil, and that became a means of talking about situationism in a different way.

Why do games make a good teaching tool?

It’s an immersive teaching method, teaching by doing. I have friends who work in the military or the National Health Service and they use games for contingency planning and for training. But in both politics and academia there’s a bit of resistance, as if games were just for children. We did a game in class about the creation of the 2010 coalition. Games reveal things that just reading books can’t. Games can show you that history and politics are a lot more fluid than they appear in texts, where people tend to say that because something did happen, it had to happen.

How did you get the chance to apply your research interests to practical politics?

I was very involved in Labour politics in the 1980s, which is how I met [shadow chancellor] John McDonnell. And I was involved in the campaign by the Labour left that helped Jeremy Corbyn become party leader. Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s presidential campaign in France made a laptop game, so I suggested that the Labour Party should make a game too [Corbyn Run]. It took off like a rocket because of viral marketing, even though it wasn’t part of the official Labour campaign.

What are your current projects with the party?

We created a game for the shadow Treasury team devoted to contingency planning for their first 100 days in office, looking at scenarios such as a run on the pound. We are also developing “mega games” for training party activists about what happens when the party is in power, the compromises that you have to make, the disputes about which bits of the manifesto get implemented and so on. We’re obviously not making it about a possible Corbyn 2018-19 government, because that would be a hostage to fortune, so we are using the 1983 manifesto to think through what it will be like to have a left-wing Labour government.

What are the best and worst things about your job?

The best? I get really smart, interesting students from around the world. [Their different perspectives] make you question your own politics, which is good. The worst thing is the bureaucracy, which has got worse and worse – they measure everything.

What keeps you awake at night?

Writing. I like writing until dawn.

What do you do for fun?

Dancing. The one thing that I’ve kept from my punk youth is going to clubs.

What’s your biggest regret?

That Labour didn’t win the 1983 election – now we’re recreating it as a game as if the party did win.

If you were a prospective student facing £9,000-plus fees, would you go again or get a job?

Of course I’d go – and then I’d emigrate to Berlin or Barcelona.

If you were universities minister for a day, what policy would you introduce?

I would abolish tuition fees and severely cap the amount that universities can spend on administration.

Do you live by any motto or philosophy?

One day, we – the left of the Labour Party – will win.

What would improve your working week?

More sunshine. If we had the weather of May through to September all year round, London would be perfect.

matthew.reisz@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Aletta Norval has been named deputy vice-chancellor at Anglia Ruskin University, taking responsibility for education and student experience. Originally from South Africa, the political theorist came to study at the University of Essex, before joining its department of government and eventually becoming pro-chancellor (education). Iain Martin, Anglia Ruskin’s vice-chancellor, said that Professor Norval “brings a wealth of experience and will provide strong educational leadership for our university”. “Her new portfolio brings together the academic and the non-academic aspects of the student experience so that we ensure delivery of a university education that meets the needs of our students and the region,” Professor Martin said.

Warren Manning and Keith McLay have been appointed pro vice-chancellor deans at the University of Derby. Dr Manning has joined the College of Engineering and Technology from De Montfort University where he was pro vice-chancellor and dean for the Faculty of Business and Law. Professor McLay will lead the College of Arts, Humanities and Education after nearly four years as dean of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Canterbury Christ Church University. Kathryn Mitchell, Derby’s vice-chancellor, said that Dr Manning and Professor McLay were “both excellent leaders who bring very distinct skills to their roles”.

Jeremy Tavaré will take up the role of dean when the University of Bristol’s Faculty of Life Sciences is launched in August. He is director of research (health and life sciences) at the university.

Constance Mallette has been named vice-chancellor for finance and administration at Winston-Salem State University in North Carolina.

Bernard Silverman, a former chief scientific adviser to the Home Office, has joined the University of Nottingham as professor of modern slavery statistics.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login