Two years ago, the Open University, in partnership with the Midlands Arts Centre, organised a screening of The Stuart Hall Project, John Akomfrah’s absorbing documentary about the cultural theorist, writer and public intellectual who is probably also the OU’s most distinguished former academic.

All the cinema seats were sold, and the post-film discussion in an adjacent room was heaving with more than 100 people, some sitting on the floor with a bottle of beer or a glass of wine. For some, it was a throwback to the days of the University of Birmingham’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS), Hall’s previous academic home, which closed in 2002. At the CCCS, Hall inspired many exciting projects: collaborative books, feminist workshops and conferences and a few unfinished PhDs. A long way from today’s narrow academic posturing or the insular world of higher education managerialism, the CCCS shared the OU’s commitment to intellectual promiscuity, innovation and scholarship aimed at a wider public.

The discussion involved a heady mix of reminiscence and debate involving CCCS graduates and ex-colleagues, the playwright David Edgar and the OU’s own John Clarke, a former collaborator of Hall’s at both institutions. Among the contributors from the floor was a black police officer who recalled talking to Hall at Open University summer school about the impact that his seminal Policing the Crisis had on his approach to law enforcement. This debate (which I chaired) was one of the highlights of my work in Birmingham and an example of the kind of diverse academic communities that, throughout its history, the OU has been uniquely capable of building.

I’ve no idea whether Keith Zimmerman, the OU’s university secretary, knows anything of Hall or of his legacy for the OU. It is unlikely to have had any bearing on his decision, as convener of the OU’s “Locations Review”, to close seven English regional centres, including the one in Birmingham, at the end of next year. For today’s higher education leaders, the language of organisational change, restructuring and “moving forward” seems to take precedence over institutional ethos.

However, those concerned about the future of the OU should not underestimate the lasting public appeal of Hall, the OU’s roots in adult education and its wider local links in the regions. Hall, after all, was a figure at the cutting edge of cultural change. Even on the sad day last year when his death was announced, he was trending on Twitter. Those of us who produce multimedia modules or support students locally through a mix of face-to-face and online teaching strategies reject the claim that we are looking backwards or “standing still”, as the OU’s new vice-chancellor, Peter Horrocks, has implied that those fighting the changes are doing.

Then there is Birmingham itself. England’s second city has felt increasingly marginalised in the wake of the “Northern powerhouse” and London’s domination. But Birmingham is going places again. The BBC office, moribund and hit by cuts a short time ago, now promises a digital innovation unit to reach younger audiences and new learning avenues across different media platforms. More widely Birmingham, along with West Midland partners, has just announced a £1 billion deal to expand the business district, improve training and transport and establish a regional mayor. The region is expanding, and there is need for more education.

For many years, the OU regional centre in Birmingham has offered students a tutorial venue, an examination centre, study and careers advice, as well as hosting public events and staff parties – including an annual Christmas pantomime. Many of the 55 staff members whose jobs are threatened by the closure announcement have given long years of service, even taking OU degrees themselves as a sign of their dedication.

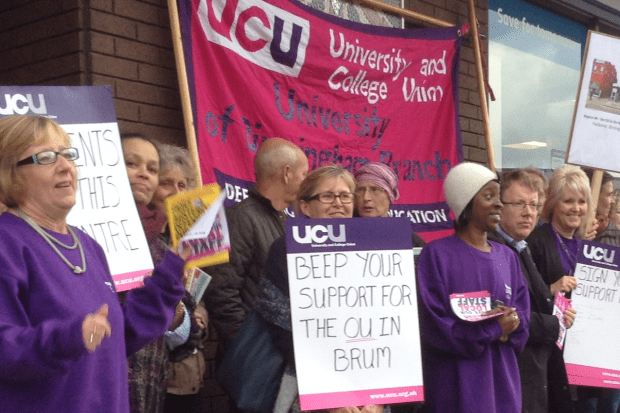

The OU management’s justification for the closures is that the regional centres are rarely used by students and that the same services can be provided in fewer centres. This statement was received with some surprise by colleagues in the Birmingham office, who feel that their knowledge and expertise cannot be replaced by a call centre. The last thing they would have expected was to be spending their lunch hour rallying public support to keep the office open. This week has brought the first ever strike by OU staff against its own management after the OU council approved the closures, ignoring the advice of its senate, the university’s highest academic body, which had already rejected them.

Even in the protests, Brummie humour was evident. The second lunchtime rally coincided with a charity Strictly Come Dancing event in the office, and presented an opportunity for some dancers to post a placard message to Peter Horrocks reading: “Dear Peter, we are not standing still.” Members of the University and College Union have voted for sustained action to resist the closures as, in the words of one of my colleagues, it “will be the end of the Open University as we know it” if they go ahead. There is increasing alarm among academics that the OU’s progressive legacy, derived from Stuart Hall and others, is now under threat.

Geoff Andrews is staff tutor and senior lecturer in politics at the Open University. He is writing here in a personal capacity. His new book, The Shadow Man, has just been published by I. B. Tauris.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login