Hindsight may be a wonderful thing, but foresight is generally more useful.

With Joe Biden heading to the White House, one might argue that the predicted outcome in last week’s US election has come to pass – albeit without the blue landslide pollsters were forecasting.

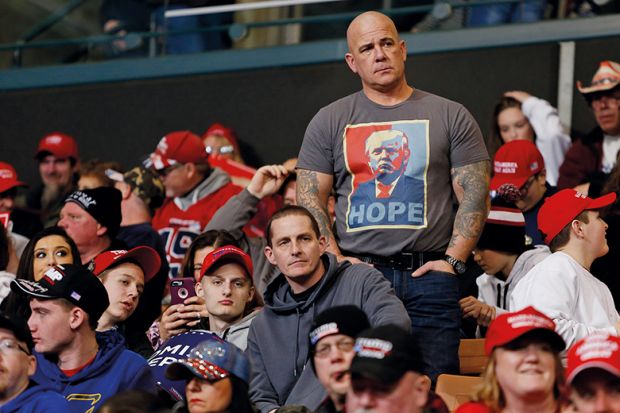

But for higher education, the fact that 71 million voters turned out for Donald Trump, a president who has consistently derided universities directly and indirectly with his assaults on truth and evidence, makes for a sobering moment regardless of the outcome.

Back in 2016, when the Brexit referendum and Trump’s election hit like an earthquake and its aftershock, universities in both the US and the UK did plenty of soul-searching, so alien were these choices from the values and principles that higher education espoused.

It seemed clear, in retrospect, that the years after the financial crash had disenfranchised great swathes of society on both sides of the Atlantic, and created social and economic fault lines that, in the view of the have-nots at least, cast universities firmly on one side of the divide.

Commitments reverberated that things had to change; that universities understood they were not reaching beyond their natural allies, and that they would find ways to do so.

Four years on, there is little evidence that this sphere of influence has significantly widened. Indeed, the social divisions seem in some ways to have got worse.

That this has happened despite a pandemic laying waste to our societies – and with science and research offering the only viable way out – makes it doubly perplexing.

At last week’s Times Higher Education Leadership and Management Summit, I interviewed Ron Daniels, president of Johns Hopkins University, which has had an exceptional impact during the Covid-19 crisis, not least through the work it has done with data to track the pandemic.

A website set up to provide the world with evidence to understand (and, therefore, tackle) the virus has had more than a billion visits, and it is instructive that this was not the result of any management master plan, but the work of a young researcher supported and amplified by a great institution.

In short, it was a university doing what universities do, and having a major impact on the world as a result.

For Daniels, though, the way to regain influence is not just through research, data or even the medical breakthroughs we all hope are coming, but by taking clear steps to stop simply replicating inequality. This, perhaps, is the only answer to the challenge posed by the Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel, when he describes universities as arbiters of opportunity in a world dominated by condescending, “credentialised elites”.

For elite institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Daniels argued, that means redoubling efforts on access and participation in particular. This would have an impact not only on society, but on the university too, since “when these children do come to these institutions and bring a set of experiences and perspectives [that] is different to the majority view, it is important that those views are welcomed and engaged with”.

While it may be easier for Johns Hopkins to do this with the help of a billionaire donor in Michael Bloomberg, a Biden presidency could also begin to address US higher education’s affordability crisis on a more systemic basis, Senate allowing. We report on this in our news pages.

The implications, though, spread far beyond the US or the specifics of this election.

The battle for hearts and minds is about the nature of the societies we live in, but also our ability to deal with the enormous challenges facing us in the years ahead.

It has been striking, during the pandemic, to see how collaboration in science and research has risen to the challenge, while no coherent global political response has been forthcoming.

In this context, the need for leadership from universities is even more pressing, but while this may seem obvious to anyone associated with one, it is not obvious to an awful lot of people.

If universities are to perform the central role we need for our collective future, efforts to change the narrative and win back trust across the whole of society must be reviewed and redoubled.

Because despite Biden’s win, populism that denounces evidence and truth seems to be a cockroach that can survive not only a pandemic, but even four years of President Trump.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login