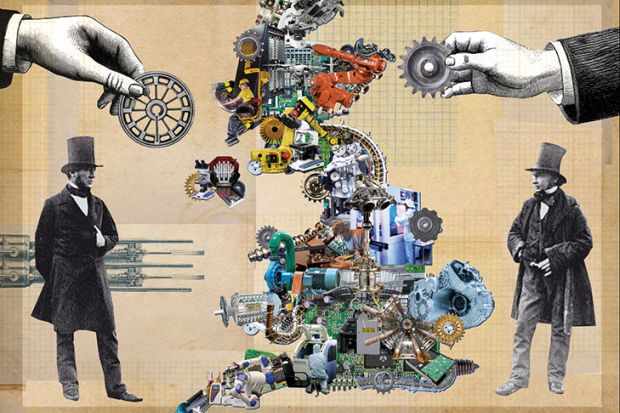

The UK emerged from the Second World War with a sizeable technological advantage over other nations, with vibrant research into computing, electronics, energy and aerospace engineering. However, that lead was quickly squandered by the inconsistent industrial strategies of subsequent governments.

The policy of the 1960s seemed to be one of benign neglect. British industries lacked government pressure or support to broaden and deepen skills and to modernise. By contrast, 1970s Labour governments were interventionist, famously “picking winners” among the industries deemed most promising and then reorganising them.

All that was swept away in the 1980s as the deregulation of the City of London focused political attention on financial services. Much of the UK’s hard-won intellectual property in more traditional physical industries was not properly protected or commercialised.

While New Labour returned to “picking winners”, it also saw risky financial services as the best bet for economic growth, leaving heavier and engineering-based industries still relatively unsupported. Major changes in the global marketplace also imposed acute input-cost and product-pricing pressures on these “making industries”, resulting in a loss of national competitive advantage.

We are now living through another moment of global paradigm shift, in socio-economic and geopolitical terms. The pace of this change is being accelerated by digital technologies, leading to what is being called a fourth industrial revolution.

Against this backdrop, the Conservative government’s latest industrial strategy, unveiled in January, presents the UK with a daunting but spectacular prospect. It involves embracing automation and thinking positively and imaginatively about how this can be combined with artificial intelligence and life science breakthroughs to advance not just the economy but the human condition.

The strategy diagnoses the UK’s weaknesses, but it is in essence a statement of intent. Strategic vision is useful only through tactical implementation, and we have not seen what shape this will take (assuming that the strategy is not derailed by an unlikely change of government in the forthcoming general election). That said, the “10 pillars” mentioned – including upgrading infrastructure, investing in science and cultivating world-leading sectors – pave the way for reorientation towards a more consistent, government-led industrial framework and specialism in sectors that differentiate the UK’s knowledge economy from international competitors.

The UK today is a world-leading science and technology economy. According to the Boston Consulting Group, 10 per cent of the UK’s gross domestic product comes from digital industries: a higher percentage than any other major global economy. We have seen through Elon Musk’s SpaceX that technology requires private backing to boost collaborations and achieve ambitious goals. The industrial strategy should recognise this and focus on relationships and partnerships as much as investment. UK universities, incubators and science parks play a role in advanced industry that would not have been considered in previous industrial strategies. They provide policy-leading research on everything from supercomputing, life sciences and energy to space engineering and satellite applications.

According to their response to the industrial strategy Green Paper, Russell Group universities have invested about £9 billion in major capital projects since 2012, delivering gross value added of £44.3 billion for the UK economy. The significance of such statistics should not be underestimated as they demonstrate the potential of an industry that relies on highly skilled workers.

The strong connection between the research base and manufacturing, as well as between disciplines on the research side, makes it easier to translate data into viable products. This means that the UK’s research excellence makes it highly competitive on the global stage. In a talk at Harwell last year, Sir John Bell, the leader of the government’s strategy for life sciences, said: “Real innovation in whatever discipline often occurs at the interface between areas of expertise. Multidisciplinary clusters become a huge cauldron for innovation.” This approach has become the new normal in high-tech industries and should be championed in government policy. At Harwell, scientists in the Science and Technology Facilities Council collaborate daily with many of the world’s largest research and development-focused corporations, for instance. These environments help to streamline supply chains, accommodating skilled labour, knowledge, resources and capital in one place.

Commercially viable products are best created by a combination of capital investment and scientific thinking. In the early 20th century, the Nobel prizewinner Ernest Rutherford credited austerity with sparking creativity, famously saying: “We’ve got no money, so we’ve got to think.” But there is a limit to how far that approach can be pushed. Fortunately, modern scientists are finally receiving the financial backing they need. The Green Paper makes a concrete pledge to invest an additional £4.7 billion in R&D by 2020, marking a heartening step up from the current 1.7 per cent of GDP invested. Knowledge-led research is valuable property, with more than £2 billion of national labs investment in Harwell alone, which is leveraged with intellectual property, product development and business incubators.

The UK research community is duty-bound to make the strategy’s ambitions a reality by showing the government – and ourselves – that we can be the new Victorians, building economic prosperity and national self-confidence on the back of technological progress. Infusing the industrial strategy with collaborative working cultures that prioritise the commercialisation of knowledge will go a long way to doing that, restoring the technological advantage that the UK enjoyed in 1945 – and ensuring that it isn’t squandered this time.

Angus Horner is a director of the Harwell Campus in Oxfordshire.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login