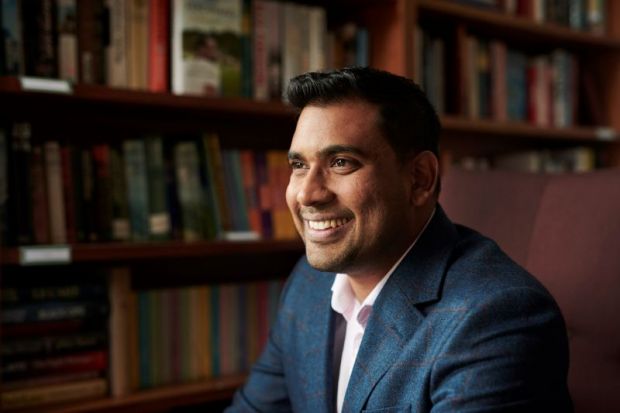

Michael Muthukrishna is an associate professor of economic psychology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He runs a multidisciplinary lab, spanning data science, economics and psychology research. His first book, A Theory of Everyone: Who We Are, How We Got Here and Where We’re Going, was published in September.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Sri Lanka in 1987, spent my childhood in Botswana, Papua New Guinea and Australia, and lived in Canada, the United States and most recently Britain.

How has this shaped who you are?

When you live in so many places, you see how we differ and how we are connected. In Sri Lanka, I learned how two peoples who looked so similar to outsiders – Tamils and Sinhalese – could be so divided. My memories from Botswana, South Africa’s northern neighbour, are filled with the dusty streets of Gaborone, camping deep in the Kalahari Desert under the unobstructed majesty of the Milky Way, and the exhilaration and trepidation as South Africa transitioned from apartheid. As a young boy in Papua New Guinea, I lived 500 yards south of the parliament, with front-row tickets to gunfire, looting and explosions, which turned the capital, Port Moresby, from an everyday level of deadly threat to a violent coup that later became known as the Sandline Affair. I was in London during the 2005 bombings, a coordinated attack designed to terrorise ordinary British people on an ordinary Thursday on their ordinary commute to work. What struck me most was the identity of the bombers: ordinary British citizens. I remember [Mohammad Sidique] Khan’s thick Yorkshire accent as he explained “until we feel secure, you will be our targets”. The “you” he refers to in his grainy video are his fellow Brits; the “we” are a people who live thousands of miles away in countries that he had only briefly visited yet to whom he feels a greater connection. As I describe in my book, these were formative memories set against my otherwise unremarkable, if peripatetic life.

Tell us how your first book came about.

For the last two decades I’ve been obsessed with understanding the differences and connections I’ve seen over my life. Why was Botswana less corrupt and on many metrics more successful than South Africa? Why was Papua New Guinea so much poorer and less peaceful than Australia? What are the differences between the multicultural and immigration policies of Australia, Canada, the United States and the countries of Europe? Why is American democracy teetering? Why have civil conversations in which we agree to disagree given way to enraged moralising aimed at those who hold beliefs different from our own? Why are we in the midst of yet another economic crisis? One great piece of advice I was given: only write a book when it’s bursting out of you; when you can’t not write the book. That’s how it felt. I desperately wanted people to know the answers to these questions: how we got here and where we’re going (or could go).

The book is grounded in a multidisciplinary approach and also in the field of cultural evolution. How did this inform the writing?

Working across multiple disciplines has allowed me to take a non-disciplinary – or perhaps “undisciplined” – approach to answering these questions, pulling on strands deep within psychology, economics, biology, anthropology and elsewhere, tying them together into a tapestry that reveals who we are, how we got here and where we’re going. The book is written in such a way that you don’t have to trust me because some study said I was right; given rates of replication and recent fraud cases, you should be sceptical about isolated evidence alone. Instead, I try to show readers rather than tell them, so that once you see the links between energy, innovation, cooperation and evolution, you can’t unsee them. Once the insights from these disciplines are woven into a tapestry, that tapestry is almost obvious, its implications unmissable.

You’ve also advised the likes of Uber and the UK government. What are the key things these stakeholders want to know about the future?

The theory of everyone I use in my work leads to new answers to old problems in innovation, corruption, cooperation and the navigation of diversity and cross-cultural differences. Stakeholders in business and government want to know how to improve in these areas with this powerful new toolkit.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I was interested in big questions but I also like to manage risk, so I enrolled in a dual degree at the University of Queensland in Australia. I enrolled in an engineering degree, which seemed like a secure, well-paid career with international accreditation – a great fit for someone with itchy feet. Engineering was fun and I was good at it – but engineering alone didn’t seem like it could answer the questions that preoccupied me. So in parallel with courses on calculus, discrete maths and machine learning, I took economics, political science, biology, philosophy and psychology, which I majored in. This background was useful for my future studies.

What divided your life into a ‘before’ and ‘after’?

The decision to leave a career in engineering to apply those skills to some of the challenges I could see ahead – for example, the challenges created by the climate crisis. It seemed unlikely to me that we would slow the economy to save the planet in a world where every country was trying to outcompete every other country, every company was trying to outcompete every other company, and every person wanted a better lifestyle than their neighbours. If your theory for improving the world requires changing human nature or fundamental evolutionary principles, you’re either going to need a dangerous level of coercion or are doomed to failure. It made sense that we should still try to reduce our carbon footprint as many have advocated, but it made even more sense to also start preparing for a climate-changed world. I now realise that the key to conservation and tackling climate change isn’t scarcity or degrowth; it’s the next level of energy abundance.

CV

2005-10 Bachelor’s degrees in engineering and psychology, University of Queensland

2012 Master’s in psychology, University of British Columbia

2012-15 PhD in psychology, University of British Columbia

2015 Postdoctoral fellow, department of human evolutionary biology, Harvard University

2016-20 Associate, department of human evolutionary biology, Harvard University

2016-20 Assistant professor, department of psychological and behavioural science, London School of Economics and Political Science

2020-present Associate professor, department of psychological and behavioural science, London School of Economics and Political Science

tom.williams@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Michelle Lincoln has been appointed the new deputy vice-chancellor, academic at the University of Canberra, replacing Geoff Crisp, who retires at the end of October. Professor Lincoln is currently the executive dean of the Faculty of Health at Canberra, having previously served as deputy dean, learning and teaching in the Faculty of Health Sciences at The University of Sydney. She said she would use the role to “build connections across the faculties and professional staff teams and foster multidisciplinary teamwork, courses and research”.

Samir Mayekar has been named managing director of the University of Chicago’s Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, effective from November. A former deputy mayor of the city of Chicago, Mr Mayekar previously served in the Obama administration, where he was part of the White House’s national security team. The university’s president, Paul Alivisatos, said Mr Mayekar “brings a marvellous energy to building partnerships and is creative and thoughtful in his approach, and the university will benefit from his talent, experience and commitment”.

Jeanette Rotchell has been named the new director of research at the College of Health and Science at the University of Lincoln. A professor of environmental toxicology, she will join Lincoln from the University of Hull, where she is currently associate dean for research and enterprise.

Cathy Gower will be the next dean of the Faculty of Education and the Arts at the University of Winchester. Currently dean of the School of Education at the University of Brighton, she is due to take up her new post in January.

Paul Oberholster has been promoted at the University of the Free State (UFS) in South Africa, becoming its dean for the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences. He is currently the director of the Centre for Environmental Management.

Marcel Dinger is joining The University of Sydney as its new dean of the Faculty of Science. He moves from the University of New South Wales, where he is currently the head of school for biotechnology and biomolecular sciences.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login