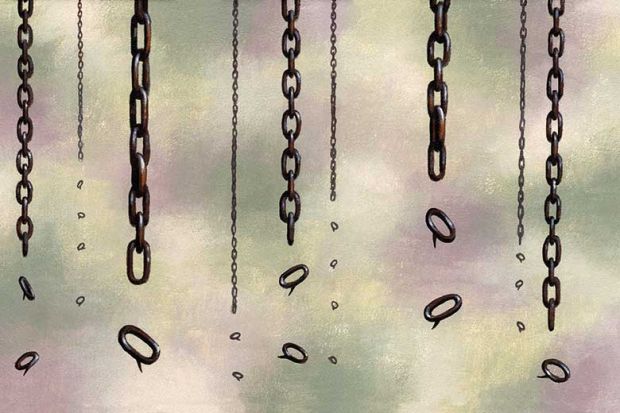

The current debates over reparations for slavery, and other historical acts that offend contemporary sensibilities, illustrate the extent to which universities are a soft touch when faced with such claims.

Almost any grievance can mobilise the liberal conscience of some section of the faculty or the student body. Institutional leaders tend to prioritise reputational risk – and a quiet life – over intellectual rigour. A few scholarships or a named centre are a small cost compared with the trouble that might be caused by pushing back. The University of Glasgow’s recently announced programme of “reparative justice”, after its investigation into its links with historical slavery, is unlikely to break the bank.

And last week, other universities were urged to set up a £100 million reparation fund.

A university should, though, be asking more critical questions. Who are we compensating for what? When might historical grievances be considered extinct? What are the consequences of one kind of compensation rather than another?

Slavery has never been a homogeneous social institution. Enslavement appears to have been a very common practice in ancient societies, but the treatment of slaves and their civic status varied a great deal. Even within the Atlantic trade, being a slave in Brazil was different from being a slave in the US – which was, in turn, different from being a slave in a British colony. Each had different legal status and economic opportunities.

Moreover, the slave markets of Africa were established long before the export trade developed. If the European traders exploited the labour they purchased more successfully than did their Arab and African partners, is this necessarily a reason to tax their descendants? Are the claims against the global North simply an indication that there are deeper pockets to pick?

We might also ask what distinguishes the Atlantic slave trade from, for example, the raids of 9th-century Vikings on Britain and Ireland, where large numbers of people were seized rather than bought. We might ask a similar question about the kidnapping of people from Ireland and southwest England for sale in North Africa by Barbary traders in the 16th and 17th centuries. Do these give rise to claims against the successor states by the descendants of those slaves, supposing always that we could identify them?

What about people who were expelled or fled historical persecution? Do the descendants of the Huguenots who escaped religious oppression in 17th-century France have a claim against the modern French state for their lost businesses? Are these claims extinguished simply because many of those refugees prospered in the more liberal environment of London? At some point, the tide of history has to wash away the scars on the sand.

Advocates of reparations might also be careful what they wish for. When this issue surfaced in the US in the early 2000s, a number of conservatives were very interested in supporting it. They had always seen equal opportunities legislation as an indefensible state intervention in the market. If black and Native American people were compensated, this would be a permanent buyout of their claims to special protection. It could be a way to liberate the market and roll back the state. In practice, they may also have thought that most of the money would find its way back to traditional white institutions, much as the carpetbaggers – economic opportunists from the North – exploited the post-Civil War settlement in the American South.

Applied to universities, some aspects of equal opportunities policies might come into question. If compensation payments had dealt with the historic economic disadvantages of a specific minority group, would it be justifiable to continue including that group alongside others who were still disadvantaged, for economic or other reasons? If we have compensated black descendants of slaves from the Caribbean, why would we give them the same social or legal protections as black people of free heritage arriving in the UK directly from Africa?

We certainly need a better popular understanding of the extent to which England, and Lowland Scotland, have long been multicultural and multi-ethnic societies – and of the ways in which patterns of advantage and disadvantage between those groups have emerged and been sustained. University historians have produced a substantial body of work that challenges the simple history of an ethnically and culturally homogeneous British nation, but this has not percolated into the wider culture. Similarly, as Jeremy Corbyn has recently observed, the public myths of the British nation have obscured the darker sides of empire. Would rewriting some of those national myths actually be a more appropriate form of compensation than cash?

This is a major challenge to the public engagement work of professional historians, and their media partners. How far will university historians be willing to risk the inevitable controversies from criticising both national myths and militant reactions? Will future historians just be writing peer-reviewed monographs for each other with the popular market left to myth-makers like Boris Johnson?

The reparations movement prompts important questions. While its own answers may be naive, the challenge to scholarship and public engagement deserves a serious, empirically grounded and rigorously argued response.

Robert Dingwall is a consulting sociologist. His most recent book is a translation of Howard S. Becker: Sociology and Music in the Chicago School, by Jean Peneff.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login